Early life

Wayne Lo was born in Tainan, Taiwan. His father was a fighter pilot in the Taiwanese air force and his mother was a music teacher. Lo has a younger brother. The family immigrated to the U.S. in 1987, settling in Billings, Montana. His parents ran a restaurant business in Billings.

Lo attended Lewis and Clark Jr. High School and then Billings Central Catholic High School. Lo was a violinist and played in the Billings Symphony beginning in his freshman year of high school. He attended the Aspen Music Festival and studied under Dorothy Delay.

In 1991, Lo was accepted by Simon's Rock College of Bard in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and given the W.E.B. DuBois minority scholarship.

Shooting rampage

Lo did not adjust well to the liberal college environment of Simon's Rock. Lo held conservative views which were deemed racist, homophobic and anti-semitic by fellow students at the college. Lo steadily became more and more excluded by his fellow students.

On December 14, 1992, Lo carried out a shooting rampage. That morning he received an ammunition order that he had placed two days earlier. He then went to Pittsfield, MA and purchased an SKS at a gun shop that afternoon. Lo commenced shooting at around 10:30 pm. The victims:

-

Nacunan Saez - 37 - professor - shot dead

-

Galen Gibson - 18 - student - shot dead

-

Theresa Beavers - 42 - security guard - wounded

-

Thomas McElderry - 19 - student - wounded

-

Joshua Faber - 15 - student - wounded

-

Matthew David - 18 - student - wounded

Lo surrendered to the police after his rifle jammed and he called 911, informing them that he was the shooter. He was taken into custody without incident.

Trial and conviction

Although many statements were made prior to the trial regarding Lo's bigoted and racist views, he was never charged with a hate crime and the racist accusations were never substantiated during the month-long trial. Instead, the focus turned to his mental state at the time of the shootings as Lo's defense lawyers entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity.

Lo's psychiatrists testified he was suffering from schizophrenia while the prosecution expert psychiatrist witnesses merely attributed Lo's actions to his narcissistic personality disorder.

The jury sided with the prosecution and delivered a guilty verdict after three days of deliberation. Lo was found guilty on all 17 counts he was charged with and sentenced to two consecutive life without possibility of parole terms plus 19-20 years. He was immediately sent to prison on February 3, 1994.

Imprisonment

Lo spent 9 months at a maximum security facility at Walpole, MA and then transferred to MCI-Norfolk, a medium security prison where he remains today.

In 1998, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts rejected Lo's appeals.

In 1999, Gregory Gibson, the father of Galen Gibson, wrote and published Gone Boy -- A Walkabout (Kodansha America), a detailed book recounting the shooting and Gibson's search for answers in his son's death. The book spurred correspondence between Gibson and Lo. A New York Times article (NY Times April 12, 2000, front page) as well as a documentary film, Running Amok, by George Stefan Troller (German TV ZDF 2001) was made detailing this correspondence.

Popular culture

Lo wore a t-shirt with the name of a New York hardcore band Sick of it All during his shooting rampage. This spurred the band to issue press releases denouncing Lo's crime.

The rock band Weezer wrote a song about Lo. It appeared on their Deluxe Edition Blue Album (2004) disk 2, track 12. The song is called "Lullaby for Wayne". The song's chorus contains the lyrics Wayne you know it’s true/There's nothing you can do/So put them guns away/Who cares what’s wrong or right/So please give up the fight/Put them guns away.

Author Chuck Klosterman of "Sex, Drugs and Cocoa Puffs" (also Spin Magazine, ESPN, Esquire etc.) writes a passage in his book "Killing Yourself to Live" (pages 133-134) where Wayne Lo writes Chuck a letter from prison contemplating what questions may have been raised if Lo were arrested wearing a T-shirt with the hair-bands, "Poison" or "Warrant" instead of the shirt he had on, which sported the hardcore band, "Sick of It All."

Wikipedia.org

Questions Outweigh Answers In Shooting Spree at College

By Anthony DePalma - The New York Times

Monday, December 28, 1992

When his music changed, Wayne Lo changed, and in time two people lay dead, four others were wounded and a sheltering place had become a killing field.

As he sits in the Berkshire County House of Corrections in Massachusetts, charged with murder and assault with a deadly weapon in connection with a 20-minute rampage at Simon's Rock College in Great Barrington, Mass., only Mr. Lo knows what led him to turn away from the classical music he once loved and instead embrace the violent, discordant music known as hardcore, and a surly group of students who were equally entranced by it.

Only he knows how the same fingers that danced with such agility and emotion over the strings of a violin could, as the police say, have pressed the trigger of a semiautomatic assault rifle, shattering the campus silence and ripping through several lives. Searching for Why

Today, two weeks after the Dec. 14 shootings, the 300 teen-age students of Simon's Rock have gone home for the holidays. Workmen are replacing a shattered window and blood-stained carpet in the library. The college plans to reopen as scheduled on Jan. 24.

But questions still far outnumber answers about the reason such violence was committed, how the six victims were chosen and whether anything could have been done to prevent it.

Last week college officials spoke publicly for the first time about the shootings. They offered details about how tantalizingly close they had been to averting the rampage -- on the day of the shooting officials temporarily impounded a package sent to Mr. Lo that may have contained bullets -- but no answers to the haunting question why.

"I don't know what he was thinking and I don't know why he did what he did," said Bernard F. Rodgers Jr., vice president and dean of the college. "The temptation is almost irresistible to explain what happened by blaming someone, especially Wayne Lo. What's happening now is that he is being demonized in accounts that are presenting what essentially is a caricature of this boy."

The portrait of Mr. Lo that emerged after the shootings was of a tightly wound 18-year-old with a shaved head, an Asian-American whose calm exterior hid a secret Rambo. But as details about his life have come out, that simple sketch has had to be shaded by contradictory images. Scattered Details Of a Complex Life

As a high school student in Billings, Mont., Wayne Lo played first violin with the Billings Symphony Orchestra. He had a 3.56 grade-point average, starred on the basketball team and helped out in his parents' Chinese restaurant.

But for some reason this diligent student and gifted violinist became an angry, disaffected college sophomore who stopped taking violin lessons, only grunted at people he passed in the hallways and whom other students described as espousing racist views.

Several students agreed that his music, and the friends who went with it, offered the greatest insight into Wayne Lo.

His new circle of friends, the ones he increasingly spent time with over the past year, were known as the "hardcore group" because they listened to that type of music, a blend of heavy metal and punk rock. These students described as Mr. Lo's friends were on winter break and could not be reached, but others from the campus said they talked tough and sat apart from others.

"They were and are elitist," said Mishka Shubaly, a 15-year-old from Kingston, N.H., who said he knew Mr. Lo as a teammate on the Simon's Rock basketball team. "He held himself sort of above other people. A lot of it had to do with perfection."

Ian Lary, a 17-year-old freshman from Appleton, Me., said: "Certain people just felt uncomfortable with Wayne and his friends. People would come up to me and say we should get them off campus. A couple of his friends had fascist views."

Mr. Lary said Mr. Lo once wrote a class paper arguing that people with AIDS should be banished to Utah. Others said he was known to hate Jews, blacks and homosexuals, and to have contended that the Holocaust never happened.

Leila Kohler, who said she knew Mr. Lo from an English class and from spending time with him last spring while dating one of his best friends, also described him as holding his racist views.

But she also said Wayne Lo was known to play Vivaldi's "Four Seasons" from memory. "He was actually quite amazing when it came to playing the violin," she said. "It almost wiped away the fact that he was not a real human." Early Promise Of Excellence

Born in Tainan, Taiwan, to a career military officer and a music teacher, Mr. Lo showed all the signs of being a musical prodigy. When his father, Chia-Wei Lo, was transferred to a diplomatic post in Washington in 1981, the 7-year-old violinist played with the nearby Montgomery County Youth Orchestra.

The family returned to Taiwan in 1983 and then, in 1987, came back to the United States where the elder Mr. Lo, on the suggestion of a friend, opened the Great Wall restaurant in Billings. There, Wayne Lo's passion for the violin still burned, and at Billings Catholic Central High he did well in school and on the basketball court, despite his 5-foot, 4-inch, 135-pound frame.

In September 1991, Mr. Lo entered Simon's Rock College, an alternative school that in many ways seemed perfect for someone like him. The college was founded in 1966 in the belief that most high schools did not sufficiently challenge gifted students. It affiliated with Bard College in New York in 1979.

Simon's Rock attracts academically talented students as young as 14 years old who are ready to do college-level work years before they would have graduated from high school. About two-thirds of them spend two years at Simon's Rock, earning an associate's degree before transferring to other colleges with a wider variety of majors. Simon's Rock has a reputation for encouraging self discovery and comforting bright but young students as they come to terms with who they are.

But in this lively setting, Mr. Lo's life apparently somehow veered off course. Piecing together statements by college officials, students and the police produces an account of a fateful day two weeks ago for Wayne Lo. An Odd Package Arrives at Simon's Rock

On Monday morning, Dec. 14, exam week at Simon's Rock and one month to the day after Mr. Lo's 18th birthday, a United Parcel Service employee delivered a package for Mr. Lo. The receptionist who accepted it noticed it had come from a company in North Carolina called Classic Arms, and notified college officials.

Mr. Rodgers, the dean, concluded after an hour-long discussion with residence advisers that he had no authority to interfere with the delivery, but should try to find out what was inside. The package was returned to the mail room, where Mr. Lo picked it up.

The advisers for Mr. Lo's dormitory, Trinka Robinson and her husband, Floyd, went to the student's room and asked to see the contents of the package. Students said Mr. Lo had earlier argued with Mrs. Robinson because he had violated college policies about remaining in the dormitory during the Thanksgiving break. College officials said he had contracted chicken pox just before the holiday and did not fly home.

On this day, Mr. Lo initially refused Mrs. Robinson's request, but finally displayed what he said had been inside the package: ammunition magazines that appeared to be empty, a plastic rifle stock and an empty cartridge box. Mr. Lo said the cartridge box was a Christmas present for his father and the other items were his; he said he had a semiautomatic rifle at home in Billings that he used for target practice.

Mr. Lo then attended a previously scheduled meeting with Mr. Rodgers. They talked about the package and the college's rules prohibiting firearms on campus. Mr. Rodgers later said that Mr. Lo was "calm, coherent, logical and open." They discussed his plans to apply to transfer to a four-year college next fall.

Shortly after leaving Mr. Rodgers's office, Mr. Lo got into a taxi for the 20-mile ride north to Dave's Sporting Goods in Pittsfield, where, the police say, he bought an assault rifle, but no ammunition.

A Chinese-made SKS semiautomatic assault rifle can be bought for $150. Massachusetts has strict laws governing the sale of such weapons; a resident must obtain a firearms identification card from the local police and wait 30 days for a background check.

But a loophole allows an out-of-state buyer to bypass Massachusetts restrictions, put down cash on a counter and buy an assault rifle as easily as one can buy a personal computer.

Mr. Lo returned to campus in time to take a 3 P.M. exam. That night he attended a scheduled dormitory meeting with Floyd Robinson and other students. As Mr. Lo was in the meeting, college officials say, Trinka Robinson was warned by an anonymous telephone caller that Mr. Lo had threatened to kill her and her husband the next day.

She immediately called college officials, and as they discussed what to do, the shooting began. Shots Ring Out In the Night

When Bruce Beavers lost his job as a development counselor a year ago, his wife, Teresa, wanted to pitch in. She started a job as a security officer at Simon's Rock three months ago. On the night of Dec. 14, she was stationed at the main entrance to campus in the guard shack. It was cold and isolated, but it had a phone, and with the main road quiet and students busy studying, she and her husband had a chance to chat.

At about 10:20, Mrs. Beavers, who is 40, told her husband to hold on, because someone was approaching the shack. "There's a kid out here with a gun," she told him calmly. In the Berkshires, hunters are not unusual.

Mr. Beavers was at home in Lee, Mass., watching TV with the couple's four children. "Then she put down the phone," he recalled.

A few moments later, "I heard her say, "Oh my God, no!' " Mr. Beavers said. "Then I heard a crash, an explosion, and I heard her screaming."

The police say Mr. Lo had squeezed the assault rifle trigger twice, firing two bullets that passed through Mrs. Beavers's abdomen and smashed into the guard shack wall. She is now listed in serious but stable condition at Fairview Hospital in Great Barrington.

While his wife lay wounded, Mr. Beavers hung up and called the police.

According to police reports, Mr. Lo next turned on a Ford Festiva that had pulled up to the security shack. The driver was Nacunan Saez, a 37-year-old professor of Spanish from Argentina who spoke four languages and liked to take 50-mile bicycle rides. Professor Saez had never taught Mr. Lo. The gunman pulled the trigger again and a bullet hit Professor Saez in the side of the head, the police say. The teacher drove his car off the road, into the snow, and died there.

The police say the gunman then headed toward the Simon's Rock library, where students who had heard the first shots were wondering what had happened.

There, they say, he fatally shot Galen Gibson, an 18-year-old apprentice poet and lover of theater from Gloucester, Mass., and wounded Thomas McElderry, 19, of New York Mills, Minn..

His next destination was a dormitory, where Joshua A. Faber, 15, of Pittsford, N.Y., had been watching Monday Night Football in a television room in the basement.

Mr. Faber, in a telephone interview from his home, said he did not think Mr. Lo planned to shoot him. He knew Mr. Lo only slightly, he said, and had on occasion played football with him after class.

When he and some friends came upstairs to the lobby at halftime, they were told about the gunfire.

"At first we dismissed it as a prank," Mr. Faber said.

But as Mr. Faber and another student, Matthew Lee David of Montclair, N.J., stood in the lobby, the police say, they were in Mr. Lo's line of fire.

"Suddenly I felt an explosion and I realized I had been shot," Mr. Faber said. "I thought I'd better get away from the area as quickly as possible. I hopped up the steps and a friend helped me into the residence director's room."

He was shot through both thighs and his left calf. His friends wrapped a tourniquet around his right thigh and applied pressure to the left while they waited for an ambulance. Mr. David was also wounded. Questions Asked But Not Answered

It all took less than 20 minutes. When the shooting stopped, the police reports say, Mr. Lo went to the student union building and contacted the police.

He then laid down his rifle, put up his hands and walked out into the night, where police officers were waiting for him.

The next morning he was brought before a judge at Great Barrington District Court to hear the charges against him read. He wore a sweatshirt embellished with four words that are the name of a hardcore band whose songs had replaced Vivaldi's compositions in Mr. Lo's life. The name of the band is Sick of It All.

Since being taken into police custody, Mr. Lo has said nothing publicly about the shootings. He is being held without bail while a grand jury reviews the charges against him.

The district attorney's office will not comment, and neither will Mr. Lo's lawyer, Janet Kenton-Walker of Amherst, Mass. Distraught college officials have found no note or other explanation for the horror and are left to anguish over what they could have done differently.

In Billings, the young man's mother, Lin-Lin Lo, struggles to understand why the music changed.

"These things that happened I still cannot figure out," she said by telephone Saturday. "Wayne is a fine boy, a lovely boy. He cares about family, he cares about friends. I really don't understand what happened."

Docket No.:

97-P-801

Parties: RLI INSURANCE COMPANY vs.

SIMON'S ROCK EARLY COLLEGE & others.(1)

County: Essex.

Dates: February 7, 2001. - March 22,

2002.

Present: Jacobs, Duffly, & Cypher, JJ.

Contract, Insurance. Insurance, General

liability insurance, Excess liability

insurance, Construction of policy, Coverage.

Negligence, College. Words, "Occurrence,"

"Cause."

Civil action commenced in the Superior Court Department on July 29, 1994.

The case was heard by Peter F. Brady, J., on motions for summary judgment.

Eugene G. Coombs, Jr., for the plaintiff.

Bruce G. von Rosenvinge for American Alliance Insurance Company.

DUFFLY, J. This case involves a dispute between the primary and excess liability insurers of Simon's Rock Early College a/k/a Simon's Rock College of Bard (college) as to the amount of coverage available under the college's primary policy for claims arising from a 1992 shooting rampage by a student of the college. On cross motions for summary judgment, a judge of the Superior Court allowed the motion of the primary insurer, American Alliance Insurance Company (American), denied RLI Insurance Company's (RLI's) motion, and made a declaration that all claims arising from the shooting rampage arose out of a single occurrence; that American's policy with respect to the underlying claims would be exhausted upon payment of its $1 million per occurrence limit; and that RLI's obligation to pay would begin upon exhaustion of American's per occurrence limit. The effect of the judgment was to increase RLI's exposure under its excess policy of insurance. RLI appealed. The crux of this dispute is whether there were multiple "occurrences" under the American policy, requiring American to pay its aggregate policy limit of $3 million. We affirm the judgment, but because our analysis differs from that of the Superior Court judge, we set forth our reasoning following a summary of the undisputed facts.

Facts.

On December 14, 1992, Wayne Lo, a student at the college, went on a shooting spree that lasted eighteen minutes, spanned approximately a quarter of a mile, and resulted in the killing of two and the injuring of four individuals.

The events of the day began at approximately 10:00 A.M., when a receptionist at the college took delivery of a package addressed to Lo that bore the return address of an arms store. She advised certain of the college's residence directors of the package, and they brought it with them to a regularly scheduled meeting with Bernard Rodgers, a dean of the college.

There was discussion of the package at the meeting, which lasted about an hour and included discussion of other business. Concern was expressed over the return address, "Classic Arms" in North Carolina, and that the package might contain a weapon in violation of the college policy prohibiting firearms, weapons, and explosives on college property.

Dean Rodgers and the residence directors decided to allow the package to be delivered to Lo, and that once received by him a prompt inquiry would be undertaken to determine the package contents. Following the meeting, the package was returned to the package room, where it was picked up by Lo a short time later.

Katherine "Trinka" Robinson, one of the residence directors, learned that Lo had picked up the package and followed him back to his dormitory room, where he opened the door to her knock. She saw the unopened package and requested that Lo show her its contents. Lo refused, relying on college policy requiring that permission to search be obtained from the associate dean of students, and that the search be in the presence of at least one other college staff member. Robinson left and called Dean Rodgers from her apartment. He directed her to return to Lo's room to determine the package contents.

Accompanied by her husband, Floyd Robinson, also a residence director, Katherine Robinson returned to Lo's room and, when he opened the door, observed three or four apparently empty black plastic magazines, a black plastic rifle stock, and an empty metallic army surplus cartridge box, but no ammunition or gun. Lo explained that the cartridge box was a gift for his father, and the other items were for his own use at home in Montana, where he had a semiautomatic rifle that he used for target practice.

Lo gave this same explanation to Dean Rodgers who, after Katherine Robinson called to describe what she had observed in Lo's room, requested that Lo come immediately to the dean's office. When Lo arrived at the dean's office with the items, he appeared to be calm and was not defensive as he expressed to the dean his understanding of the college's policy that no firearms were permitted on campus.

Later that day, Lo traveled by taxi to a Pittsfield sporting goods store where he purchased an assault rifle. That evening, sometime after 9:00 P.M., as Lo was attending a house council meeting with Floyd Robinson and other students, Katherine Robinson received a telephone call at her home. The caller, who refused at the time to identify himself, stated that Lo had a gun and live ammunition and was going to kill the members of the Robinson family and others the following night. The caller was another student with whom Lo had just had dinner, during which Lo performed a mock "Last Supper" and indicated he was going to kill. The Robinsons contacted the college provost, Ba Win, and at his urging went with their children to the Win home. There they called Dean Rodgers to convey a plan to locate Lo and search his room for weapons. As they spoke, they heard shots being fired nearby that turned out to be the opening salvo in the unfolding tragedy.

Some of the individuals who were wounded, their families, and families of the deceased brought suit against the college, in essence alleging that it was negligent in failing to prevent Lo from engaging in the wrongful acts that resulted in their damages. RLI filed a complaint seeking a declaration that the coverage available for all of the underlying tort clams under American's policy of insurance was the aggregate limit of $3 million. American's counterclaim sought a declaration that coverage under its policy would be exhausted upon the payment of its per occurrence limit of $1 million.

Discussion.

The parties contend that in Massachusetts, as in the majority of jurisdictions having decided the issue, the number of occurrences is determined by the "cause" theory, which construes occurrence "by reference to the cause or causes of the injury or damage rather than the number of claims." Doria v. Insurance Co. of N. America, 210 N.J. Super. 67, 73-74 (1986) (citing cases; Annot., 55 A.L.R.2d 1300, 1303 [1957]; and 15A Couch on Insurance § 56.21 [2d ed. 1983]).

Although aspects of the cause theory do appear to have been adopted by our courts, this does not answer the question, as evidenced by the parties' disagreement as to what constitutes the cause in this case: RLI argues that the cause of the injuries here was Lo's shooting, whereas American takes the position that the conduct of the college and its employees in allegedly failing to prevent the shooting was the cause. We therefore precede our discussion of the ultimate issue -- the number of occurrences -- with a discussion of what determines the "cause" of injury in this context. We emphasize that when we speak in this opinion about cause of injury we are referring to that cause or occurrence that gives rise to insurance coverage. This may or may not be the same as the cause or causes of injury for purposes of tort liability.(2)

We conclude that when the issue is the number of occurrences, we must look to the "cause" of the injury by reference to the conduct of the insured for which coverage is afforded, and that "cause" and "occurrence" are indistinguishable for purposes of this analysis.(3) Our view is supported both by the terms of the relevant policy of insurance and by decisional law.

American's policy provides general liability coverage for "those sums that the Insured becomes legally obligated to pay as damages because of 'bodily injury' . . . caused by an 'occurrence,'" with occurrence defined as an "accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same general harmful conditions."(4) Specifically excluded is coverage for bodily injury that is "expected or intended from the standpoint of the Insured."

In this case, where the underlying claims against the school and its employees are for negligence, it is their allegedly negligent acts or omissions in failing to prevent Lo from using his gun that constitute the occurrence for purposes of determining general liability coverage provided by American's policy. See, e.g., Washoe County v. Transcontinental Ins. Co., 110 Nev. 798, 804 (1994), a case where the employee of a private day care facility licensed by the county allegedly abused children at the facility. The plaintiffs in the underlying action alleged that the county was negligent in the process of licensing the facility. The court held that, for purposes of determining the county's insurance coverage, the county's negligence was the cause of the children's injuries. "[E]ven though the action of the individual wrongdoer[] [is] the most direct cause[] of harm for the victims . . . the actions of the individual wrongdoer[] taken alone are not the basis of liability . . . . Instead, liability . . . is premised on the [county's] negligence in performing a duty, which permitted the intervening conduct of [the wrongdoer] who actively caused the victims' harm."

A similar analysis obtained in Worcester Ins. Co. v. Fells Acres Day Sch., Inc., 408 Mass. 393 (1990), a case involving policies of insurance containing definitions of "occurrence" substantially identical to the one at issue here.(5),(6) As in Washoe County, supra, the case in Fells Acres involved insurance coverage related to the abuse of children at a day care center by the facility's employees. In determining that there could be insurance coverage for acts of negligence by the school and its employees, the Supreme Judicial Court relied on "conventional negligence theory," 408 Mass. at 410, focusing on the insureds' negligence in the hiring, retention, and supervision of the employees who committed the assaults. Id. at 407-411.(7)

Thus, in Fells Acres, as in Washoe County, and, as we conclude, in the matter at hand, it is an insured's actions or failures to act (here the alleged negligence) and not the deliberate acts of a wrongdoer that constitute the "cause" of the victims' injuries. See also Aylward, Multiple "Occurrences" -- A Divisive Issue, 5 Coverage 39, 40 (Jan./Feb. 1995) ("where the insured's conduct was remote to the immediate cause of the plaintiff's injuries, as in products liability cases or theories of liability based on negligent training, supervision or inspection, the direct cause of injury may have little relevance to the 'cause' for purposes of ascertaining the number of 'occurrences'").

As Judge Weinstein observed in Uniroyal Inc. v. Home Ins. Co., 707 F. Supp. 1368, 1383 (E.D.N.Y. 1988),(8) "Since the policy was intended to insure [the college] for its liabilities, the occurrence should be an event over which [the college] had some control. Otherwise, with the covered risks out of the insured's hands and coverage for losses determined by the acts of the unfettered [shooter], the insurer would have no basis for setting premiums ex ante and the insurance contract would be illusory." Other jurisdictions have similarly held that "[i]n interpreting coverage for . . . entities [such as the college here] under the 'causal' approach, 'occurrence' should be defined in such a way as to give meaning to the entity's connection to liability." Washoe County v. Transcontinental Ins. Co., 110 Nev. at 805. Cf. Windt, Insurance Claims and Disputes § 11.3, at 298 (4th ed. 2001) ("whether an accident is present should be considered from the point of view of the insured").

In addition to determining whether conduct of an insured constitutes an insured risk under a general liability insurance policy, we also look to such conduct to answer the question whether there was a single occurrence or multiple occurrences for purposes of determining "per occurrence" liability of an insurer.(9) We therefore look to the alleged acts of the insured college and its employees in failing to prevent Lo from engaging in the shooting spree as determining the number of occurrences, and not to the acts of Lo himself. By way of illustration, we turn to Travelers Indem. Co. v. Olive's Sporting Goods, Inc., 297 Ark. 516 (1989), a case involving facts similar to those before us. There, the insured store allegedly sold a pistol and shotgun to one Wayne Crossley, who then used the weapons to shoot a policeman and kill and wound several others, before committing suicide. The court focused on the insured in deciding the issue of the number of occurrences, and determined that the occurrence was the sale of weapons, noting that "[t]o decide that each of the injuries required separate coverage under the policy would in effect put a no-limit policy into effect." Id. at 522. Compare State Farm Lloyds, Inc. v. Williams, 960 S.W.2d 781, 785 (Tex. Ct. App. 1997) (where insured shooter was covered by his homeowner's policy, "the insured's liability arose out of the shootings"). Thus, it is with reference to the conduct of the college and its employees that we now determine the question of the number of occurrences under American's policy of insurance.

As we observed earlier in this opinion, occurrence is defined in American's policy as an "accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same general harmful conditions." "The term 'occurrence' that appears in the policies was used by the insurance industry instead of the term 'accident' beginning in the 1960's. The term 'occurrence' was adopted 'to dispel any existing notion that [coverage] was limited to sudden happenings.'" Worcester Ins. Co. v. Fells Acres Day Sch., Inc., 408 Mass. at 416. The unambiguous language of American's policy, considered in the light of this historical backdrop, clearly contemplates the possibility that multiple acts taking place over a space of time may contribute to a single occurrence for purposes of coverage. We do not read Fells Acres as requiring the conclusion that the acts of the college and its employees constituted multiple occurrences. The court in that case, noting that there were allegations of "numerous discrete acts of . . . negligence . . . and breach of duty" resulting in, or that failed to prevent, the abuse of the children over a lengthy period of time by multiple defendants in various locations, held that "[t]hese allegations preclude the possibility that there was but a 'single, ongoing cause' of the injuries alleged." Id. at 417. Nor does Slater v. United States Fid. & Guar. Co., 379 Mass. 801 (1980), require a different result.(10)

There is nothing in the agreed upon facts to suggest that any of the acts or omissions on the part of the insured defendants was a "discrete" act of liability so separated by time and location as to warrant the conclusion that each such act resulted in Lo having access to a weapon that he then used to shoot several people. Unlike in Fells Acres, it cannot be said that each alleged act of negligence resulted in a discrete injury. Rather, all the negligent acts combined to result in Lo's eighteen-minute rampage. Cf. Appalachian Ins. Co. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 676 F.2d 56, 59, 61 (3d Cir. 1982) (primary issue was when occurrence took place, but court also noted that where policy defined "occurrence" as an "accident or happening or event or a continuous or repeated exposure to conditions which unexpectedly and unintentionally results in . . . injury," the insured's policy contemplated "multiple and disparate impacts on individuals and that injuries may extend over a period of time," and held that discriminatory employment policy constituted a single occurrence). Although several events have been described as leading to Lo's shooting spree (e.g., the failure to search Lo's room, to confiscate his weapons parts, to call Lo's parents, to call the police), these facts do not describe separate occurrences, but rather constitute evidence of an arguably inadequate policy of security and student supervision that may have contributed to Lo's ultimate access to a murder weapon. It is this alleged failure or inadequacy of the college's policy that forms the basis of the insureds' liability here, and constitutes a single occurrence for insurance coverage purposes.(11)

The cases relied on by RLI, see, e.g., American Indem. Co. v. McQuaig, 435 So. 2d 414 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1983); State Farm Lloyds, Inc. v. Williams, 960 S.W.2d at 784-785, are inapposite. In these cases, the multiple, discrete acts of an insured, whose shooting of several people was separated (albeit briefly) by time was found to constitute more than one occurrence. There, unlike in the instant case, the shootings were the "cause" because conducted by the insured.(12) The conduct of the gunman, and not any negligent act or failed policy of supervision, was the relevant conduct in determining the number of occurrences within the meaning of the policy.

We conclude that the underlying claims in this case arose from a single occurrence under the terms of American's policy, limiting American's liability to $1 million.

Judgment affirmed.

*****

footnotes

(1) Bard College; American Alliance Insurance Company; Bernard Rodgers; Ba Win; Judith Win; Floyd Robinson; Trinka Robinson; Gregory Gibson, individually and as he is administrator of the estate of Galen Gibson; Anne Marie Crotty; James E. Farrell, Jr., administrator of the estate of Nacunan L. Saez; Donald N. David, individually and as he is guardian of Matthew David; Matthew David; and Evalyn David.

(2) That the distinction is important is particularly evident in this discussion about the number of occurrences. Confusion can arise when, as is often the case in opinions discussing the issue, the language of tort liability is called upon to inform the language of insurance risk coverage. In this case, for example, RLI's position -- that the number of occurrences is determined by reference to the immediate cause of the victim's injuries, i.e., Lo's shooting -- is based upon the assumption that "cause of injury" is that cause which, in a tort liability sense, is the immediate cause of harm, albeit not the exclusive proximate cause. This ignores the fact that the issue to be determined is not liability, but the contractual obligation of an insurer to an insured. See discussion, infra.

(3) "Cause" and "occurrence" in this context are not to be confused with the "trigger of coverage" issue, which identifies the time of the occurrence for purposes of determining whether a claim falls within the policy period of a particular contract of insurance. "[I]t is important to distinguish concepts of cause and effect as they relate to the related purposes of determining which policy applies and how many policy limits are triggered. A liability policy is not 'triggered' by the happening of an 'occurrence.' Rather, it is triggered at the point in time when an 'occurrence' results in bodily injury or property damage." Aylward, Multiple "Occurrences" -- A Divisive Issue, 5 Coverage 39 (Jan./Feb. 1995).

(4) The American policy provides, in pertinent part:

"COVERAGE A. BODILY INJURY AND PROPERTY DAMAGE LIABILITY

"1. Insuring Agreement

"a. We will pay those sums that the insured becomes legally obligated to pay as damages because of 'bodily injury' or 'property damage' . . . . But

(1) the amount we will pay for damages is limited as described in Limits of Insurance.

. . .

"b. This insurance applies to 'bodily injury' and 'property damage' only if:

(1) the 'bodily injury' or 'property damage' is caused by an 'occurrence' that takes place in the 'coverage territory.'"

(5) The provision in the special multi-peril policy issued by Worcester Insurance Company provided coverage for an "occurrence" defined as "an accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to conditions, which results in bodily injury . . . neither expected nor intended from the standpoint of the insured," Worcester Ins. Co. v. Fells Acres Day Sch., Inc., 408 Mass. at 398 n.6 (emphasis omitted), and is comparable to the language in American's policy.

(6) We disagree with RLI's contention that the term "occurrence" as defined by the American policy is ambiguous when applied to the present circumstances. We therefore need not decide whether the policy provisions must be construed against American, Hakim v. Massachusetts Insurers' Insolvency Fund, 424 Mass. 275, 281 (1997), or whether the rule of insurance contract interpretation construing any ambiguity against the insurer and in favor of the insured does not apply to cases involving a dispute between insurance companies. Union Carbide Corp. v. Travelers Indem. Co., 399 F. Supp. 12, 15-16 (W.D. Pa. 1975). Hatch v. First Am. Title Ins. Co., 895 F. Supp. 10, 13 (D. Mass. 1995), quoting from Falmouth Natl. Bank v. Ticor Title Ins. Co., 920 F.2d 1058, 1062 (1st Cir. 1990) ("[t]he rationale behind interpreting ambiguities against the insurer would not seem to apply as strongly when the transaction is between two parties of equal sophistication and equal bargaining power").

(7) The legal analysis in Fells Acres was complicated by the fact that, unlike in Washoe County, or the matter before us, the individual assailants were also insureds, as they were corporate officers and stockholders of the school, as well as staff members. The court thus had to distinguish between the actions of the insureds as assailants (herein, wrongdoers), and the allegedly negligent actions of the insureds in their other capacities, excluding their own acts of abuse. The court determined that there was no insurance coverage for the wrongdoers' assaults on the victims, holding that, as matter of law, none of the claims of sexual assault of the minor plaintiffs was covered because the children's injuries necessarily were expected or intended from the point of view of the insured/wrongdoer (and therefore did not result from an accident or occurrence within the meaning of the policy). Worcester Ins. Co. v. Fells Acres Day Sch., Inc., 408 Mass. at 399-403.

(8) In Uniroyal Inc. v. Home Ins. Co., supra at 1382-1383, the court determined that each spraying of "Agent Orange" did not constitute a separate occurrence, holding that the single occurrence was plaintiff insured's delivery of herbicides to the military: "The delivery was the last act performed by Uniroyal in which it exercised any control over the herbicides." Id. at 1383.

(9) This is a question that is distinct from the question of the harm or injury giving rise to, or triggering, the coverage. See note 3, supra.

(10) The insured orthodontist in Slater had a property insurance policy that specifically covered losses of money "for an amount not exceeding $250 in any one occurrence." 379 Mass. at 802. Over a period of two years, the doctor's receptionist embezzled a total of $9,000, with no one theft exceeding $250. The court concluded that each act of embezzlement constituted a separate occurrence. Because "occurrence" was not defined in that policy, the term was construed against the insurer. Id. at 802-804. In addition to the distinguishing fact that in American's policy the term "occurrence" is defined, we further note that the insurance policy at issue in Slater was not a policy of general liability coverage for accidents resulting in third party injury.

(11) We do not intend to preclude the possibility that multiple occurrences might be found to exist in other cases involving a failure to supervise or to implement a security policy. See, e.g., Worcester Ins. Co. v. Fells Acres Day Sch., Inc., 408 Mass. at 417 (multiple occurrences in light of time, space, and the number of defendants and acts of abuse). Cf. Slater v. United States Fid. & Guar. Co., 379 Mass. at 806-807 (noting that multiple occurrences have been found "when the cause is interrupted, either by an independent cause, or by the actor regaining control over the causing factor"). We think that the issue must in each instance be determined by the facts of a given case.

(12) In State Farm Lloyds,

Inc. v. Williams, supra at 785, the court

noted that "the insured's liability arose

out of the shootings . . . . [The victims]

were not injured by a single shot. Rather,

their injuries resulted from two separate

acts. Because each 'act' independently gave

rise to liability, we conclude the shootings

constituted two separate occurrences under

the policy." In McQuaig, the insured's

shooting of two sheriffs, firing at three

separate intervals separated by brief spans

of time, was held to constitute three

separate occurrences. American Indem. Co. v.

McQuaig, supra at 415.

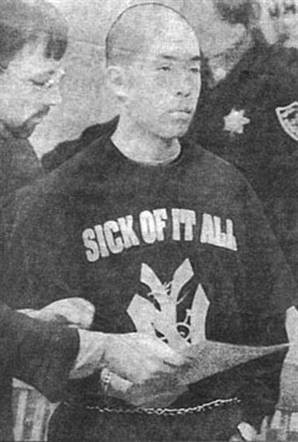

Wayne Lo appears in court the day after he shot six

people

on his college campus.