|

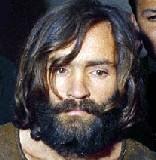

People v. Manson

61 Cal. App. 3d 102

Crim. Nos. 22239, 24376.

Court of Appeals of California, Second Appellate

District, Division One.

August 13, 1976.

THE PEOPLE, Plaintiff and Respondent,

v.

CHARLES MANSON et al., Defendants and Appellants

Opinion by Vogel, J., with Thompson, J.,

concurring. Separate concurring and dissenting opinion by Wood, P. J.

COUNSEL

Albert D. Silverman, under appointment by the Court

of Appeal, Daye Shinn, Maxwell S. Keith, Kanarek & Berlin, Irving A.

Kanarek and Roger Hanson for Defendants and Appellants.

Evelle J. Younger, Attorney General, Jack R.

Winkler, Chief Assistant Attorney General, S. Clark Moore, Assistant

Attorney General, Norman H. Sokolow and Howard J. Schwab, Deputy

Attorneys General, for Plaintiff and Respondent.

OPINION

VOGEL, J.

Facts

Appellants Charles Manson, Patricia Krenwinkel, and

Susan Atkins fn. 1 were indicted by a grand jury on seven counts of

murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder. Appellant Leslie

Van Houten was indicted in two of the same seven counts of murder and

in the conspiracy count.

A jury found all appellants guilty as charged and

further found the murders to be of the first degree. After the penalty

phase the same jury [61 Cal. App. 3d 124] imposed death sentences upon

all appellants. The resulting judgment was appealed directly to the

Supreme Court (Pen. Code, § 1239, subd. (b)). While this case was

pending that court decided People v. Anderson (1972) 6 Cal. 3d 628

[100 Cal.Rptr. 152, 493 P.2d 880], cert. den., 406 U.S. 958 [32

L.Ed.2d 344, 92 S.Ct. 2060], invalidating the death penalty. On that

basis, these appeals were transferred to this court for determination.

The Homicides

The events giving rise to the charges contained in

the indictment are two successive multiple homicides occurring in the

City of Los Angeles during August of 1969. fn. 2 We here recite the

nature of the homicides. Additional facts are discussed in the

segments of this opinion to which they have primary relevance.

THE TATE MURDERS: In August of 1969 Roman

Polanski and his wife, Sharon Tate Polanski, were tenants in residence

at 10050 Cielo Drive. During this time Mr. Polanski was out of the

country and Mrs. Polanski maintained the residence. Wojiciech

Frykowski and Abigail Folger lived with her. Mrs. Winifred Chapman was

the cook and housekeeper. Mrs. Chapman left the main residence between

4 and 4:30 p.m. on August 8, 1969. fn. 3

On the following day, August 9, Mrs. Chapman

returned to the Cielo Drive residence and discovered a ghastly scene.

The police were summoned and on investigation located five victims of

a brutal homicide. Just inside the entrance to the residence and near

the entry gate they located a Rambler automobile. Inside of the

vehicle they found the body of Steve Parent. The bodies of Frykowski

and Folger were on the front lawn. In the living room, connected by a

piece of rope, police located the bodies of Tate and Jay Sebring. A

towel was wrapped around Sebring's neck and covered his face.

Substantial amounts of blood and blood trails were

found about the property. The word "Pig" was written in blood on the

front door. fn. 4 [61 Cal. App. 3d 125] Examination of the bodies by

the coroner revealed that the victims suffered numerous injuries. Tate

suffered 16 stab wounds. Folger was found to have been stabbed 28

times. Sebring's body showed seven penetrating stab wounds and one

fatal gunshot wound. Frykowski's body exhibited 51 stab wounds and his

scalp had 13 lacerations apparently inflicted with a blunt instrument;

Frykowski's body had two gunshot wounds. Parent's body had five

gunshot wounds.

There was no apparent evidence of ransacking or

larceny. Jewelry and some money were found on the victims and on the

premises.

THE LA BIANCA MURDERS: On August 10, 1969,

Frank Struthers, the 16-year old son of Rosemary La Bianca, returned

from a vacation to his home at 3267 Waverly Drive. Expecting to find

his mother and stepfather, Leno La Bianca, Struthers instead

discovered the dead body of Leno La Bianca. Police were summoned to

the residence. Mr. La Bianca's body was in the living room, his face

covered with a blood-soaked pillow case. His hands were tied behind

his back with a leather thong. A carving fork was stuck in his

stomach, the two tines inserted down to the place where they divide.

On Mr. La Bianca's stomach was scratched the word "War." An electric

cord was knotted around his neck. The coroner's examination revealed

13 stab wounds, in addition to the scratches, and 14 puncture wounds

apparently made by the tines of the carving fork. A knife was found

protruding from his neck.

Mrs. La Bianca's body was found in a front bedroom.

Her hands were tied with an electric cord. A pillow case was over her

head and an electric cord was wound about her neck. Her body revealed

41 separate stab wounds.

There was no apparent evidence of ransacking.

Except for Rosemary La Bianca's wallet, no property appeared to be

missing from the victim's bodies or from their home. fn. 5

"Death to the Pigs" was written in blood on a wall

in the living room; over a door, "Rise"; and on a refrigerator door,

"Healter [sic] Skelter." [61 Cal. App. 3d 126]

The Conspiratorial Relationship fn. 6

At trial, respondent's evidence strongly supported

a theory that the homicides were the product of conspiratorial

relationships and activities. An enormous amount of evidence bearing

on the societal association between Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, Van

Houten and certain third persons was introduced. The scope of these

relationships in terms of time and intensity is germane. While it is

true that mere association with the perpetrator of a crime does not

prove criminal conspiracy, it is a starting place for examination.

(People v. Lewis (1963) 222 Cal. App. 2d 136, 144 [35 Cal.Rptr. 1].)

The very nature of this case and the theory of the

prosecution compel reference to circumstantial evidence of the conduct

and relationship of the parties. [1] People v. Kobey (1951) 105 Cal.

App. 2d 548 [234 P.2d 251] confirms that such reference is proper:

"Virtually the only method by which a conspiracy can be proved is by

circumstantial evidence -- the actions of the parties as they bear

upon the common design. It is not necessary to show directly that the

parties actually closeted themselves, attained the proverbial meeting

of the minds and agreed to undertake the unlawful acts. [Citation.] It

is a familiar principle of the law that in deriving whether an

agreement was unlawful the triers of the fact may consider the events

that occurred 'at or before' or 'subsequent' to the formation of the

agreement. From the proof of the occurrences beforehand and at the

time of the agreement linked with evidence of the overt acts a jury

may determine that a criminal conspiracy was formed. [Citations.] The

major portion of the evidence might consist of the conversations and

writings of the conspirators or it may consist of the overt acts done

pursuant to the conspiracy. Such acts may establish the purpose and

intent of the conspiracy and relate back to the agreement whose

purpose may be otherwise enshrouded in the hush-hush admonitions of

the conspirators. Whatever be the order of proof the jury has finally

to determine whether the alleged conspiracy has been established."

(People v. Kobey, supra, p. 562; see also, People v. Steccone (1950)

36 Cal. 2d 234, 237-238 [223 P.2d 17]; People v. Wheeler (1972) 23

Cal. App. 3d 290, 307 [100 Cal.Rptr. 198]; People v. Finch (1963) 213

Cal. App. 2d 752 [29 Cal.Rptr. 420].)

Sometime in 1967 Manson found his way to the

Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. While there he became

associated with young [61 Cal. App. 3d 127] girls and women who were

runaways, drop outs or otherwise disassociated with conventional

society. He obtained a Volkswagen bus, collected some of his female

companions, and began traveling about the country.

Ultimately, he established a commune of about 20

people at Chatsworth, California. Composed of Manson's companions from

Haight-Ashbury and others, the members were mostly young women, three

of whom had young children. The group became known as the "Family"

even though none were related by blood or marriage except for the

mothers and children. The Family, a community unto itself, rejected

conventional organizations and values of society. By August 1969 the

commune included Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie Van Houten,

and two other co-indictees -- Charles Tex Watson and Linda Kasabian.

At Chatsworth the Family occupied portions of an

established horse ranch owned and operated by George Spahn. Spahn

permitted the group to live there in exchange for the young women

doing certain domestic and secretarial work and the young men

maintaining the ranch trucks. The Family used certain bunkhouses, and

other buildings, fn. 7 and also maintained campsites, one of which was

located in Devils Canyon (the "Waterfall").

Without doubt, Manson was the leader of the Family.

The scope of his influence ranged from the most simple to the most

complex of matters. He decided where the Family would stay; where they

would sleep; what clothing they would have, and when they would wear

it; when they would take their evening meal; and when they would move.

Additionally, he concerned himself with the structure and composition

of the Family. Manson directed that the children not be cared for by

their natural mothers because he believed the children should be freed

of their mothers' "ego." He wanted the children kept out of sight

because he believed they were being watched by the Black Panthers.

Manson ordered one of the male members of the

Family, Paul Watkins, to get more females and bring them to him.

Instructing the female members of the Family to provide sexual favors

to members of the commune, and to do the same for outsiders for the

purpose of [61 Cal. App. 3d 128] recruiting new members, Manson also

directed them to deny their favors if enlistment seemed unlikely.

Manson established an elaborate system of security.

At his direction female members were ordered to stand guard. Members

were ordered to dye T-shirts black for use at night. Walkie talkies

were set up and used to connect the different campsites on the ranch.

Camouflage was used to cover some of the property. Clearly, Manson's

directions were designed to insulate the Family from the outside

world.

Manson's position of authority was firmly

acknowledged. It was understood that membership in the Family required

giving up everything to Manson and never disobeying him. His

followers, including the co-appellants, were compliant. They regarded

him as infallible and believed that he was a "God man" or Christ.

Family member Danny DeCarlo testified that each co-appellant said that

"Charlie sees all and knows all." Kasabian was told by the others "We

never question Charlie. We know that what he is doing is right."

The Family's willingness to follow Manson's

directions is salient to the People's theory of the case. The

establishment and retention of his position as the unquestioned leader

was one of design. A fundamental method used by him to inculcate the

Family with his views of life, values, and philosophy was to address

them after evening meals. On these occasions Manson would do most of

the talking or play his guitar and sing songs, many of which purported

to carry profound messages. Manson firmly believed these gatherings

were necessary. fn. 8 [61 Cal. App. 3d 129]

He frequently repeated to members of the Family

(including the co-appellants, collectively or individually)

exhortations on the relationship between love and death. Manson's

preoccupation with the subject is vividly revealed in a statement by

Manson to Paul Watkins: "In order to love someone you must be willing

to die for them and must be willing to kill them, too. You must be

willing to have them kill you. You must be willing to experience

anything for them."

Manson had a fascination with the Beatles fn. 9 and

with one of their songs, "Helter Skelter" in particular. Telling the

Family and others that the Beatles were speaking to him and warning of

imminent conflict between the blacks and the whites, Manson gave the

name Helter Skelter to a chimerical vision of a race war. To the

Family, Helter Skelter meant the occurrence of a revolution started by

blacks to gain control of the world to subdue the conventional

establishment of the college educated, wealthy white community and

power structure. These whites were referred to by Manson and his

followers as "Pigs."

Manson frequently discussed this revolution with

members of the commune, describing in detail how whites would be

atrociously murdered by blacks. The killings would be marked by the

symbolic ritual of writing with the blood of the victims. A major

theme of Helter Skelter was that Manson would lead his followers to

safety during the apocalyptic event and, at its conclusion, he and the

Family would emerge from this place of safety -- a bottomless pit

located in Death Valley -- and take control of the world and restore

order. Connected to the aberration of Helter Skelter was Manson's

equation of himself to Jesus Christ, his followers as the true

Christians and members of conventional white society as the Romans --

otherwise designated "Pigs."

A further facet of this fantasy included Manson's

pronounced interest in death. One witness aptly testified, "Death is

Charlie's trip. It really is." Manson spoke of Helter Skelter

constantly. With the passage of time, his concern became intense. He

finally proclaimed he would have to cause the revolution. There is

specific evidence that Manson declared the belief that he would have

to show the "nigger" how to do it. Family member Dianne Lake testified

that in the summer of 1969 Manson told her "... we had to be willing

to kill pigs to help the black people start revolution Helter

Skelter." In the presence of Lake and of the co-appellants Manson

said, "I am going to have to start the revolution." By the [61 Cal.

App. 3d 130] summer of 1969, the time he predicted Helter Skelter

would begin, he talked about it more and more. Quite obviously, a

fundamental part of life in the commune entailed exposure to Manson's

obsession with Helter Skelter.

Evidence of Other Crimes

To amplify the extent of Manson's influence on the

Family, testimony of certain sexual activities was presented.

Kasabian testified that on one occasion an

unidentified 16-year old girl, clad only in bikini panties, was placed

in the center of a room. Many of the Family members were present,

including appellants. Manson made advances to this girl. She bit him.

He struck her in the face, knocking her to the ground, and committed

an act of sexual intercourse with her. He then bid the other male and

female members to engage in sexual acts with the girl. Manson then

directed all the members of the Family to take off their clothing and

to "make love" together. They followed his directions.

Barbara Hoyt, a witness for respondent, was a

member of the Family. She described an incident where she was ordered

by Manson to orally copulate Juan Flynn, a frequent associate of the

Family. Hoyt testified that she did not want to perform the act, but

did so because she was afraid of Manson.

[2a] Relying on Evidence Code section 1101, Manson

contends the above matters were highly prejudicial and erroneously

admitted. We find no error. [3] "[E]vidence of other crimes is

inadmissible as regards guilt when it is offered solely to prove

criminal disposition because the probative value of such evidence as

to the crime charged is outweighed by its prejudicial effect. However,

such evidence may be properly admissible if it is offered to prove a

fact material to the charged crime and meets the general tests of

relevancy as to such fact. [4] '[T]he general test of admissibility of

evidence in a criminal case is whether it tends logically, naturally,

and by reasonable inference, to establish any fact material for the

People or to overcome any material matter sought to be proved by the

defense.' [Citations.]" (People v. Durham (1969) 70 Cal. 2d 171, 186

[74 Cal.Rptr. 262, 449 P.2d 198], cert. den., 395 U.S. 968 [23 L.Ed.2d

755, 89 S.Ct. 2116].) [61 Cal. App. 3d 131]

[2b] Although the evidence concerning these events

was indeed dramatic, it nevertheless reasonably tended to show

Manson's leadership of the Family, fn. 10 the inference being that if

Manson could induce bizarre sexual activities, he could induce

homicidal conduct. While the evidence is less than flattering, its

prejudicial character is outweighed by its evidentiary value showing

Manson's involvement in the murders. (People v. Randolph (1970) 4 Cal.

App. 3d 655, 661 [84 Cal.Rptr. 559].)

Kasabian's Testimony

The only direct evidence tying appellants to the

commission of the Tate-La Bianca murders was the testimony of Family

member Linda Kasabian. She testified that on the evening of August 8,

1969, at the Spahn ranch, Manson told her, "Now is the time for Helter

Skelter." He ordered her to get a change of clothing, a knife and her

driver's license. Kasabian complied and when she returned with those

articles Manson told her "... to go with Tex and to do what Tex told

[her] to do." fn. 11 She then proceeded to an automobile. Watson was

standing next to the driver's side talking with Manson. Atkins and

Krenwinkel were in the back seat. Kasabian and Watson then got in the

car and began to leave. At that moment Manson called for them to stop

and they did. Manson went up to the car, put his head in and said,

"You girls know what I mean, something witchy." fn. 12 Watson then

drove directly to 10050 Cielo Drive, where he stopped the car, got out

and appeared to cut some overhead wires. He then turned the vehicle

around and parked it. Kasabian held three knives and one gun which

Watson had asked her to discard if they were stopped en route.

The car was parked and all four got out. With

Watson carrying some rope, they proceeded up a hill, over an

embankment or fence and into the outer premises of a private

residence. A car approached towards a gate opening onto the street. As

it stopped, Watson leaped forward with gun in hand. The driver said,

"Please don't hurt me I won't say anything." Watson shot him. fn. 13

Kasabian saw the driver slump over. Tex turned off the ignition. [61

Cal. App. 3d 132]

They proceeded to the house. Watson ordered

Kasabian to go to the back to look for open doors or windows. She did

as directed, found none, and returned to the front of the house.

Kasabian saw Watson cut a window screen. She did not, however, see

anyone enter the house as Watson then told her to return to the "car"

to stand lookout. fn. 14 She did as directed.

Within a few minutes Kasabian heard screams and the

words "No, please, no" coming from the house. She ran to the house.

She saw a man exiting with blood on his face. The man fell to the

ground. Atkins came out and Kasabian said "Sadie, please make it

stop." fn. 15 Atkins replied, "It is too late." While these remarks

were being exchanged the man who had fallen got up. He was attacked by

Watson who stabbed and clubbed him. Kasabian observed Krenwinkel with

a knife in her hand chasing a woman. Kasabian ran back to the car

Watson had parked.

Eventually Krenwinkel, Atkins and Watson returned

to that car. They had blood on their clothes. Watson got behind the

wheel, the others got in, and they all left. Kasabian discovered they

no longer had her knife with them and that a portion of the grip of

the gun was broken. fn. 16 It had been intact when she saw it earlier

that night. In the course of traveling away from the residence Watson,

Atkins and Krenwinkel changed clothes. At Watson's direction Kasabian

threw the removed clothing out of the car and later did the same with

the remaining knives. The group returned to the Spahn ranch to find

Manson outside waiting for them. He asked if they felt any remorse and

they said no. He directed them not to talk about the event with anyone

at the ranch and to get some sleep. They then retired.

After dinner on the following day, Kasabian was

with appellants Krenwiel and Van Houten at the Spahn ranch. Manson

told the three women to get a change of clothes and to meet him at the

bunkhouse. When they arrived there Manson, Atkins, Watson, Krenwinkel

and Steven Dennis Grogan, another Family member, were present. Manson

told them they were going out again that night. He said the killings

of the preceding night were too messy and he was going to show them

how to [61 Cal. App. 3d 133] do it. As they all entered the car Manson

gave Kasabian a leather thong. With Kasabian driving and Manson giving

directions, they drove about in a random fashion, making some stops to

permit Manson to check out locations for the ostensible purpose of

locating victims to murder.

After driving about through a maze of roads, Manson

ordered Kasabian to stop the car in front of a residence on Waverly

Drive. Kasabian recognized the home as belonging to Harold True, a man

known to some of the Family. She told Manson he could not go there.

Manson stated he was going next door (the La Bianca residence). Manson

got out and left the others. Several minutes later he returned. He

said that he had tied up a man and a woman. Manson then spoke directly

to Van Houten, Krenwinkel and Watson, advising, "Don't let them know

you are going to kill them."

After the others exited, Manson got back in the car

with Kasabian, Atkins and Grogan. Manson handed Kasabian a wallet,

telling her he wanted to dispose of it so that it would be found by a

black person who would use the credit cards. His expressed hope was

that the blacks would be blamed for the crime. Leaving Van Houten,

Krenwinkel and Watson at the La Bianca residence, Kasabian, Atkins,

Grogan and Manson departed. They stopped at a gas station where

Kasabian hid the wallet in a restroom. Manson then drove to the beach

where he spoke to Kasabian about an actor she had met. Manson gave

Kasabian a small pocket knife and instructed her to kill the actor.

She showed Manson the apartment house where the actor lived. fn. 17

Manson then gave Grogan a gun and told Grogan and Atkins to go with

Kasabian into the actor's apartment. After telling all three to

hitchhike back, Manson told Atkins to go to the Waterfall when she

returned. Manson then left.

Kasabian claimed she wanted to abort the suggested

killing and succeeded in doing so. She testified that she purposely

led the other two to the wrong apartment. Kasabian, Grogan and Atkins

then started their return and arrived back at the ranch mid-morning of

the next day to find Manson asleep in the parachute room.

Kasabian Immunity

From the outset of her testimony -- July 27, 1970

-- Kasabian made it clear that she had been tendered a grant of

immunity (Pen. Code, [61 Cal. App. 3d 134] § 1324). However, no

written request for her immunity was filed with the court until August

10, 1970, after the completion of direct examination. On that date the

trial judge signed the order requiring her to answer questions. fn. 18

[5] Manson, complaining that the failure to rule on

Kasabian's immunity status prior to the completion of her direct

testimony constituted reversible error, relies on the following

declaration in People v. Walther (1938) 27 Cal. App. 2d 583, 590-591

[81 P.2d 452]: "We may assume that the district attorney has a right

to arbitrarily select one of two coconspirators to whom he may tender

immunity from prosecution in reward for his state's evidence against

his colleague, but such evidence is open to suspicion lest the

temptation thus to escape a threatened penalty of law may result in

unreliable testimony. Under such circumstances the evidence of a

coconspirator should be examined with great care. When a codefendant

who is a coconspirator has been offered immunity from prosecution in

reward for his testimony, the cause should be promptly dismissed

against him. Otherwise, the maintenance of the action against him

throughout the trial may serve to intimidate the witness and furnish

an inducement for him to color his testimony."

We do not interpret Walther as standing for an

inflexible rule of law. Walther instructs that pending charges should

be promptly dismissed. We therefore hold that the admissibility of

testimony of a witness who has been offered immunity must turn on the

facts of each case. In contrast to the Walther court, the Supreme

Court confronted a similar situation with a different result in People

v. Lyons (1958) 50 Cal. 2d 245 [324 P.2d 556]. In Lyons, the defendant

complained that his accomplices had been induced to testify

untruthfully against him. Prior to testifying the accomplices had

entered a plea of guilty to certain charges. The court had postponed

the sentencing of the accomplices until they had testified against the

defendant. The prosecution conceded that the accomplices had been

induced to testify by promises of reduced sentences.

We are of the opinion that no meaningful

distinction exists between testimony obtained as the result of a grant

of immunity and testimony obtained as the result of a plea bargain.

Both "furnish the defendant [61 Cal. App. 3d 135] with a powerful

weapon for attacking the credibility of the inherently suspect

witnesses. ..." (People v. Lyons (1958) 50 Cal. 2d 245, 265 [324 P.2d

556].) Neither is necessarily unfair as a matter of law.

It is naive to suggest that an offer of immunity is

not enticing to a witness who would otherwise be exposed to serious

criminal charges. It is equally naive to suggest that the immunity

should be given entirely, completely and finally without first

obtaining the testimony that invited the grant of immunity in the

first place. A fundamental purpose of Penal Code section 1324 is to

make possible the prosecution of criminal conspiracies. (People v.

Pineda (1973) 30 Cal. App. 3d 860, 866-868 [106 Cal.Rptr. 743].)

Authority cited in support of appellants'

contention is not applicable. The evidence does not show that Kasabian

was offered immunity on the condition that her testimony produce a

conviction (see People v. Green (1951) 102 Cal. App. 2d 831, 834-835

[228 P.2d 867]) nor does it show that the trial judge or anyone else

gave Kasabian reason to believe that her testimony must conform to

certain statements that she made to any law enforcement officers. (See

Rex v. Robinson (1921) 30 B.C. 369 [70 D.L.R. 755]; People v. Medina

(1974) 41 Cal. App. 3d 438, 452-455 [116 Cal.Rptr. 133].) There is

absolutely no evidence that the offer of immunity to Kasabian was

conditioned on anything other than her testifying fully and fairly

about her knowledge of the Tate-La Bianca murders. Her testimony was

properly admitted.

Collaterally, Manson points out that prior to

calling Kasabian as a witness, she was interviewed by the prosecution.

From that he invites the conclusion that her testimony is nothing more

than a script written by respondent. The fact of her interview is

hardly startling. Common sense generally compels lawyers to interview

witnesses prior to calling them. Pragmatic lawyers do not call

witnesses unless they expect favorable testimony. Manson was not deed

a fair trial by reason of the interview.

Competency of Kasabian

[6] Prior to Kasabian's testimony Manson moved to

have her examined by a court-appointed psychiatrist to determine her

competency. fn. 19 [61 Cal. App. 3d 136] The motion was supported by

declarations fn. 20 asserting that Kasabian had used LSD in

substantial amounts and over a period of several years. The

declaration of A. R. Tweed, M.D., was also attached. Doctor Tweed

identifies himself as a psychiatrist; his declaration renders the

opinion that habitual long term use of LSD can affect an individual's

ability to perceive and otherwise adversely affect mental orientation

and declares that a psychiatric examination of Kasabian "would be an

important tool to evaluate" her mental status and ability "to give a

picture as undistorted as possible." The court denied Manson's

application to have Kasabian examined and permitted the witness to

testify. By her own admission Kasabian had used LSD approximately 50

times since 1965. She used other hallucinogenics as well. However, she

testified that, with one possible exception, she did not use any LSD

or other hallucinogenic between May and August, 1969. She admitted to

the use of marijuana during this period.

Relying on Ballard v. Superior Court (1966) 64 Cal.

2d 159 [49 Cal.Rptr. 302, 410 P.2d 838, 18 A.L.R.3d 1416], Manson and

his co-defendants reasserted their demand that Kasabian be examined by

a court-appointed psychiatrist. Each time the motion was made it was

denied.

To clarify the issue we note that appellants'

contention has two parts: (1) that Kasabian was incompetent because

she was so disabled by the use of LSD that she could not perceive that

about which she purported to testify; and (2) that the use of LSD had

so disabled Kasabian's mind that her testimony was not credible.

The trial court is vested with the responsibility

to determine competence (People v. Blagg (1970) 10 Cal. App. 3d 1035,

1039 [89 Cal.Rptr. 446]) by the standard found in Evidence Code

sections 700-702. Here our main concern is with Evidence Code section

702 that "the testimony of a witness concerning a particular matter is

inadmissible unless he has personal knowledge of the matter. Against

the objection of a party, such personal knowledge must be shown before

the witness may testify concerning the matter. [¶] A witness' personal

knowledge of a matter [61 Cal. App. 3d 137] may be shown by any

otherwise admissible evidence, including his own testimony."

The code requirement of "personal knowledge"

includes the capacity to perceive accurately and the capacity to

recollect what has been perceived. (Jefferson, Cal. Evidence Benchbook

(1972) § 26.2, p. 351.) This standard points to two time frames: (1)

the time of perception; (2) the time of recollection. In the instant

case there was no evidence that Kasabian was under the influence of

any hallucinogenic at the time of the critical events about which she

testified or at the times she testified. Notwithstanding Dr. Tweed's

declaration concerning the possible affects and delayed reactions --

flashbacks -- that attend the use of LSD, the record does not support

a disqualification of the witness under the Evidence Code as a matter

of law. While the impeaching effect of her use of hallucinogenics was

properly placed before the jury, her competence to be a witness was a

question properly resolved by the court. (United States v. Barnard

(9th Cir. 1973) 490 F.2d 907, 912, cert. den., 416 U.S. 959 [40

L.Ed.2d 310, 94 S.Ct. 1976]; People v. McCaughan (1957) 49 Cal. 2d

409, 420 [317 P.2d 974].)

Appellants reliance onBallard v. Superior Court,

supra, is misplaced. Ballard and its progeny provide for appointment

of a psychiatrist to examine a prosecuting witness in a sex offense

case to ascertain credibility. The procedure, which may result in the

psychiatrist testifying to give his opinion concerning the veracity of

the witness, is applicable to the subject of impeachment and not to

competency. Whether or not a psychiatrist is appointed is a matter

within the sound discretion of the trial court. (People v. Russel

(1968) 69 Cal. 2d 187, 195 [70 Cal.Rptr. 210, 443 P.2d 794].)

The nature of the charges in this case is such that

psychiatric testimony for purposes of impeachment would be

extraordinary. "In cases not involving sex offenses California courts

usually reject attempts to impeach a witness by means of psychiatric

testimony." (People v. Johnson (1974) 38 Cal. App. 3d 1, 6-7 [112

Cal.Rptr. 834].) While we do not suggest that Ballard is necessarily

limited to cases involving sex offenses, we here accept the admonition

"[that a] psychiatrist's testimony on the credibility of a witness may

involve many dangers: the psychiatrist's testimony may not be

relevant; the techniques used and theories advanced may not be

generally accepted; the psychiatrist may not be in any better position

to evaluate credibility than the juror; difficulties may arise in

communication between the psychiatrist and the jury; too much reliance

may be [61 Cal. App. 3d 138] placed upon the testimony of the

psychiatrist; partisan psychiatrists may cloud rather than clarify

issues; the testimony may be distracting, time-consuming and costly."

(People v. Russel, supra, 69 Cal. 2d at p. 195, fn. 8.)

The trial court's denial of the motion for

psychiatric examination was proper. In 18 days of examination Kasabian

testified clearly and comprehensibly. Her descriptions were not

unclear and her demeanor was candid. Her testimony in its entirety

demonstrates her competency. fn. 21 (People v. Pike (1960) 183 Cal.

App. 2d 729, 732 [7 Cal.Rptr. 188].) We find no error. fn. 22

Corroboration

Kasabian's description of her involvement in the

Tate-La Bianca murders would have justified her prosecution for those

offenses. Accordingly, the trial court properly characterized her as

an accomplice as a matter of law. Consequently, Kasabian's testimony

must be corroborated with respect to each appellant. (Pen. Code, §

1111.) fn. 23

[7] The character and nature of corroborative

evidence may be very general and may vary according to the

circumstances of each case. (People v. Luker (1965) 63 Cal. 2d 464,

469 [47 Cal.Rptr. 209, 407 P.2d 9].) On the other hand, the standard

by which the sufficiency of such evidence is determined has been

repeatedly articulated. [8] In People v. Hathcock (1973) 8 Cal. 3d

599, 617 [105 Cal.Rptr. 540, 504 P.2d 476], the Supreme Court

succinctly stated that standard as follows: "'The evidence required

for corroboration of an accomplice "need not corroborate the

accomplice as to every fact to which he testifies but is [61 Cal. App.

3d 139] sufficient if it does not require interpretation and direction

from the testimony of the accomplice yet tends to connect the

defendant with the commission of the offense in such a way as

reasonably may satisfy a jury that the accomplice is telling the

truth; it must tend to implicate the defendant and therefore must

relate to some act or fact which is an element of the crime but it is

not necessary that the corroborative evidence be sufficient in itself

to establish every element of the offense charged." [Citations.]

Moreover, evidence of corroboration is sufficient if it connects

defendant with the crime, although such evidence "is slight and

entitled, when standing by itself, to but little consideration."

[Citations.]'"

Commonly a defendant's own statements and

admissions are found to be sufficient corroboration to support the

testimony of an accomplice. (People v. Negra (1929) 208 Cal. 64, 69

[280 P. 354].) This case is no exception. Although appellants'

admissions and declarations are not the exclusive corroborative

evidence, they are the most substantial. Appellants have asserted

various grounds of reversible error with respect to some of this

corroborative evidence. These evidentiary objections are here

considered in their substantive context with respect to each

appellant.

MANSON CORROBORATION -- ITEM 1: Among the

circumstances implicating Manson in the Tate-La Bianca murders are his

frequently proclaimed prophesies of Helter Skelter. Predicting a war

started by blacks "ripping off" white families in their homes, Manson

stated that "Blackie" (the blacks) would revolt against and kill the

"Pigs" (the white establishment). From 1968 through the summer of 1969

Manson told various people about Helter Skelter and what it entailed.

Family member Barbara Hoyt testified that between

April and September 1969 Manson spoke of Helter Skelter frequently. He

said Helter Skelter "... was coming down fast" and that he "would like

to show the Blacks how to do it."

Dianne Lake testified that in June, July and August

of 1969 Manson stated to various members of the commune, including

coappellants, that they "had to be willing to kill pigs to help the

black people start the revolution 'Helter Skelter'." During the summer

of 1969, Manson repeatedly stated that he would have to start the

revolution. [61 Cal. App. 3d 140]

Another witness testified that in July 1969 Manson

told him: "'Well, I have come down to it, and the only way to get

going is to show the black man and the pigs is to go down there and

kill a whole bunch of these fuckin' pigs.'"

Paul Watkins, testifying that Manson told him

Helter Skelter would start in the summer of 1969, described Manson's

plan: "[T]here would be some atrocious murders; ... some of the Spades

from Watts would come up into the Bel-Air and Beverly Hills District

and just really wipe some people out, just cut bodies up and smear

blood and write things on the wall in blood, and cut little boys up

and make the parents watch. All kinds of just super-atrocious crimes

that really would make the white man mad." Manson told Watkins the

deeds would precipitate a retaliation by whites who would shoot "black

people like crazy;" ultimately Muslims would appear and shame the

white people for their reaction. The blacks would murder the whites by

"sneaking around and slitting their throats." According to Watkins,

Manson declared that "He had to bring [Helter Skelter] down."

Significantly, Manson's description of the killings to occur during

Helter Skelter included the writing of the word "Pig" on walls or

otherwise smearing walls with the blood of the victims.

[9] Where the identity of the accused is in issue,

his prior conduct may, under proper circumstances, be admitted to

prove intent, motive or knowledge of a particular plan and scheme that

reasonably tends to connect him to the crime in question. (Evid. Code,

§ 1101, subd. (b).) The testimony of these several witnesses tends to

confirm that Manson was the originator and purveyor of a warped

fantasy. The consistency of the statements reveals an intense

obsession on Manson's part to see the fulfillment of his prediction.

The similarity between the Helter Skelter prophesy and the manner in

which the Tate-La Bianca murders occurred is sufficiently great to be

characterized as strong circumstantial evidence to corroborate the

testimony of Kasabian. (People v. Alcalde (1944) 24 Cal. 2d 177 [148

P.2d 627]; People v. Wilt (1916) 173 Cal. 477 [160 P. 561].)

Manson argues that the statements of intent to do a

future act were not directed against the victims of the crimes with

which he was charged and that it was therefore error to admit them. A

similar contention has been rejected by our Supreme Court. It is only

necessary that the threats show "some connection with the injury

inflicted on the deceased." (People v. Wilt, supra, 173 Cal. at p.

482.) [61 Cal. App. 3d 141]

The declarations of intent attributed to Manson are

admittedly general. However, his declarations to foment bloodshed,

even without specific reference to a particular victim, are relevant

because the actual method and manner of the killings substantially

conformed to Manson's predictions. The indefiniteness of a threat is

not necessarily an obstacle to its admission if there is sufficient

collateral evidence to bring the ultimate victims within the generic

class of the subject of the threat. (People v. Craig (1896) 111 Cal.

460, 466 [44 P. 186]; State v. Presley (1973) 110 Ariz. 46 [514 P.2d

1234, 1235]; 1 Wigmore on Evidence, § 106; 40 C.J.S., Homicide, §

206(c), pp. 1110-1111.) Here, even though Manson's declarations never

included a specific threat against the victims of the Tate-La Bianca

murders, they, in fact, came within his generic threats and were

properly admitted.

Moreover, the declarations were properly admitted

as evidence of the particular method and mode by which a crime was to

be committed in the future. They were relevant to the issue of motive

and knowledge which in turn tends to prove identity. (See People v.

Neal (1950) 97 Cal. App. 2d 668, 673 [218 P.2d 556].)

Manson's pronouncements pertaining to Helter

Skelter are proper corroboration of Kasabian's testimony. Even slight

and circumstantial evidence which, standing alone, would be

insufficient for conviction and entitled to little consideration, will

serve to corroborate an accomplice. (People v. Simpson (1954) 43 Cal.

2d 553, 563 [275 P.2d 31]; People v. Wayne (1953) 41 Cal. 2d 814, 822

[264 P.2d 547]; People v. Claasen (1957) 152 Cal. App. 2d 660, 664

[313 P.2d 579].) The probative value of this evidence to corroborate

Manson's participation in the murders outweighed any undue prejudice;

it was properly admitted in accordance with Evidence Code section

1101, subdivision (b). (People v. Beamon (1973) 8 Cal. 3d 625, 632-633

[105 Cal.Rptr. 681, 504 P.2d 905].)

MANSON CORROBORATION -- ITEM 2: Juan Flynn was a

witness for the prosecution. He testified that he lived at Spahn

ranch, earning his room and board as a laborer. While there he met

Manson and the other members of the commune. Flynn did not become a

member of the Family but did frequently associate with its members on

an intimate basis. Flynn testified that Manson admitted to him that he

was "doing all [the] killings." fn. 24 This testimony was limited to

Manson only. [61 Cal. App. 3d 142]

On August 18, 1970, prior to testifying at this

trial, Flynn had given a statement to the Los Angeles Police

Department. Appellants were provided with a 16-page report of that

interview. The report did not refer to the foregoing incident and

admission. fn. 25 Sometime before Flynn's testimony, appellants were,

however, provided with a later written communication revealing

Manson's admission as quoted above. fn. 26 Flynn's prior inconsistent

statement omitting reference to Manson's admission was used to impeach

Flynn's subsequent testimony including the admission.

In an attempt to rehabilitate Flynn, respondent

called David Steuber, a California highway patrolman. Steuber

testified that he interviewed Flynn on December 19, 1969, at Shoshone,

California, and that he recorded the interview. The recording,

produced in court, includes a statement by Flynn substantially similar

to his in-court testimony concerning Manson's admission. Ultimately,

the critical portion of the Steuber tape was played for the jury. [61

Cal. App. 3d 143]

Before the jury heard the tape appellants made

strenuous objections on several grounds, all of which were overruled.

[10a] Manson now assigns as reversible error the admission of the

Steuber tape.

There is no disagreement that Flynn's failure to

reveal this critical admission when interviewed by the Los Angeles

Police Department raised the specter of recent fabrication. [11] It is

elementary that recent fabrication may be inferred when it is shown

that a witness did not speak about an important matter at a time when

it would have been natural for him to do so. When that inference does

arise, it is generally proper to permit rehabilitation by a prior

consistent statement. "Different considerations come into play when a

charge of recent fabrication is made by negative evidence that the

witness did not speak of the matter before when it would have been

natural to speak. His silence then is urged as inconsistent with his

utterances at the trial. The evidence of consistent statements at that

point becomes proper because 'the supposed fact of not speaking

formerly, from which we are to infer a recent contrivance of the

story, is disposed of by denying it to be a fact, inasmuch as the

witness did speak and tell the same story.'" (People v. Gentry (1969)

270 Cal. App. 2d 462, 473 [76 Cal.Rptr. 336].)

[10b] Respondent asserts that the Steuber tape was

admissible pursuant to Evidence Code section 1236. fn. 27 Manson

argues that section 1236 is inapplicable because the witness was shown

to have a bias or motive for fabrication before the time of the prior

consistent statement. (Evid. Code, § 791, subd. (b).) fn. 28

The predicate for Manson's assertion turns on

collateral facts. On August 16, 1969, Spahn ranch was raided by the

Los Angeles County Sheriff's office in connection with suspected

criminal activity involving [61 Cal. App. 3d 144] the theft of dune

buggies. The raid resulted in a number of people, including Flynn,

being arrested. On cross-examination Flynn was asked whether or not he

was mad at Manson because of this incident. Flynn answered that he

believed Manson and the Family were responsible for the raid but that

he did not blame Manson. Additionally, Flynn testified that he worked

off and on as an actor. On cross-examination Flynn was asked if he was

testifying in order to obtain fame, the clear insinuation being that

Flynn was cooperating as a prosecution witness in order to advance his

own theatrical ambitions. Flynn denied that suggestion. Manson's

argument turns more on the insinuation of the questions than on any of

Flynn's testimony. The questions, and not Flynn's answers, suggest

that Flynn developed a bias as a result of his being arrested on

August 16, 1969.

Appellant's argument fails because it ignores the

fact that Evidence Code section 791 has two parts. Subdivision (a)

permits evidence of a prior consistent statement to rehabilitate a

witness impeached by a statement contrary to his trial testimony while

subdivision (b) allows the prior consistent statement to rehabilitate

after an express charge or implication of recent fabrication or of

bias. Whether or not subdivision (b) of Evidence Code section 791 is

applicable is of no consequence to the application of subdivision (a)

of that section. Even if it is assumed the Steuber tape postdated the

inception of any bias or motive to fabricate on the part of Flynn,

that fact would only bear on its introduction within the circumstances

described in subdivision (b) of section 791. It certainly would not

preclude application of subdivision (a) of section 791 and the

introduction of the Steuber tape predating the August 16, 1970,

interview. The statement was properly admitted. (Cf. People v. Duvall

(1968) 262 Cal. App. 2d 417, 420-421 [68 Cal.Rptr. 708]; People v.

Walsh (1956) 47 Cal. 2d 36, 41-43 [301 P.2d 247].)

An additional complaint about the Steuber tapes is

based on Manson's assertion that the prosecution failed to comply with

a discovery order. The contention lacks merit. The prosecution,

claiming it first learned of the Steuber interview during the course

of Flynn's cross-examination, represented that it had no contact with

Steuber or the District Attorney of Inyo County for whom Steuber was

acting until after Flynn was under cross-examination. The deputy

district attorney offered to be sworn and to testify to that fact.

Furthermore, appellant had the opportunity to

cross-examine both Steuber and the District Attorney of Inyo County

and thus to discover [61 Cal. App. 3d 145] the circumstances by which

the representatives of Los Angeles County came into possession of the

Steuber tapes. Having foregone the opportunity to ascertain whether or

not the "Steuber tape" was known to the prosecution in advance of

trial, Manson cannot now successfully claim a violation of the

discovery order. There is simply a void in the evidence that appellant

did nothing to fill even with the opportunity to do so.

Another contention made by Manson with respect to

the introduction of the Steuber tape is that the tape was

"suppressed." [12] Suppressed evidence is that evidence favorable to

the defendant which the prosecution fails to disclose prior to or

during trial. (People v. Ruthford (1975) 14 Cal. 3d 399, 406 [121

Cal.Rptr. 261, 534 P.2d 1341].) [10c] In this case, Flynn's testimony

concerning Manson's admission was made known to appellant before

trial. Delay in producing the tape itself until after trial commenced

does not transform Flynn's testimony into "suppressed" evidence. fn.

29

Three other evidentiary complaints that Manson

asserts concerning Flynn's testimony must be discounted.

[13] Flynn's testimony concerning threats on his

life, relevant to his state of mind and credibility, was properly

admitted despite Manson's assertion to the contrary. The threats tend

to explain Flynn's delay in relating some of his trial testimony.

While it is generally true that a defendant cannot be held accountable

for threats made against witnesses without his consent or authority

(People v. Terry (1962) 57 Cal. 2d 538, 565-566 [21 Cal.Rptr. 185, 370

P.2d 985]), here the court admonished the jury to consider Flynn's

testimony "... solely as to what this witness' [61 Cal. App. 3d 146]

state of mind may have been with respect to relating to law

enforcement persons the substance of the matters covered by his

testimony in this trial. This testimony is not to be considered for

any purpose with regard to Mr. Manson, that is, his testimony on these

conversations." The admonition removed the impediment to such

testimony since Manson was not held accountable for it.

Another aspect of Flynn's testimony drawing charges

of error was his statement that on one occasion Manson said, "Well,

why don't we go in there and tie them up and cut them to pieces."

Referring to occupants of a house with whom Flynn was acquainted,

Flynn's testimony was in response to a question concerning a

conversation Flynn had with Manson about the epithet "pig." The

question was asked on cross-examination after the subject was raised

on direct. Consequently, inquiry and response were proper. (Evid.

Code, § 356; Long v. Cal. Western States Life Ins. Co. (1955) 43 Cal.

2d 871, 881 [279 P.2d 43].) Even so, at the insistence of appellants'

counsel, the court admonished the jury to disregard the declaration

attributed to Manson. No prejudice resulted.

[14] Flynn testified that on one occasion he saw

Manson fire a handgun, and he identified an exhibit otherwise

identified as one of the murder weapons as being that gun. Flynn's

testimony indicated that Manson fired the gun at or in the direction

of Flynn and a third person. Manson cites the receipt of this

testimony as prejudicial error. We disagree. Manson's use of the

handgun is circumstantially relevant. It tends to connect him to one

of the instruments of the Tate murder. The court admonished the jury

to disregard Flynn's testimony insofar as it pertained to Manson's

target. That admonition was sufficient and there was no error.

MANSON CORROBORATION -- ITEM 3: The handgun

introduced in evidence as People's Exhibit 40 was a weapon to which

Manson had access. Consistent with Kasabian's testimony concerning the

use of a gun by Watson to strike Frykowski on the head, pieces of a

righthand pistol grip were found at the Tate residence. These pieces

fit People's Exhibit 40. fn. 30 While there is no contention that

Manson was at the Tate residence, evidence that a weapon used by him

was a weapon used in the Tate murders has some probative value in

demonstrating a relationship between him and the event. (People v.

Buono (1961) 191 Cal. App. 2d 203, [61 Cal. App. 3d 147] 220 [12

Cal.Rptr. 604]; People v. Channell (1951) 107 Cal. App. 2d 192, 197

[236 P.2d 654].)

MANSON CORROBORATION -- ITEM 4: It is

uncontradicted that prior to August 1969, Manson was acquainted with

the Cielo Drive residence and with the home of Harold True adjoining

the La Biancas' home on Waverly Drive. Even though no homicide

occurred in True's residence, the circumstance that Manson was

familiar with both general locations is susceptible to an

interpretation exceeding mere coincidence. [15] "The state of mind of

a person is a fact to be proved like any other fact when it is

relevant to an issue in the case; and when knowledge of a fact has

important bearing upon the issues, evidence is admissible which

relates to the question of the existence or nonexistence of such

knowledge, [citations]." (Larson v. Solbakken (1963) 221 Cal. App. 2d

410, 418 [34 Cal.Rptr. 450].)

MANSON CORROBORATION -- ITEM 5: The fact that Leno

La Bianca's hands were tied with leather thongs is circumstantially

probative. Several witnesses testified that Manson frequently wore

such thongs around his neck and in November of 1969 leather thongs

were recovered from Manson's clothing.

[16a] AGGREGATE OF MANSON CORROBORATION: In the

aggregate, the evidence is more than sufficient. [17] "Although the

corroboration must connect the defendant with the commission of the

offense, it 'may be slight and entitled to little consideration when

standing alone.' [Citation.] The requisite corroboration may be

provided by circumstantial evidence." (People v. Valerio (1970) 13

Cal. App. 3d 912, 923 [92 Cal.Rptr. 82].)

[16b] In addition to Manson's admissions, his

relation to the Buntline revolver (Exh. 40), his familiarity with the

locations of the crimes, and his habit of having on his person the

same kind of material used to bind one of the victims are, in the

aggregate, circumstantial evidence corroborating the testimony of

Kasabian. (People v. Henderson (1949) 34 Cal. 2d 340 [209 P.2d 785].)

[18a] CORROBORATION -- ATKINS, KRENWINKEL, VAN

HOUTEN: An important part of the evidence produced to corroborate

accomplice testimony against Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten

consisted of their independent admissions and declarations. These are

summarized as follows: [61 Cal. App. 3d 148]

(1) Atkins -- After her arrest and while

incarcerated at Sybil Brand Institute awaiting trial, Atkins confided

in two other inmates concerning her participation in the Tate murder.

These inmates, Virginia Graham Castro and Roni Howard, informed the

law enforcement agencies of the admissions. Another inmate, Roseanne

Walker, testified that she and Atkins listened to a broadcast

concerning the Tate and La Bianca murders. Atkins commented on the

broadcast, "That ain't the way it went down." In addition to the

statements made to fellow inmates, Atkins wrote several letters

inculpating herself in the Tate-La Bianca murders. Of these, three

were marked and admitted into evidence. Finally, Family member Barbara

Hoyt was allowed to testify that she overheard Atkins say that Sharon

Tate was the last to die.

(2) Krenwinkel -- Through the testimony of Dianne

Lake, the jury was informed that Krenwinkel admitted she "had dragged

Abigail Folger from the bedroom to the living room."

(3) Van Houten -- Dianne Lake testified that Van

Houten told her that she had participated in the stabbing of a dead

body. The substance of the testimony implies that Van Houten

participated in the La Bianca murders.

The jury was instructed that these enumerated

admissions were admissible only as to each respective declarant.

With respect to co-appellants Krenwinkel and

Atkins, there is corroboration beyond their admissions and

declarations. Krenwinkel's fingerprint was found at the Tate

residence. As to her, that is sufficient corroboration by itself.

(People v. Ray (1962) 210 Cal. App. 2d 697, 703 [26 Cal.Rptr. 825].)

Discarded clothing found by a witness in the

vicinity of Cielo Drive fn. 31 was examined for blood and other

evidence. A chemist testified that not all the stains were capable of

interpretation; he was, however, able to positively identify the

stains on one item as human, blood type B. Folger, [61 Cal. App. 3d

149] Frykowski and Parent had blood type B. Human hair was found on

another of the items. Compared with Atkins' hair, testing showed

similarities in terms of color, length and medullary characteristic.

While the location of clothes with bloodstains in the vicinity of

Cielo Drive only substantiates Kasabian's testimony, the

identification of hair similar to Atkins' hair on that clothing

provides corroboration within the meaning of Penal Code section 1111

as to Atkins. The weight given to such evidence is for the jury. (See

People v. Carr (1972) 8 Cal. 3d 287, 292 [104 Cal.Rptr. 705, 502 P.2d

513]; 31 Am.Jur.2d, Expert and Opinion Testimony, § 129.)

Krenwinkel was ordered by the court to provide

exemplars of her handwriting. On the advice of counsel, she refused.

Evidence of her refusal was admitted against Krenwinkel. Obviously the

purpose of this procedure focused on the writings in blood at the

scenes of the homicides. fn. 32 The refusal to give a handwriting

exemplar tends to show a consciousness of guilt and is both

corroborative and independently probative. (People v. Hess (1970) 10

Cal. App. 3d 1071, 1076-1077 [90 Cal.Rptr. 268, 43 A.L.R.3d 643].)

Other evidence included the fact that Van Houten,

Krenwinkel and Atkins gave false names when they were arrested. [19]

The use of an alias is circumstantial evidence of consciousness of

guilt. [18b] It is therefore relevant and corroborative of Kasabian's

testimony. (People v. Perry (1972) 7 Cal. 3d 756, 775-776 [103

Cal.Rptr. 161, 499 P.2d 129]; People v. Olea (1971) 15 Cal. App. 3d

508, 515 [93 Cal.Rptr. 265]; Pen. Code, § 1127c.)

Krenwinkel also contends there is no corroborative

evidence to connect her with the commission of the La Bianca murders.

She erroneously presumes her implication in the Tate murders is not

corroborative within the meaning of Penal Code section 1111. The fact

[61 Cal. App. 3d 150] that these crimes occurred on successive dates

and in a significantly similar way is very probative. It is a

circumstance of corroborative nature properly considered by the trier

of fact. (People v. Robinson (1960) 184 Cal. App. 2d 69, 77 [7

Cal.Rptr. 202]; People v. Wilson (1926) 76 Cal.App. 688, 694-695 [245

P. 781].)

Aranda-Bruton

[20a] Relying on People v. Aranda (1965) 63 Cal. 2d

518 [47 Cal.Rptr. 353, 407 P.2d 265] and Bruton v. United States

(1968) 391 U.S. 123 [20 L.Ed.2d 476, 88 S.Ct. 1620], all appellants

assign error to the admission into evidence of the declarations of

Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten.

[21] When the prosecution is in possession of a

declaration inculpating not only the declarant but another

nondeclaring codefendant, Aranda commands an election from among three

procedures: (1) a severance of the nondeclarant codefendant to permit

him a separate trial; (2) editing a declaration to delete all matter

inculpating the nondeclarant; or, (3) exclusion of the entire

declaration if the case is to proceed as a joint trial and there is no

reasonable way to edit the declaration to delete the inculpating

material. Bruton expanded the Aranda holding to constitutional

dimensions.

[20b] When Atkins', Krenwinkel's and Van Houten's

admissions were offered, the court conducted evidentiary proceedings,

editing the admissions and eliminating references to co-appellants and

Watson. As submitted to the jury, the declarations read in the first

person.

After each admission the jury was instructed to

consider the admission only as to the particular declarant to whom it

was attributed. Consequently, we find no error in the procedure

followed. These admissions, the testimony of Linda Kasabian, and items

of physical evidence sufficiently and independently linked each

appellant to the commission of the crimes charged. That connection is

sufficient to discount any claim of error regarding admission of the

edited statements. We find no case suggesting "that it is Bruton or

Aranda error to admit in evidence the admission or confession of one

defendant, which reflects his commission of a crime that is revealed

by the physical evidence, because it might reflect on the issue of

whether or not a crime was actually committed by not only the

declarant but also by another, whom evidence, other than the

confession, links to the declarant's activities. In fact Aranda

suggests [61 Cal. App. 3d 151] the contrary. It suggests that if

references to the participation of anyone else, whether directly or

indirectly identified or not, are nonexistent, or are deleted, the

trial may be joint, and the extrajudicial statement may be received as

against the declarant ...." (People v. Epps (1973) 34 Cal. App. 3d

146, 157 [109 Cal.Rptr. 733]; see also, People v. Romo (1975) 47 Cal.

App. 3d 976, 984 [121 Cal.Rptr. 684].)

We recognize appellants' contention that the theory

of the prosecution is in large part dependent upon evidence pertaining

to the life style and communal organization of these people. In

opposing the introduction of the admissions, counsel for Krenwinkel

eloquently argued that to admit them would be highly prejudicial

because other evidence made it clear that these people ate together,

slept together, had sex together, and functioned as a unit so that

identification of one amounted to identification of all. This argument

misses the point.

The issue is whether or not the declaration of one

connects a nondeclarant to the crime in question. fn. 33 The problem

confronted by Aranda and Bruton is typically the case where the only

evidence linking the nondeclarant codefendant is the admission of his

accomplice. Here all appellants are linked to the crimes by the

testimony of Kasabian. Over and above Kasabian's testimony there is

the substantial corroborating evidence discussed above. Because each

admission was edited to delete any explicit reference to anyone other

than the declarant, none was made inadmissible by reason of

circumstantial implications that might be drawn by the jury. fn. 34

Concluding that introduction of the declarations of

appellants did not violate the mandate of Aranda or Bruton, we note

also that, in any event, if error did occur, it was harmless beyond a

reasonable doubt. (Brown v. United States (1973) 411 U.S. 223, 231 [36

L.Ed.2d 208, 215, 93 S.Ct. 1565]; Harrington v. California (1969) 395

U.S. 250 [23 L.Ed.2d 284, 89 S.Ct. 1726].) [61 Cal. App. 3d 152]

Sufficiency of the Evidence

The testimony of Kasabian and the evidence offered

in corroboration thereof, if believed by the jury, is sufficient to

support the verdicts of guilty as to each appellant. (People v.

Tewksbury (1976) 15 Cal. 3d 953, 962 [127 Cal.Rptr. 135, 544 P.2d

1335]; People v. Bynum (1971) 4 Cal. 3d 589, 599 [94 Cal.Rptr. 241,

483 P.2d 1193].)

Manson's assignment of error to the trial court's

denial of his motion made pursuant to Penal Code section 1118.1,

unsupported by argument or citation of authority, is frivolous.

Confidential Status of Incriminating Admission

[22] After her arrest Atkins was incarcerated at

Sybil Brand Institute. In accordance with regulations adopted and

enforced by the Los Angeles County Sheriff all incoming and outgoing

mail was opened, examined and censored. Four letters written by Atkins

thus came into respondent's possession; at trial, three were admitted

against her and they now form the basis of a contention that their

seizure was a violation of her rights under the First and Fourteenth

Amendments of the federal Constitution. Her contention is without

merit. fn. 35

The real issue raised by Atkins is not her surface

objection to censorship but rather that her mail was turned over to

the prosecuting authority in the present case, the District Attorney

of Los Angeles County. She suggests this constitutes an unlawful

seizure of evidence against her. Compelling authority demands a

contrary conclusion.

"'A man detained in jail cannot reasonably expect

to enjoy the privacy afforded to a person in free society. His lack of

privacy is a necessary adjunct to his imprisonment. ... Officials in

charge of prisoners awaiting trial may censor their mail, regulate

communications between them and outsiders and under certain

circumstances forbid communications between such prisoners and certain

classes of visitors. [Citations.]'" (People v. Dinkins (1966) 242 Cal.

App. 2d 892, 902-903 [52 Cal.Rptr. 134].) The majority of

jurisdictions permit the admission of mail authored by unconvicted

prisoners if it is obtained by means of routine mail censorship.

(Annot. Prisoners -- Censored Mail as [61 Cal. App. 3d 153] Evidence

52 A.L.R.3d 553.) Here the record supports a conclusion that the

aforementioned exhibits were lawfully obtained. They were therefore

properly admitted.

Kasabian's Testimony Irrelevant, Inherently

Improbable, Logically Irrelevant

[23] Manson asserts that Kasabian's testimony must

be disregarded on the grounds that it is irrelevant, inherently

improbable and logically ambiguous. This sweeping condemnation is made

even broader by reason of the numerous aspects of Kasabian's testimony

included in this categorical assignment of error. For the most part

Manson's complaint is best described as specious quibbling over

extrinsic and speculative issues. These assignments of error are

nothing more than conflicts in the evidence. Such conflicts are to be

resolved by the trier of fact. "The moral certainty which the law in

its humanity exacts before upholding the conviction of a man charged

with crime does not exclude every speculative and fanciful possibility

...." (People v. Ah Sun (1911) 160 Cal. 788, 791 [118 P. 240].)

Manson's assertion that Kasabian's testimony is

inherently improbable is without merit. Objections based on the theory

of inherent improbability place a substantial burden on the objector.

(People v. Thornton (1974) 11 Cal. 3d 738, 754 [114 Cal.Rptr. 467, 523

P.2d 267], cert. den., 420 U.S. 924 [43 L.Ed.2d 393, 95 S.Ct. 1118].)

Manson fails to meet that standard. Kasabian testified to nothing that

was physically impossible or false on its face. (See People v. Huston

(1943) 21 Cal. 2d 690, 693 [134 P.2d 758].)

The contentions of ambiguity and logical

irrelevancy are inapplicable. Manson invites us to discount all of

Kasabian's testimony by reading it without reference to the entire

record and by focusing on some conflicts in her descriptions. This we

cannot do. "Circumstances which, taken singly, seem to afford no

logical inference as to the issue, may when considered with other

circumstances give rise to such an inference. Thus the test of

relevancy must not be too strictly applied to a single question asked

of a witness or to any other single item of evidence. 'The theory upon

which evidence of circumstances is admitted ... is not that each

circumstance stands flawless in its proof of the ultimate fact, but

that each certain circumstance has a relation to and points reasonably

to the fact sought to be proved.'" (Witkin, Cal. Evidence (2d ed.

1966) § 313 (3), p. 276.) [61 Cal. App. 3d 154]

We have reviewed each of the items catalogued by

Manson as irrelevant, inherently improbable, ambiguous or logically

irrelevant. We totally disagree with his contentions and find them too

devoid of merit to justify particularized discussion of each one. fn.

36

Prejudicial Admission of Evidence

[24] On direct examination Kasabian was asked what

induced her to go to the Spahn ranch in the first place. In her answer

she referred to what she had been told by another member of the

commune, Catherine Louise Share, known as Gypsy. Kasabian testified

that Gypsy had "... told me that there was a beautiful man that we had

all been waiting for, and that he had been in jail for quite a number

of years ...." Manson's attorney objected and moved for a mistrial.

Although the motion was denied, the jury was

admonished "to disregard Mrs. Kasabian's remark about anybody having

spent any time in jail." Manson's claim of error is therefore

misplaced. Moreover, during cross-examination of Family member Brooks

Posten, Manson's attorney elicited testimony revealing that Manson had

a parole officer. Both the admonition and the allusion to

circumstances indicating his prior status as a convict purge

Kasabian's reference to jail of any prejudicial effect.

[25] A similar assignment of error is made by

Manson with respect to Kasabian's allusion to Manson's use of LSD. On

direct examination, and without objection, Brooks Posten testified to

an occasion when Manson was under the influence of Psilocybin. On

cross-examination, and without objection, Posten stated that Manson

favored LSD. Paul Watkins testified without objection to another

occasion when Manson was "... on an acid trip."

The occasions to which these witnesses referred

involved times when Manson alluded to himself as a Christ figure. This

self-characterization was a part of respondent's evidence in support

of its contention that Manson was the leader of the Family. Manson's

state of mind and his [61 Cal. App. 3d 155] appearance on these

occasions is therefore relevant. At the least it was germane to show

whether or not Manson's statements were consciously made or seriously

entertained. In any event, this testimony came in without objection

thereby foreclosing any claim of error on this appeal. (Evid. Code, §

353, subd. (a).) Furthermore, evidence elicited by all sides made it

perfectly clear that hallucinogenics were used at Spahn ranch.

Post La Bianca Homicide Conduct

[26] Complaining about Kasabian's testimony

concerning his statement directing Kasabian to kill an actor, Manson

contends it was inadmissible hearsay. fn. 37 According to Kasabian

this direction was given within hours after she, Manson, Atkins and

Grogan had retreated from the La Biancas' residence.

Disposition of this contention of error occurs when

the case of People v. Leach (1975) 15 Cal. 3d 419 [124 Cal.Rptr. 752,

541 P.2d 296] is contrasted to the case at bench. In Leach our Supreme

Court made clear the rule that extrajudicial declarations of a

coconspirator offered for the truth of the matters stated are

inadmissible if the declarations are made after the termination of the

conspiracy. Here the rule of Leach is inapplicable.

The conspiracy in which appellants were engaged was

broader than the substantive crime of murder. Circumstantial evidence

proves the overriding purpose of appellants and their coindictees--the

fomentation of the race war Manson characterized as Helter-Skelter.

Boundaries of a conspiracy are not limited by the substantive crimes

committed in furtherance of the agreement. fn. 38 [61 Cal. App. 3d

156]

Here the conspiracy amounted to fulfillment of

Manson's prophecy. The characterization of Helter Skelter as a

fanatical fantasy is of no consequence. (United States v. Bryant (N.D.

Tex. 1917) 245 F. 682, 684; Blumenthal v. United States (1947) 332

U.S. 539, 556-557 [92 L.Ed. 154, 167-168, 68 S.Ct. 248]; Perkins on

Criminal Law (2d ed. 1969) p. 635.) The gist of the conspiracy was the

comprehended common design, however bizarre and fanciful. It is not

necessary that the object of the conspiracy be carried out or

completed. (People v. Bedilion (1962) 206 Cal. App. 2d 262, 271 [24

Cal.Rptr. 19].) The corollary of that proposition is that the

conspiracy continues until it is accomplished or abandoned. It is

obvious that Helter Skelter was never realized and the conspiracy

remained pending. Leach is accordingly inapplicable -- the conspiracy

had not terminated.

We further distinguish Leach on the ground that

Manson's declarations were not offered for the truth of their

contents. Since the statements were not hearsay, the coconspirator

exception of Evidence Code section 1223 is inapplicable. Despite a

belief to the contrary by the trial court, relevance was not at all

dependent upon the truth of the matter stated. The relevancy of

Manson's orders to kill exists in the revelation of the nature of the

conspiracy. (People v. Lewis (1963) 222 Cal. App. 2d 136, 144 [35

Cal.Rptr. 1].) fn. 39

Evidentiary Implication of Gestures and

Self-Inflicted Marks

[27] Appellants were more than passive participants

in their trial. On numerous occasions they spoke out, interrupting the

proceeding by commenting and gesturing to each other and third

persons, including witnesses. As a result, the prosecution called

Detective Sergeant Manuel F. Gutierrez of the Los Angeles Police

Department. Testifying that he was in the courtroom during the trial,

Gutierrez described a specific incident observed by him. While

Kasabian was testifying Manson looked at her, "... took his right

index finger from right to left and made a motion across the bottom

[of] his chin from right to left." As described, it is not too

imaginative to characterize that conduct as a threat. fn. 40 [61 Cal.

App. 3d 157] Testimony establishing intimidation of a witness while

she is testifying is certainly relevant. (People v. Rosoto (1962) 58

Cal. 2d 304, 350 [23 Cal.Rptr. 779, 373 P.2d 867], cert. den., 372

U.S. 955 [9 L.Ed.2d 978, 83 S.Ct. 953]; People v. Teitelbaum (1958)

163 Cal. App. 2d 184, 216-217 [329 P.2d 157], cert. den., 359 U.S. 206

[3 L.Ed.2d 759, 79 S.Ct. 738]; Witkin Cal. Evidence 2d ed. (1974

Supp.) § 513, p. 417.)

Gutierrez also stated that he observed an "X" on

Manson's forehead and that, on the following day, he saw "X's" on the

foreheads of Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten. This behavior had some

tendency to show the affinity between the appellants as well as the

asserted leadership of Manson. It is not too speculative to presume

these decorations were observable by the jury. Testimony concerning

these markings could not be prejudicial and its admissibility was well

within the discretion of the trial court. (Evid. Code, § 352.) The