|

In the Court of Criminal Appeals of

Texas

No. 74,936

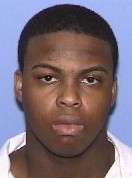

DAMON ROSHUN MATTHEWS, Appellant

v.

THE STATE OF TEXAS

ON DIRECT APPEAL

FROM HARRIS

COUNTY

Keller, P.J., delivered the

opinion of the unanimous Court.

O P I N I O N

Appellant was convicted in April 2004

of capital murder.

(1) Pursuant to

the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in Texas Code

of Criminal Procedure Article 37.071, §§ 2(b) and 2(e), the trial

judge sentenced appellant to death.

(2) Direct appeal

to this Court is automatic.

(3) Appellant

raises ten points of error. Finding no merit in

appellant's claims, we shall affirm.

I.

SUFFICIENCY OF THE EVIDENCE

A. Background

Viewed in

the light most favorable to the verdict, the evidence at trial

shows the following: Appellant and the victim, Esfandiar Gonzalez,

grew up together and had known each other since elementary school.

Gonzalez lived with his parents, worked full-time at a Kroger

grocery store, and had no criminal history.

On March 6,

2003, at around 6:50 p.m., Gonzalez drove his Oldsmobile to Kroger,

and picked up and cashed his paycheck for $211.61. Around 7:00

p.m., Gonzalez talked to appellant on the phone. Twenty minutes

later, Gonzalez called his mother and told her that he was going

with a friend to look at some speakers for his car.

Gonzalez

drove to a Super 8 motel in Sharpstown at around 9 p.m. and picked

up appellant, who was staying in room number 243. They drove to a

parking lot at 12400 Sharpview. While they were parked, Gonzalez

sat in the driver's seat of the car. Appellant got out of the car

and stood outside the front passenger side door. Appellant then

pointed a gun at Gonzalez through the half-opened passenger window

and shot him in the head seven times, killing him.

Blood

spatter evidence on Gonzalez's clothes and body indicated that

Gonzalez had been sitting in an upright position when he was shot

and that Gonzalez's body had been pulled out of the car and dumped

at the scene. Blood stains on appellant's shorts and spatterings

on the side of his tennis shoes were consistent with appellant

shooting Gonzalez while he sat in the driver's seat, pulling his

body out of the car, and tipping the body, causing blood to run

from his head. Blood stains on the shoulder seat strap of the

driver's seat of the Oldsmobile and high velocity specks on the

overhead liner were consistent with someone being shot at close

range while sitting in the driver's seat. The stains on the

passenger's seat were consistent with the passenger's door being

closed and the shooter leaning down and shooting through the

passenger's window.

Around 10

p.m., appellant drove Gonzalez's car to his motel room. Weirleis

Flax, who was staying in the same room, was there when appellant

came inside and changed his clothes and shoes. Appellant placed

his clothes and shoes in a pile and then left the motel.

Meanwhile,

Kalen Hutchenson, who lived in a house at 12400 Sharpview, heard a

cell phone ringing at around 9:30 p.m. and stepped outside to see

where the cell phone was. He discovered Gonzalez's body in the

parking lot. He took Gonzalez's cell phone and called 911, and

waited for the police to arrive. Officer Andrew Taravella and

Sergeant Hub Mayer arrived at the scene. They found no firearms

evidence - no shell casings or bullet strikes - in the

surroundings of the nearby buildings. In Gonzalez's pocket they

found a piece of paper with the number 243 on it and a dollar in

change. While they were investigating the scene, Gonzalez's cell

phone rang; the officers answered it. It was Caesar, Gonzalez's

brother. Upon talking to Caesar, the officers realized that

Gonzalez's car was missing from the scene, so they dispatched a

description of Gonzalez's Oldsmobile over the radio.

Around 1:00

a.m., Deputy David Mash was patrolling the area when a young male,

Javier Sasedo, approached him and told him that his friend had

been murdered a few hours earlier and that he had just seen

someone driving his friend's car into a do-it-yourself carwash on

Dashwood, about a block away. Mash notified dispatch and requested

assistance from back-up units. He then drove to the carwash and

saw appellant in one of the carwash stalls washing blood out of

Gonzalez's car. Mash apprehended appellant and put him in the back

seat of the patrol car. When back-up units arrived, the officers

took photographs of Gonzalez's car and looked into the driver's

side of the car. They saw that there was blood that started from

the driver's side and ran to the passenger's side. The officers

also recovered a gun, a Davis .380, from the floorboard of the

driver's side of Gonzalez's car, and they recovered a fired .380

shell casing in the back of the car. The gun was later determined

to be the murder weapon.

Around 2:00 a.m. at the scene, Mayer interviewed appellant and

taped the interview.

(4) In his oral

statement, appellant denied any involvement in Gonzalez's murder.

He said that a short Hispanic male, with a bald head and gold in

his mouth, named "Creeper,"

(5) came over to

the motel in Gonzalez's car and asked him if he wanted to "pimp

the car for a little bit."

At first, appellant claimed that he did not know that the car

belonged to Gonzalez. He said that he drove the car for a few

minutes, before he noticed the blood on his hands and on the car.

He then took the car to the carwash to wash out the blood. When

the police arrived, he denied any knowledge of the gun on the

floorboard. He stated that he never fired a weapon that night.

When asked about the identity of "Grumpy," a nickname of Gonzalez,

appellant said he did not know who Grumpy was. He later admitted

that Grumpy had called him earlier that day and that he had known

Grumpy since they were in school together.

After the

interview, Mayer went to the motel room at the Super 8. Flax

opened the door and consented to the entry and search of the room.

Flax indicated that appellant had come over, changed his clothes

and shoes, and left again. Appellant's clothes and shoes were

recovered from the room. Testing revealed that the clothes and

shoes recovered from the motel room and the clothes appellant wore

at the time of his arrest had Gonzalez's DNA on them.

Around 5:00 a.m., Police Officer Norman Ruland interviewed

appellant on video.

(6) In his

videotaped statement, appellant changed his story multiple times.

At first, appellant told Ruland that, around 7:00 p.m., Grumpy

picked up appellant and asked him where to get cocaine.

(7) Appellant

then took Gonzalez to see Creeper and a guy named "T-Man."

Appellant stayed in the car while Gonzalez talked to Creeper and

T-Man. According to appellant, before Gonzalez returned to Creeper,

he took appellant to the motel room that appellant shared with

Flax. Creeper then drove to the motel in Gonzalez's car and asked

appellant if he wanted a ride. Appellant took the car for a ride.

When he noticed the blood on his hands and clothing, he took the

car to the carwash.

After further questioning, appellant claimed that he heard gunfire

when Gonzalez, Creeper and T-Man were talking and he was sitting

in the car. According to appellant, Creeper shot at Gonzalez, and

Gonzalez shot at Creeper, and then Gonzalez went to the car,

shouted to appellant that he had set him up, and shot two or three

times at appellant. Everyone was outside the car at this time, and

appellant shot his gun, "a little .25," once in self-defense,

before he threw down his gun and ran back to the motel. He claimed

that he did not know that Gonzalez was dead or who shot Gonzalez.

He also claimed that he did not know that the car was full of

blood or who owned the gun on the floorboard, although he

speculated that the gun belonged to Creeper. Appellant later said

that Gonzalez and Creeper were members of the La Primera gang

(8) and therefore

friends. He admitted that it did not make sense that Creeper would

kill Gonzalez and take his car to appellant, a non-member of the

gang. He then recalled that it was an unknown black man, not

Creeper, who brought Gonzalez's car, full of blood, to him and

asked him if he wanted a ride. He then drove Gonzalez's car to the

carwash.

Dr. Ana

Lopez, assistant medical examiner at the Harris County Medical

Examiner's Office, performed an autopsy of Gonzalez's body on

March 7, 2003, and determined that he had six gunshot wounds on

the right side of his head, another gunshot wound on the top of

his head, a contusion on his shoulder and some abrasions on his

back. She concluded that two of the gunshot wounds were surrounded

by multiple stippling marks and no soot, indicating a proximity of

the gun to Gonzalez of approximately one to three feet. Five of

the bullets were recovered from the neck, suggesting that the

bullets traveled from the right side of his face to the left and

downward, consistent with an individual standing and shooting

downward to someone who is sitting. Six of the seven gunshot

wounds were characterized as fatal.

The record, viewed in a neutral light, reveals the following

evidence favorable to appellant. In both statements to the police,

appellant repeatedly denied killing Gonzalez. A fingerprint lifted

on the outside of the driver's door and submitted for latent

examination had insufficient characteristics to be identifiable.

No fingerprints were lifted from the .380 or the bullets. Dr. Eric

Sappenfield, a trace section supervisor for the Harris County

Medical Examiner's Office, analyzed samples submitted from

appellant's hands on March 6, 2003, for gunpowder residue under a

scanning electron microscope. The results were "inconclusive,"

meaning gunpowder residue was either not present or it could not

be determined whether it was present.

(9)

Finally, Lawrence Renner, a blood stain expert, determined that

the blood stain on appellant's sweatshirt was a transfer pattern

stain, caused by something with blood on it touching the surface

of the sweatshirt. There was no blood spatter on the sweatshirt,

though there should have been if appellant was wearing the

sweatshirt while shooting Gonzalez from one to three feet away.

(10)

B. Analysis

In points of error one and two, appellant contends that the

evidence is legally and factually insufficient to sustain his

conviction for capital murder. Evidence is legally insufficient if,

viewed in the light most favorable to the prosecution, no rational

jury could find the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

(11) Under a

factual sufficiency review, we consider all of the evidence in a

neutral light and ask whether the jury was rationally justified in

finding guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. There are two ways in

which the evidence may be factually insufficient.

(12) First, when

considered by itself, evidence supporting the verdict may be too

weak to support the finding of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

(13) Second,

there may be both evidence supporting the verdict and evidence

contrary to the verdict.

(14) If, in

weighing all the evidence under this balancing scale, the contrary

evidence is strong enough that the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt

standard could not have been met, the guilty verdict should not

stand.

(15) We find

appellant's claims of legal insufficiency and factual

insufficiency to be without merit.

Appellant

argues that the evidence is legally insufficient because: (1)

there was no direct evidence that appellant personally shot

Gonzalez; (2) appellant denied killing Gonzalez in his statements

to the police; and (3) the evidence supports the defense theory

that appellant merely moved Gonzalez's car or body, and such

evidence might implicate appellant as a party or would have

supported a conviction for theft or unauthorized use of a motor

vehicle.

In reviewing the legal sufficiency of the evidence, we look at the

events occurring before, during, and after the commission of the

offense.

(16)

Circumstantial evidence alone can be sufficient to establish guilt.

(17) Each fact

does not need to point directly and independently to the guilt of

the appellant as long as the cumulative effect of all the

incriminating facts are sufficient to support the conviction.

(18)

Viewing the

evidence in the light most favorable to the verdict, we find that

the evidence is legally sufficient to sustain the conviction of

capital murder. There was evidence that appellant and Gonzalez

talked on the phone. Gonzalez called his mother to tell her that

he was going with a friend to look for speakers for his car.

Appellant confessed that Gonzalez picked appellant up from a Super

8 motel in Sharpstown. Gonzalez later was found dead at a parking

lot on Sharpview; he had the number 243 on a piece of paper in his

pocket - the room number in which appellant was staying. Appellant

confessed that he drove Gonzalez's car to the motel room to change

out of his bloody clothes and shoes; DNA testing revealed that

these items had Gonzalez's DNA on them. Appellant then drove

Gonzalez's car to a car wash and attempted to wash all of the

blood out of the car, at which time he was apprehended by the

police. The murder weapon was recovered on the floorboard of

Gonzalez's car.

Appellant

gave the police two statements, in which he changed his story

multiple times. He ultimately stated that he was present at the

scene of the shooting and that he fired a shot and left the scene

in Gonzalez's car. The cumulative effect of all of these

incriminating facts are sufficient to support appellant's

conviction. Point of error one is overruled.

Appellant

argues that the evidence is factually insufficient because: (1)

appellant denied killing Gonzalez in his statements; (2) the

defense offered an alternative theory that Gonzalez was involved

in drugs and the La Primera gang and was killed by someone named "Creeper"

or some other unknown gang member; and (3) the defense presented

testimony by defense expert, Larry Renner, that contradicted the

State's blood-spatter expert testimony.

In reviewing the evidence for factual sufficiency, we do not "find"

facts or substitute our judgment for that of the fact finder.

(19) The jury is

the sole judge of the weight and credibility to be given to a

witness's testimony.

(20)

The jury could accept or reject any or all of the statements that

the appellant made in his tape-recorded and videotaped statements.

(21) Looking at

the evidence in a neutral light, we conclude that the jury was

rationally justified in finding guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,

and thus the evidence is factually sufficient to sustain the

conviction for capital murder. Point of error two is overruled.

II.

LESSER-INCLUDED OFFENSES

In points of

error three through five, appellant contends that the trial court

erred in refusing to submit his requested instruction regarding

the lesser-included offenses of theft and unauthorized use of a

vehicle. Point three raises a state-law claim while points four

and five allege violations of the Federal Constitution,

specifically the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

and the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual

punishment.

At the

conclusion of the evidence, appellant requested that the trial

court include instructions in the jury charge on murder, theft,

and unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. The trial court granted

defense counsel's request for a charge on murder but denied

appellant's request for charges on theft and unauthorized use of a

motor vehicle.

Under state law, a lesser-included offense must be included in the

jury charge if: (1) the requested charge is for a lesser-included

offense of the charged offense; and (2) there is some evidence

that, if the defendant is guilty, he is guilty only of the lesser

offense.

(22) In other

words, there must be some evidence from which a jury could

rationally acquit the defendant of the greater offense while

convicting him of the lesser-included offense.

(23)

To convict appellant of capital murder, the jury was required to

find beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant intentionally caused

the death of Esfandiar Gonzalez while in the course of committing

or attempting to commit robbery. Robbery is a lesser-included

offense of murder in the course of robbery. Theft is a lesser-included

offense of robbery.

(24) But

unauthorized use a motor vehicle is not a lesser-included offense

of the capital murder charged in this case, since it is not

included in the proof necessary to establish that the defendant

intentionally committed murder in the course of committing or

attempting to commit robbery.

(25) The trial

court therefore did not violate state law in denying appellant's

request for an instruction on unauthorized use of a motor vehicle.

Although theft is a lesser-included offense of robbery, there is

no evidence here that appellant is guilty only of the lesser-included

offense of theft. To be entitled to a jury instruction on the

lesser-included offense of theft, the record must contain evidence

that appellant committed a theft of the victim's property but did

not injure or threaten him and did not make him fearful of

imminent physical injury.

(26)

The evidence

shows that appellant admitted in his statements that he shot at

Gonzalez and took Gonzalez's car. There was no evidence from which

a jury could rationally acquit appellant of murder in the course

of robbery while convicting him of theft. Thus, the trial court

did not violate state law in refusing appellant's request that the

jury be instructed on the lesser-included offense of theft. Point

of error three is overruled.

With regard to the alleged violations of the

Federal Constitution, appellant has not shown that the trial

court's action in refusing appellant's requested instructions

denied appellant his due process rights or violated the

prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

(27)

Points of error four and five are overruled.

III. PUNISHMENT

In point of error six, appellant contends that

the assessment of the death penalty violated the Eighth Amendment

because of appellant's youth and because the jury's answers to the

special issues may have been based on conduct of appellant

occurring when he was seventeen years old or younger.

Appellant filed a pretrial motion to quash the

indictment and preclude the death penalty as a sentencing option

on the ground that § 8.07(c)

(28) of the Texas

Penal Code violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the

United States Constitution. After the State rested in the guilt

phase of trial, appellant argued the motion and specifically

argued that Roper v. Simmons

(29) was before

the United States Supreme Court and that the Court would be

deciding whether to uphold the imposition of the death penalty on

persons seventeen years old or under. As appellant was eighteen

years old at the time of the offense, the trial court denied the

motion.

The United States Supreme Court held in

Simmons that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution "forbid imposition of the death penalty

on offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were

committed."

(30) Because

appellant was eighteen years old when he committed the offense of

capital murder, the holding in Simmons does not apply,

and, therefore, the assessment of the death penalty in this case

did not violate the Eighth Amendment of the United States

Constitution.

Appellant also asserts that the admission of

evidence in the punishment phase of prior bad acts and prior

offenses he committed while he was under the age of eighteen was

unconstitutional. However, appellant did not object to the

admission of the evidence

(31) at trial on

this basis.

To preserve error for appellate review, the

complaining party must make a timely, specific objection and

obtain a ruling on the objection.

(32) The failure

to make an objection at trial on the grounds complained of on

appeal forfeits many claims, including an Eighth Amendment claim

of cruel and unusual punishment.

(33) Appellant

forfeited his complaint that admission of evidence of prior bad

acts and prior offenses committed as a juvenile violated the

Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Moreover, appellant's complaint is without

merit. Article 37.071 permits the admission of evidence at the

punishment phase of capital cases regarding "any matter that the

court deems relevant to sentence, including evidence of the

defendant's background or character. . . ."

(34) Youth is

neither a mitigating

(35) nor an

aggravating factor as a matter of law; rather, the jurors

interpret the facts and determine if youth is a mitigating or

aggravating factor, or neither.

(36)

In the punishment phase of a capital murder

trial, the admission of prior offenses committed when the

defendant was a juvenile does not violate the Eighth Amendment if

he was assessed the death penalty for a charged offense that

occurred when he was at least eighteen years old.

(37) Appellant

was assessed the death penalty for the charged offense of capital

murder, which he committed when he was eighteen years old. Point

of error six is overruled.

In points of error seven and eight, appellant

contends that the trial court erred in failing to instruct the

jury that the State has the burden of proof beyond a reasonable

doubt on the mitigation issue. He argues that the Texas statute

(38) is

inconsistent with Apprendi v. New Jersey

(39) and its

progeny and with the Texas constitutional guarantee of due course

of law. Appellant filed a proposed jury charge

(40) regarding

the mitigation issue, and the trial court denied the request. The

Apprendi and Blakely claims have been raised and

rejected.

(41)

Appellant also relies on United States v.

Booker.

(42) He claims

that Article 37.071 is a guidelines-type statute that differs from

the Federal Sentencing Guidelines in degree rather than in kind.

In Booker, the Court held that the

Sixth Amendment requirement that any fact, other than a prior

conviction, which is necessary to support a sentence exceeding the

maximum authorized by the facts established by a plea of guilty or

a jury verdict must be admitted by the defendant or proved to a

jury beyond a reasonable doubt was incompatible with the Federal

Sentencing Act, which called for promulgation of mandatory federal

sentencing guidelines; thus, provisions of the Act that made

guidelines mandatory and set forth the standard of review on

appeal would be severed and excised.

(43) The Supreme

Court also reaffirmed its holding in Apprendi that any

fact, other than a prior conviction, which is necessary to support

a sentence exceeding the maximum authorized by the facts

established by a plea of guilty or a jury verdict, must be

admitted by the defendant or proved to a jury beyond a reasonable

doubt.

(44) We have held

that Article 37.071 satisfies these requirements.

(45) Points of

error seven and eight are overruled.

In point of error nine, appellant contends that

the trial court erred in failing to instruct the jury that the

State has the burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt on the

mitigation issue because the Texas statute gives the jury "mixed

signals" as to how the mitigation issue is to be applied.

At trial, appellant requested an instruction on

the State's burden of proof on the mitigation issue, based on

Penry v. Johnson,

(46) because

without this instruction, the mitigation issue gives the jury, at

best, mixed signals as to how the jury is to go about answering

the issue. The trial court denied the request. Appellant claims

that the Texas death penalty statute violates the Eighth Amendment,

as interpreted in Penry II, because, in that it is

unclear as to the burden of proof, the mitigation instruction

suffers from the same constitutional flaw of sending "mixed

signals" to the jury. We have rejected the argument that the

mitigation issue sends "mixed signals" to the jury, and we have

rejected the argument that the failure to assign a burden of proof

violates the Eighth Amendment.

(47) Point of

error nine is overruled.

In point of error ten, appellant contends that

the punishment charge misinformed the jury by failing to disclose

that each juror could prevent a death sentence by disagreeing with

the other jurors, in violation of the heightened reliability

requirement of the Eighth Amendment of the United States

Constitution and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. We have decided these claims adversely to this position.

(48) Point of

error ten is overruled.

The judgment of the trial court is affirmed.

Keller, Presiding Judge

Date delivered: June 28, 2006

Do Not Publish

*****

1. Tex. Penal Code Ann.

§19.03(a).

2. Article 37.071, § 2(g).

Unless otherwise indicated all future references to Articles refer

to Code of Criminal Procedure.

3. Article 37.071, § 2(h).

4. Before appellant gave his

tape-recorded oral statement, Mayer read appellant his statutory

rights, and appellant stated that he understood them and that he

knowingly and voluntarily waived them. A redacted recording was

admitted at trial without objection.

5. Appellant used the names

"Creeper" and "Creepy" interchangeably in his statements.

Subsequent to appellant's statement, Mayer interviewed "Creeper,"

named Froylan Bettencourt, a tall Hispanic male without gold in

his mouth. Bettencourt stated that he was not present on the night

of March 6, 2003, and he was not the shooter. He was eliminated by

Mayer as a suspect.

6. Ruland read appellant his

statutory rights, and appellant voluntarily waived those rights

and gave a videotaped statement. The tape was admitted at trial.

7. A postmortem toxicology

examination revealed that there was no cocaine or any other type

of drug or alcohol in Gonzalez's blood.

8. At trial, the defense

suggested that Gonzalez's death was tied to his membership in the

La Primera gang. The defense presented testimony by Dwight Stewart,

a training specialist for the Texas School Safety Center and

instructor of gang awareness, that Gonzalez had tattoos on his

body signifying that he was a member of La Primera. However,

Officer Ruland, who had worked in the divisional gang unit of the

Houston Police Department, testified for the State that none of

the tattoos found on Gonzalez's body signified that he was a

member of the La Primera gang. Caesar Gonzalez also testified that

his brother was not in a gang. And Kim Whitehead, assistant

principal and gang education awareness representative at

Gonzalez's school, testified that, after counseling Gonzalez, she

determined that, because he wore white and had friends in the gang,

Gonzalez at a prior time may have been associated with the La

Primera gang, but his tattoos did not indicate that he was in a

gang.

9. Dr. Sappenfield stated on

cross-examination that he would not expect to find gunshot residue

on the hands of a person who used a power sprayer to spray out a

car at a carwash because the person's hands would get wet and wash

the particles away from the hands.

10. Renner admitted on

cross-examination that the variables of wind, air-conditioning,

and the smaller caliber of a gun affect whether blood spatter will

reach the clothing of a shooter standing one to three feet away

from the victim.

11. Jackson v. Virginia,

443 U.S. 307, 319 (1979).

12. Zuniga v. State,

144 S.W.3d 477, 484 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004).

13. Id.

14. Id.

15. See id. at

485.

16. See Guevara v.

State, 152 S.W.3d 45, 49 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999).

17. See id.

18. See id.

19. See Zuniga,

144 S.W.3d at 482.

20. See Cain v. State,

958 S.W.2d 404, 407 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997).

21. See id.

22. See Hayward v.

State, 158 S.W.3d 476, 478 (Tex. Crim. App. 2005);

Rousseau v. State, 855 S.W.2d 666, 672 (Tex. Crim. App.

1993).

23. Moore v. State,

969 S.W.2d 4, 8 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998).

24. Tex. Penal Code Ann. §

29.02.

25. Tex. Penal Code Ann. §

31.07; see also Rousseau, 855 S.W.2d at 673.

26. Tex. Penal Code Ann. §

31.03(a).

27. See Wesbrook v.

State, 29 S.W.3d 103, 112-13 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000). In

Wesbrook, this Court rejected appellant's argument that the

trial court erred in failing to declare the Texas death penalty

statute unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

Appellant claimed that he was denied due process and equal

protection and was subjected to cruel and unusual punishment

because, at both the guilt and punishment phases, he was prevented

from submitting special instructions to the jury on the issue of

sudden passion arising out of adequate cause. This Court rejected

his claim because, inter alia, he failed to explain how

he was denied due process or subjected to cruel and unusual

punishment, and the Court could discern no indications that the

refusal to instruct the jury on sudden passion constituted cruel

and unusual punishment.

28. Section 8.07(c), at the

time of the offense, provided that, "No person may, in any case,

be punished by death for an offense committed while he was younger

than 17 years." Texas Penal Code

§ 8.07(c) (Vernon 2003). The amendment to § 8.07(c), made in

response to Simmons, applies to offenses occurring on or

after September 1, 2005; it provides that, "No person may, in any

case, be punished by death for an offense committed while he was

younger than 18 years."

29. 543 U.S. 551 (2005).

30. Id. at 578.

31. The State offered and

the trial court admitted: appellant's school records, reflecting

numerous school violations and suspensions; judgments in which

courts found appellant engaged in delinquent conduct for

possession of marijuana and carrying a handgun; appellant's

juvenile probation records, revealing numerous probation

violations; an order certifying appellant as an adult for

prosecution of two aggravated robberies; testimony by the two

victims of the aggravated robberies; and, testimony by officers

regarding appellant's arrest in the aggravated robberies.

32. Tex. R. App. P.

33.1(a).

33. Curry v. State,

910 S.W.2d 490, 497 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995).

34. Article 37.071 §

2(a)(1).

35. Under Article 37.071, §

2(f)(4), mitigating evidence is "evidence that a juror might

regard as reducing the defendant's moral blameworthiness."

36. See Moore v. State,

999 S.W.2d 385, 406 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999).

37. See Corwin v. State,

870 S.W.2d 23 (Tex. Crim. App. 1993).

38. Article 37.071, §

2(e)(1), requiring the mitigation special issue to be submitted to

the jury, asks: "Whether, taking into consideration all of the

evidence, including the circumstances of the offense, the

defendant's character and background, and the personal moral

culpability of the defendant, there is a sufficient mitigating

circumstance or circumstances to warrant that a sentence of life

imprisonment without parole rather than a death sentence be

imposed."

39. 530 U.S. 466 (2000).

40. Appellant's proposed

jury charge provided:

Regarding the comparison of mitigating evidence

and aggravating evidence, the State has the ultimate burden of

proof to convince you, beyond a reasonable doubt, that any

mitigating considerations are not sufficient to justify a sentence

of life imprisonment rather than the death penalty. This does not

mean that the State must negate any possible mitigating

consideration, whether or not it is raised by evidence. Rather,

the special issue asks you to make a comparative judgment between

factors on either side of the question which actually have been

raised by some evidence. If, after a thorough review of the

evidence on both sides of the question, you believe that there are

sufficient mitigating considerations, or you have a reasonable

doubt as to how to resolve the comparison which you must make

under the special issue, then you should answer this special issue

affirmatively.

41. See Woods v. State,

152 S.W.3d 105, 120 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004); Hankins v.

State, 132 S.W.3d 380 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004); Rayford v.

State, 125 S.W.3d 521, 533-34 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003);

Resendiz v. State, 112 S.W.3d 541, 549-50 (Tex. Crim. App.

2003), cert. denied, 541 U.S. 1032 (2004).

42. 543 U.S. 220 (2005).

43. Id. at 245.

44. See id. at

244-45.

45. See Woods, 152

S.W.3d at 120.

46. ("Penry II"),

532 U.S. 782 (2001) (holding that a court-made "nullification

instruction"-a jury instruction to nullify what would otherwise be

a factually correct determination that a defendant would probably

be dangerous in the future-was unconstitutional in that it sent "mixed

signals" to the jury).

47. See Perry v. State,

158 S.W.3d 438, 449 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004) (holding "[t]he

mitigation special issue does not send 'mixed signals' because it

permits a capital sentencing jury to give effect to mitigating

evidence in every conceivable manner in which the evidence might

be relevant"); see also Woods, 152 S.W.3d at

121-22; Scheanette v. State, 144 S.W.3d 503, 506 (Tex.

Crim. App. 2004); Escamilla v. State, 143 S.W.3d 814, 828

(Tex. Crim. App. 2004) (the mitigation issue is constitutional

despite its failure to assign a burden of proof); Jones v.

State, 119 S.W.3d 766, 790 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003), cert.

denied, 542 U.S. 905 (2004).

48. See Busby v. State,

990 S.W.2d 263, 272 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) (Eighth Amendment);

Moore v. State, 935 S.W.2d 124, 128-29 (Tex. Crim. App.

1996)(due process); see also Patrick v. State, 906 S.W.2d

481, 494 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995) (same).

|