|

In the Court

of Criminal Appeals of Texas

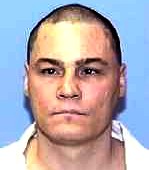

No. AP-74,344

RICHARD

ALLEN MASTERSON, Appellant

v.

THE STATE OF TEXAS

On

Direct Appeal From Harris County

Keller, P.J., delivered the

opinion of the unanimous Court.

O P I N I O N

Appellant was convicted of a capital murder

(1) committed on

January 27, 2001. Pursuant to the jury's answers to the special

issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article

37.071, ??2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge sentenced appellant to

death.

(2) Direct appeal

to this Court is automatic.

(3) Appellant

raises eight points of error. We will

affirm.

I. GUILT

A. Appellant's recorded confession

In points of

error two and three, appellant complains about the admission into

evidence of a tape-recorded confession taken from him by a Texas

police officer while appellant was in custody in Florida. In point

of error two, he complains that his confession was induced by a

promise of leniency for his nephew. In point of error three, he

complains that his confession was taken after he invoked his right

to counsel.

(4)

1. Background

After the

victim was murdered, appellant drove the victim's car to Georgia.

He left that car with relatives and continued on to Florida, where

he was arrested after stealing another car. In the meantime,

appellant's nephew was arrested for possession of cocaine left by

appellant in the victim's car.

Houston

police officer David Null interviewed appellant at the Marion

County, Florida jail. Null testified that he advised appellant of

all the warnings required by Article 38.22. After each warning, he

asked appellant whether he understood the warning, and appellant

answered affirmatively each time. Null then asked whether

appellant wished to give up those rights, and appellant stated

that "he wanted to clear things up." Null testified that he never

made any promises to appellant, never offered appellant anything

in exchange for talking about the murder case, and never

threatened appellant or any member of appellant's family.

Regarding appellant's nephew, Null testified that he was aware

that the nephew had been caught in a stolen car, but did not offer

anything to the nephew in exchange for a statement in the case.

Null said that appellant did say that there had been dope in the

car and that the dope belonged to appellant and not to the nephew.

When asked whether he offered to help the nephew in any way, Null

testified: "I told him [appellant] that if the dope was his and he

wanted to admit the dope was his that I would let the people know

that he was admitting that the dope, it was his dope." Null also

testified that appellant never asked for an attorney.

Appellant

testified that, when Null said he wanted to ask some questions, "I

asked him if I needed a lawyer." According to appellant, Null

ignored his question. Appellant also testified that he had earlier

asked a magistrate at extradition proceedings "if I could get a

lawyer." With regard to his nephew, appellant testified that he

told Null about his nephew's situation and asked "if they could

get that took care of." According to appellant, Null replied that

"he'd see what he could do." Appellant testified that he

understood that answer to mean "[t]hat he, if I cooperated with

him, he would help me out."

At the end

of the suppression hearing, the trial court found:

There is no

credible evidence to indicate that the defendant was ever promised

anything to make this statement. The credible evidence shows that

the defendant never asked for a lawyer, that he waived his rights

and freely and voluntarily gave the statement to Officer Null.

2. Analysis

In reviewing a trial court's ruling on a motion to suppress, the

appellate court should afford almost total deference to the trial

court's determination of the historical facts, especially when

that determination involves an evaluation of the credibility and

demeanor of witnesses.

(5) With respect

to both of appellant's claims, the trial court was free to believe

Officer Null's testimony and disbelieve appellant's testimony.

With regard to whether an impermissible promise was made, Officer

Null stated that he simply told appellant, if the drugs belonged

to him and he wanted to admit to that, Null would pass along that

admission. In Martinez v. State,

(6) we addressed

a similar situation. In that case, the police detective testified

that he told the defendant that he needed to know who the drugs

belonged to, and from that the defendant "could have gathered"

that his father and brother would not be charged if the defendant

"accepted responsibility."

(7) We held that

"the evidence supports the implied finding that no positive

promise was ever made by the detective" to the defendant.

(8) In the

present case, the police officer's statements were even more

circumspect because he simply indicated that he was willing to

pass along any information the defendant wanted to convey. No

positive promise was made. Moreover, the evidence suggests that

appellant initiated the discussion regarding helping his nephew. "Having

cast himself in the role of entrepreneur, [appellant] cannot

expect an appellate court to find implied 'promises' in official

responses (to his overtures) that are ambiguous at best."

(9)

Regarding appellant's claim that he requested counsel, the trial

court was within its discretion to believe Null's testimony that

no counsel was requested. Appellant contends, however, that the

trial court had no discretion to disbelieve appellant's testimony

about requesting counsel before the magistrate because the State

never controverted that testimony. But the trial court has

discretion to disbelieve testimony even if it is not controverted.

(10) The trial

court did in fact discount appellant's testimony and was within

its discretion to do so. Points of error two and three are

overruled.

B. Lesser-included offense

In point of

error one, appellant contends that the trial court erred in

refusing to submit his requested instruction regarding the lesser-included

offense of criminally negligent homicide. At trial, appellant

testified that he met the victim at a "hustler bar," went home

with him, and engaged in consensual sexual conduct with him.

According to appellant, the victim requested that appellant

perform a "sleeper hold" to enhance the quality of the victim's

sexual experience. Although the "sleeper hold" resulted in the

victim's death, appellant testified that this result was

unintended.

Assuming, without deciding, that appellant was entitled to the

requested instruction, we find any error to be harmless. The jury

was instructed on the lesser-included offense of manslaughter.

(11) We held in

Saunders v. State that the jury's failure to find an

intervening lesser-included offense (one that is between the

requested lesser offense and the offense charged) may, in

appropriate circumstances, render a failure to submit the

requested lesser offense harmless.

(12) This is so

because the harm from denying a lesser offense instruction stems

from the potential to place the jury in the dilemma of convicting

for a greater offense in which the jury has reasonable doubt or

releasing entirely from criminal liability a person the jury is

convinced is a wrongdoer.

(13) The

intervening lesser offense is an available compromise, giving the

jury the ability to hold the wrongdoer accountable without having

to find him guilty of the charged (greater) offense.

(14) While the

existence of an instruction regarding an intervening lesser

offense (such as manslaughter interposed between murder and

criminally negligent homicide) does not automatically foreclose

harm - because in some circmstances that intervening lesser

offense may be the least plausible theory under the evidence

(15) - a court

can conclude that the intervening offense instruction renders the

error harmless if the jury's rejection of that offense indicates

that the jury legitimately believed that the defendant was guilty

of the greater, charged offense.

(16)

In Saunders, the defendant was charged with murder by

squeezing a baby's head with intent to cause serious bodily injury.

(17) The trial

court denied the defendant's request to include in the jury charge

an instruction on criminally negligent homicide but did include an

instruction on "involuntary manslaughter"

(18) (now known

simply as "manslaughter").

(19) The basic

difference between (involuntary) manslaughter and criminally

negligent homicide was (and is) that "in the former, that actor

recognizes the risk of death and consciously disregards it, while

in the latter he is not, but ought to be, aware of the risk that

death will result from his conduct."

(20) We found

significant evidence in the record that the defendant was aware of

the risk of death,

(21) and

therefore, manslaughter was a realistic option for the jury.

(22) Consequently,

the jury's conviction of the defendant for murder, despite the

availability of involuntary manslaughter, indicated that the jury

did in fact believe that the defendant harbored the specific

intent required for the charged offense.

(23)

Like the

defendant in Saunders, appellant was denied an

instruction on criminally negligent homicide but received an

instruction on manslaughter. In addition, the record in the

present case also contains significant evidence of appellant's

awareness of the risk of death. On the witness stand, appellant

testified that he initially refused the victim's request to apply

a "sleeper hold" because doing so "scares" him. He testified that

he had performed such a hold before, and he testified that he knew

just by looking at the victim after he performed the "sleeper hold"

that the victim was dead. Under the circumstances, if the jury

truly believed that appellant performed a "sleeper hold" as a

sexual maneuver and did not intend to kill the victim, the jury

could easily have given effect to that belief by acquitting

appellant of capital murder and convicting him of manslaughter.

That the jury chose not to do so shows that it did not believe

appellant's story. We conclude that any error was harmless. Point

of error one is overruled.

II. PUNISHMENT

A. Sufficiency of the evidence - future dangerousness

In point of error five, appellant contends that the evidence is

legally insufficient to support the jury's answer to the "future

dangerousness" special issue

(24) because, due

to his testimony that he would attempt to commit criminal acts of

violence in the future, prison authorities would not allow him to

do so in prison and parole authorities would refuse to ever

authorize his release.

During

direct examination at the punishment phase of trial, appellant

testified:

[L]ike [the

prosecutor] told 'em from the beginning when they were picking the

jury, they have to answer two questions, am I going to be a future

danger? Am I going to protect myself by any means necessary? Yes I

am. That makes me a future danger, yes, I am. Second issue, is

there any mitigating circumstance. I don't think so. Everybody

lives and dies by the choices that they make. None of my family

out there could control what I did. I did what I did because I

wanted to do it, not because they made me do it, or because I got

my ass whooped. I got my ass whooped because I deserved it a lot

of times. Sometimes I got my ass whooped because I didn't deserve

it but most of the time I - I did something wrong, I got punished

for it. So whatever your decision is, I accept that. You found me

guilty, you must believe I'm guilty. And if you send me to prison,

for life, the chances are, in the Texas Department of Corrections

the chances are I'm going to have to defend myself, and like I

said, I will defend myself, whether it's against a guard or inmate

or anybody else by any means necessary. If that means a guard puts

his hands on me I'm going to put my hands on him. If a[n] inmate

comes up to me with a knife and tries to stab me, I'm going to

stab him or do whatever it takes to save my life from him.

Later, on

cross-examination, the following transpired:

Q. You

mentioned that you wanted - you think the jury should answer the

special issues in such a way that you get the death penalty, right?

A. If

they're following the law, yes.

Q. They have

to, right?

A. Yes, if

they're following the law, yes.

Q. Because

it's clear you're a future danger, right?

A. If it's -

if me protecting myself or my property, yes, I'm a future danger.

Q. And you

would do whatever it takes, be it hurt another inmate, hurt

another guard, to prove that, right?

A. Not

necessarily, but if that arises, yes I will, and I'm sure within

40 years, it will arise sometimes.

Q. You're

positive there's no way you could stay in prison probably even for

a year without getting violent again, right?

A. Probably

not. Probably not even a month.

In his brief,

appellant argues that the evidence clearly showed that he is a

danger to both prison and free society:

From the

evidence of the primary offense against Shane Honeycutt, the

offense against Steven and evidence at punishment about

Appellant's commission of threats and violence against others in

the free world, the jury must have drawn the conclusion that

Appellant presented a real danger, a threat to people in free

society. The testimony of jail personnel about Appellant's violent

conduct toward others in the county jail, including fighting with

other inmates and including verbal threats to one deputy, about

his membership in the Aryan Brotherhood gang (a gang which was

also present in the Texas prison system, according to a deputy

witness) and his readiness to defend the Brotherhood against "disrespect"

with violence. Together with Appellant's own testimony that he

would continue to commit criminal acts of violence in prison

whenever he deemed it necessary (which he told the prosecutor he

believed would probably occur "within a month") was certainly

evidence relevant to the jury's decision about the likelihood of

Appellant's being a continuing threat to prison society.

Appellant's feelings of remorse, or even regret, for any of his

violence toward others were remarkable for their absence; for

example, Officer Null, who took Appellant's tape recorded

statement, testified at guilt that Appellant told him that

Honeycutt's death "didn't really matter to him, he didn't feel any

remorse about it, he wasn't upset about it because he didn't know

him - and it just didn't matter." At punishment, Deputy Urick said

when he told Appellant in the jail that he would write him up for

refusal to follow Urick's order to pick up his food tray,

Appellant told him he would "choke you like I choke my victims."

In short, the evidence was strongly suggestive that Appellant

would be, and would strive to be a continuing threat both in

prison and in free society, were he ever to get there.

Appellant

argues that, given the obvious threat he poses, prison officials

would place him in lockdown to protect guards and other inmates

from him. In addition, appellant argues that the parole

authorities would never parole such a dangerous person. He

concludes that he does not in fact constitute a future danger

because the authorities will act to neutralize his ability to

threaten others.

Appellant's

argument appears to be that he is so dangerous that he is not

dangerous. His contention is ingenious but unpersuasive. If

accepted, it would stand the capital punishment scheme on its head,

giving relief to the most dangerous offenders. We will not

speculate, for legal sufficiency purposes, about the effectiveness

of the prison and parole authorities' methods of protecting

society from those who are intent on committing future criminal

acts of violence. Point of error five is overruled.

B. Order of closing argument

In point of

error four, appellant contends that the trial court erred in

refusing his request to give the concluding argument in punishment

on the mitigation special issue. Appellant contends that Article

36.07 does not govern capital cases, that the trial court has

discretion to change the order of arguments in a capital case,

that the State has no burden of proof on the mitigation issue and

any burden that does exist is on the defendant, and that his

constitutional rights were violated by the "psychological

advantage" the State had "in making the last impression on the

jury" in a death penalty case.

Article 36.07 provides: "The order of argument may be regulated by

the presiding judge; but the State's counsel shall have the right

to make the concluding address to the jury." Appellant contends

that Article 36.07 does not apply to capital cases. His only

reason for so concluding is the assertion that the procedure in

capital cases is controlled by Article 37.071, and that article is

silent as to the order of argument. However, the fact that Article

37.071 controls many aspects of capital punishment proceedings is

not, by itself, sufficient to reject the applicability of a

statute that, on its face, appears to apply to all criminal trials.

And in fact, we have previously held that Article 36.07 applies to

capital cases, including the punishment phase of a capital murder

trial.

(25) The State

suggests that Article 36.07 may be preempted by the following

sentence in Article 37.071: "The state and the defendant or

defendant's counsel shall be permitted to present argument for or

against a sentence of death."

(26) But that

provision covers only the content of argument: the parties are

permitted to explicitly argue for or against a "death sentence"

rather than simply arguing the special issues. That situation is

unique to death penalty cases, and thus, is understandably

included in Article 37.071. Nothing in the Code of Criminal

Procedure limits the application of Article 36.07 to non-capital

cases and we see no reason to do so.

Appellant argues that, in civil cases, the final argument falls to

the shoulders of whoever has the burden of proof. But we have held

that Article 36.07, not the civil rules, applies to criminal

cases.

(27) In

Martinez v. State, we rejected the defendant's claim that the

issue of insanity gave him the right to open and close argument,

even though insanity was the only contested issue in the case and

one on which the defendant carried the burden of proof.

(28) We held that

the trial court's refusal to permit the defendant to open and

close under those circumstances did not deprive the defendant of

any consititutional right.

(29) In a capital

case, we have likewise rejected a defendant's claim that a trial

court's failure to allow defense counsel to rebut the prosecutor's

arguments rendered his trial fundamentally unfair.

(30) We see

nothing about the mitigation special issue, which imposes a burden

of proof on neither party,

(31) that

distinguishes appellant's situation from our prior holdings. Point

of error four is overruled.

C. Constitutionality of the death penalty

1. Future dangerousness issue

In point of error six, appellant contends that the future

dangerousness issue is unconstitutional because the issue is not

susceptible to proof beyond a reasonable doubt and cannot be

applied fairly by the jury. He contends that a jury will tolerate

no risk in determining whether the defendant constitutes a future

danger to society. We have previously rejected this claim.

(32)

2. Failure to inform jurors of effect of hung jury

In points of error seven and eight, appellant contends that his

Eighth Amendment right against cruel and unusual punishments was

violated by the trial court's refusal to inform the jurors that a

failure to arrive at a unanimous verdict in favor of the State on

the punishment issues would result in a life sentence. He

acknowledges that the failure to so inform the jury is sanctioned

by statute and challenges the constitutionality of the part of

Article 37.071 that is often called the "12-10" rule. We have

previously rejected such arguments.

(33) Appellant

relies upon the dissent in Jones v. United States,

(34) but the

dissent is just that - a dissent. Relying upon the majority

opinion in Jones, we have recognized that the Supreme

Court has found that the Eighth Amendment does not require that

jurors be informed of the effect of a failure to reach unanimous

agreement on the punishment issues.

(35) Points of

error seven and eight are overruled.

The judgment

of the trial court is affirmed.

KELLER,

Presiding Judge

Date

delivered: February 2, 2005

Publish

*****

1. TEX. PEN. CODE ?19.03(a).

2. Art. 37.071, ?2(g).

Unless otherwise indicated, all references to Articles are to the

Texas Code of Criminal Procedure.

3. Art. 37.071, ?2(h).

4. Appellant argued these

two points of error together in his brief, and we address them

jointly here.

5. Maldonado v. State,

998 S.W.2d 239, 247 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999)(citing Guzman v.

State, 955 S.W.2d 85, 89 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997) and applying

its standard to a "promise" claim); Ripkowski v. State,

61 S.W.3d 378, 381-382 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001), cert. denied,

539 U.S. 916 (2003)(applying Guzman standard to

Miranda claims).

6. 127 S.W.3d 792 (Tex. Crim.

App. 2004).

7. Id. at 793.

8. Id. at 795.

9. Johnson v. State,

68 S.W.3d 644, 654-655 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002)(quoting

Henderson v. State, 962 S.W.2d 544, 564 (Tex. Crim. App.

1997), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 978 (1998))(bracketed

material inserted, other brackets deleted).

10. State v. Ross,

32 S.W.3d 853, 855 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000).

11. The jury was also

instructed on the lesser-included offenses of murder, robbery, and

aggravated assault.

12. 913 S.W.2d 564, 572 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1995).

13. Id.

14. Id.

15. Id. at 573.

16. Id. at 574.

17. Id. at 566.

18. Id. at 565-566.

19. See Acts 1993, 73rd

Leg., ch. 900, ?1.01.

20. Saunders, 913 S.W.2d at 565.

21. Id. at 573-574.

22. Id. at 573.

23. Id. at 574.

24. The issue asks: "whether

there is a probability that the defendant would commit criminal

acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to

society." Art. 37.071, ?2(b)(1).

25. Norris v. State,

902 S.W.2d 428, 442 (Tex. Crim. App.), cert. denied, 516

U.S. 890 (1995); see also Cherry v. State, 488 S.W.2d

744, 757 (Tex. Crim. App. 1972)(opinion on original submission),

cert. denied, 411 U.S. 909 (1973).

26. Art. 37.071, ?2(a)(1).

27. Martinez v. State,

501 S.W.2d 130, 131-132 (Tex. Crim. App. 1973), appeal dism'd,

415 U.S. 970 (1974); Brown v. State, 475 S.W.2d 938, 957

(Tex. Crim. App. 1971).

28. 501 S.W.2d at 132.

29. Id.

30. Norris, 902

S.W.2d at 442.

31. Escamilla v. State,

143 S.W.3d 814, 828 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004).

32. Resendiz v. State,

112 S.W.3d 541, 546 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003), cert. denied,

124 S. Ct. 2098 (2004).

33. Escamilla, 143

S.W.3d at 828; Busby v. State, 990 S.W.2d 263, 272 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1999), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1081 (2000).

34. 527 U.S. 373 (1999).

35. Resendiz, 112

S.W.3d at 549. |