Maestas sentenced to die by lethal injection for 2004 murder

By Linda Thomson - Deseret Morning News

Thursday, Feb. 7, 2008

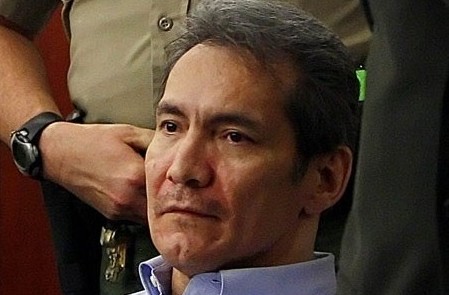

Convicted murderer Floyd Eugene Maestas was sentenced Wednesday to die by lethal injection despite a flurry of last-minute efforts by defense attorneys to change the outcome of the hearing.

Maestas, 52, was previously convicted by a jury of killing Donna Lou Bott, 72, after breaking into her Salt Lake home Sept. 28, 2004, and beating, choking, stabbing and then stomping the woman, which ruptured the aorta in her heart.

Maestas has continually denied committing the crime and had no comment Wednesday.

Third District Judge Paul Maughan imposed the death sentence to be carried out within 30-60 days, but then stayed the execution order because he said such sentences are automatically appealed to the Utah Supreme Court.

The judge denied two motions by the defense team to give Maestas a new penalty phase trial for his capital murder conviction and also to set aside the verdict of death because of what the lawyers described as Maestas' limited mental capacities and his inability to properly advise his defense attorneys.

Defense attorney Denise Porter challenged the way a question from a juror had been handled. The juror had asked whether the Board of Pardons could overrule a sentence of life in prison without parole and still offer parole. However, Maughan said that motion was too late and that the jurors had been directed to examine jury instructions that spelled out which of the two verdicts they could render.

Then defense attorney David Mack objected to the judge's ruling that Maestas had the legal right to make decisions regarding his defense. Maestas last week vehemently opposed his attorneys' plans to present evidence of his hardscrabble childhood, involving sexual, physical and substance abuse.

That evidence presumably would have shone some embarrassing light on Maestas' family, and he insisted he would not involve his family in the court proceedings, even if that meant that would put him at a disadvantage.

Mack argued that Maestas does not have the intellectual functioning to be able to make those decisions. He said it was ironic that a room filled with highly educated people put their creative energies toward seeing that a "damaged, morally disadvantaged" person was sent to his death.

Mack also said it was "freakish" that the court ordered the defense team to take orders from Maestas when he was the least capable person to understand or help with such intricate legal matters that had such high stakes. Mack said the jury ended up with an "unreliable verdict" and that Maestas' 8th Amendment rights, which forbid cruel and unusual punishment, had been violated.

Prosecutor Kent Morgan disagreed with that motion and said that Maestas had received a fair trial and had the right to direct his own defense. Morgan said what is freakish is that someone would try to essentially get a plea bargain after a jury had gone through a trial and come up with a guilty verdict and a recommendation for the death penalty.

The judge denied that motion as well. Maughan said that Maestas had been found to be mentally competent to stand trial and help in his own defense and was permitted by law to decide what evidence would be presented on his behalf.

"He may not have the full range of mental capabilities, but he is certainly competent to make that decision," the judge said.

The judge said the defense attorneys had presented no new evidence, only an "emotional appeal."

Robin Crane, a friend of Maestas since junior high school, wept as she described how Maestas had "given up" and did not believe he could get a just trial because of the plea deals given to two co-defendants who were with him the night Bott was killed and who testified against him.

"I've known him for 30 years; he's not a monster," she said. "He's a victim of his circumstances."

She said he never got a chance to do well in school, was put in "special classes" for the less intelligent students mainly because he spoke Spanish and has had a rough life. Crane said Maestas was guilty of a lot of bad things — "smaller stuff" such as burglary — but he would not plead guilty to a crime such as murder because he didn't do it.

Asked about Donna Bott's grieving family, Crane said she was sorry for their loss and hoped that the real culprit would feel guilty and come forward. "It's not likely, but we can pray for it."

Some background on Maestas

October 23, 2004

Floyd Maestas' fingerprints were found in her home. His DNA was found in her body.

But while Maestas may have been responsible for the stabbing, beating, raping and strangling of 75-year-old Donna Lou Bott, it took more than one man to kill her.

It took an entire system.

Over the past 30 years — through at least a half-dozen similar attacks against elderly women — charging decisions, plea negotiations and parole board determinations have ensured Maestas has never been convicted of a single violent crime. As a result, he never spent much time behind bars.

The maddening story begins no later than 1974, as Bruce Hansen walked passed the darkened home of the aunt who raised him.

"I usually visited her on my way home, but on that night I didn't," he says. "I still can't forgive myself for that."

Inside, Maestas was beating and raping 64-year-old Donna Jensen.

"The doctors had to sew one of her nipples back on — that's how bad it was," Hansen recalls.

Maestas, then 17 years old, was convicted of burglary. He was paroled after serving 18 months.

Three months after his release, he was arrested again.

Jerrilynn Comollo still sobs when she thinks about cleaning Maestas' blood from underneath her grandmother's fingernails. "She had fought so hard that all that blood was way down into the quick," Comollo recalls.

Alinda Ross Robbins McLean's nails were the least of the 79-year-old woman's concerns: Over the course of several hours on the evening of Oct. 13, 1976, she was repeatedly raped and savagely beaten. And before Maestas left her home, he lifted a broken lamp from the floor and told the twice-widowed woman that he was going to use it to gouge out one of her eyes.

And then he did just that.

While she cleaned her grandmother's hands — the only thing Comollo could think to do at the moment — the old woman wondered aloud why she had been chosen for such punishment.

"She just kept saying, over and over, 'I can't understand why anyone would do this to me.'"

There was, of course, no answer for that poor, beautiful, old woman. But there was a promise that should have been made. A promise that should have been kept.

A promise that wasn't: Maestas served six years for the attack on McLean. And he spent the following decade in and out of prison on a slew of parole violations — most of which, his family members recall, had something to do with elderly women.

In the fall of 1989, prosecutors were eyeing Maestas in at least three new burglaries. In two, the elderly victims were physically beaten and sexually assaulted.

But officials chose to prosecute Maestas on a third case: A burglary in which Maestas was confronted by three elderly Greek sisters — who had come home from church together to make some Baklava — and chased out of their home before he could attack.

Convicted of theft, burglary and being a habitual criminal, Maestas was sentenced to one to 15 years in prison.

The other cases were set aside. One was dismissed, the other never filed.

Loene Nelson, now 69 years old, is still not sure why her case was ignored.

"At the time, a detective showed me his rap sheet and said, 'Listen, this is all this guy needs to be put away forever," Nelson says. "I believed him."

Nine years later, Maestas was back on the street. Once again, he repeatedly violated his parole. In April, 2000, he was convicted of burglary — one of few convictions on Maestas' lengthy criminal record that does not involve an elderly female victim — and sentenced to a one-to-5-year prison term.

He was released from prison on Sept. 7 — nine months before the full five years and without supervision, said parole board chairman Mike Sibbett.

Three weeks later, Bott was dead.

Her badly beaten body lay in the bedroom of her home for three days before police — acting on the concerns of neighbors — entered her home. Next to her body, they found a pair of her underwear.

An autopsy determined Bott's face had been slashed while she was still alive. She was strangled and her teeth were fractured. And she had been raped.

Maestas left a mountain of physical evidence in his wake. And that is all well and good for prosecutors, who appear poised to seek the death penalty in Bott's murder.

They're now making the promise they should have made long ago: If Maestas doesn't die of lethal injection, he'll die in prison.

But it's too late for Jensen. Too late for McLean. Too late for Nelson.

The failure to make the promise became the lifeblood of a serial rapist. And the failure to keep it resulted in the death of Donna Lou Bott.