|

185 F.3d 244

(5th Cir. 1999)

BOBBY JAMES MOORE,

Petitioner-Appellee,

v.

GARY L. JOHNSON, DIRECTOR, TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE,

INSTITUTIONAL DIVISION, Respondent-Appellant.

No. 95-20871

UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Oct. 27, 1999

Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Texas

ON REMAND FROM THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES

Before SMITH, EMILIO M. GARZA,

and DeMOSS, Circuit Judges.

DeMOSS, Circuit Judge:

The Director of

the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Institutional Division

appeals from the district court's final judgment granting Bobby

James Moore's petition for habeas corpus relief from his capital

sentence and remanding to the state court for a new punishment

hearing. We

affirm, as modified by this opinion, and remand with

instructions.

I.

The district court's decision

in this matter left the state trial court's judgment of guilt

intact, but granted relief as to punishment only by reversing

that portion of the state trial court's judgment imposing the

death penalty and remanding to the state trial court for a new

punishment hearing. This is the second time we have been asked

to review that decision. Our first decision followed this

Circuit's then-existing precedent by applying newly- enacted

provisions of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act

of 1996 (AEDPA) to Moore's petition, which was pending on the

April 24, 1996 effective date of AEDPA. See Moore v. Johnson,

101 F.3d 1069 (5th Cir. 1996), vacated, 117 S. Ct. 2504 (1997).

In that decision, we concluded that the district court failed to

afford the state habeas court's fact findings the deference

required by AEDPA's stringent standard of review. See Moore, 101

F.3d at 1076; see also 28 U.S.C. 2254(d) (providing that the

Court may not grant habeas relief with respect to any claim that

was adjudicated on the merits in a state court proceeding unless

that adjudication "resulted in a decision that was contrary to,

or involved an unreasonableapplication of, clearly established

Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United

States").

Shortly after our decision,

the Supreme Court decided Lindh v. Murphy, 117 S. Ct. 2059

(1997). Lindh holds that the provisions of AEDPA relevant to

this appeal do not apply to habeas corpus petitions that, like

Moore's, were pending as of the April 24, 1996 effective date of

AEDPA. Lindh, 117 S. Ct. at 2068. Lindh overrules this Circuit's

pre-Lindh precedent, which held that AEDPA applied to habeas

claims pending at the time AEDPA became effective. See, e.g.,

Drinkard v. Johnson, 97 F.3d 751 (5th Cir. 1996); see also

United States v. Carter, 117 F.3d 262 (5th Cir. 1997) (recognizing

that Lindh overruled Drinkard and its progeny).

After our initial decision,

Moore petitioned for and the Supreme Court granted a writ of

certiorari, remanding the case to our Court for reconsideration

in light of Lindh and the more lenient standards of review

applicable under pre-AEDPA law.

See 28 U.S.C. 2254(d) (1994) (providing that state habeas court

fact findings are entitled to a presumption of correctness, but

permitting a federal court to reject state habeas court fact

findings that are "not fairly supported by the record"). Having

concluded a thorough re-examination of the record, we find that

the district court's judgment is correct when examined in light

of the pre-AEDPA law applied therein. We therefore affirm the

judgment of the district court as modified by this opinion.

II.

The single issue before the

Court for resolution is whether Moore was deprived of his Sixth

Amendment right to effective assistance of trial counsel during

his 1980 capital trial. Moore claims that trial counsel were

constitutionally deficient in their pretrial investigation of

and presentation of a false alibi defense, and in their failure

to investigate, develop, or present mitigating evidence during

the guilt or punishment phase of his capital trial. Moore's

ineffective assistance of counsel claim is governed by the

familiar Strickland standard:

First, the defendant must show

that counsel's performance was deficient. This requires showing

that counsel made errors so serious that counsel was not

functioning as the "counsel" guaranteed the defendant by the

Sixth Amendment. Second, the defendant must show that the

deficient performance prejudiced the defense. This requires

showing thatcounsel's errors were so serious as to deprive the

defendant of a fair trial, a trial whose result is reliable.

Unless a defendant can make both showings, it cannot be said

that the conviction or death sentence resulted from a breakdown

in the adversary process that renders the result unreliable.

Strickland v. Washington, 104

S. Ct. 2052, 2064 (1984).

"Judicial scrutiny of

counsel's performance must be highly deferential." Id. at 2065.

We therefore indulge a strong presumption that strategic or

tactical decisions made after an adequate investigation fall

within the wide range of objectively reasonable professional

assistance. Id. at 2065-66. Such decisions are "virtually

unchallengeable" and cannot be made the basis of relief on a

Sixth Amendment claim absent a showing that the decision was

unreasonable as a matter of law. See id. at 2066; Loyd v.

Whitley, 977 F.2d 149, 157 (5th Cir. 1992); Wilson v. Butler,

813 F.2d 664, 672 (5th Cir. 1987). Strategic choices made after

less than complete investigation are reasonable only to the

extent that reasonable professional judgments support the

limitations on investigation. Strickland, 104 S. Ct. at 2066;

Whitley, 977 F.2d at 157-58.

The district court concluded

that Moore's counsel rendered constitutionally deficient

performance at both the guilt and punishment phases of his trial,

but found prejudice, and therefore granted relief, as to Moore's

capital sentence only. The district court's decision is premised

upon subsidiary findings that trial counsel were deficient in

the two major areas identified by Moore. First, the district

court found that counsel, in their presentation of an illogical

and incredible alibi defense: (1) conducted an inadequate

pretrial investigation, (2) ignored or excluded evidence that

the offense was accidental, rather than intentional, (3)

suborned perjury, and (4) elicited unduly damaging testimony

against Moore on cross-examination of a state witness. Second,

the district court found that counsel completely failed to

investigate, develop, or offer available mitigating evidence,

including previously redacted and exculpatory portions of

Moore's purported confession, during the punishment phase

ofMoore's capital trial.

On appeal, the Director

maintains that the district court impermissibly substituted its

own de novo view of the state court record for binding state

habeas court fact findings, thus failing to afford those fact

findings the presumption of correctness required by the pre-AEDPA

version of 28 U.S.C. 2254(d). With respect to deficient

performance, the Director maintains that both the decision to

pursue an alibi defense and the decision not to present

mitigating evidence were strategic decisions that are entitled

to deference under Strickland. With respect to prejudice, the

Director maintains that Moore cannot establish prejudice during

the punishment phase of his trial on the basis of deficient

performance during the guilt phase of his trial. Thus, the

Director maintains that deficient performance arising from

presentation of the alibi defense may not be imputed to the

punishment phase of Moore's trial. The Director further argues

that admission of the mitigating evidence proposed by Moore

wouldnot have affected the jury's decision to impose the death

penalty. Finally, the Director argues that the district court

exceeded its authority by remanding with instructions that the

state court conduct a new punishment hearing.

Moore responds that the

district court complied with 28 U.S.C. 2254(d) by affording any

relevant state habeas court fact findings the deference

justified by the record in this case. See 28 U.S.C. 2254(d)(8)

(1994) (providing that the federal court may, after a review of

the relevant record, reject state habeas court fact findings

that are "not fairly supported by the record"). Moore further

responds that the record reflects counsel did not make fully

informed strategic decisions with regardto the presentation of

the alibi defense or the failure to present mitigating evidence.

To the contrary, Moore responds that counsel failed to properly

investigate the controlling facts and law, both as to guilt and

as to punishment, with the effect that available and availing

evidence was never developed. Moreover, Moore responds that

counsel's decision to exclude the potentially exculpatory

evidence that was developed was both professionally unreasonable

and based upon an erroneous understanding of the controlling

legal principles. Thus, Moore maintains that there are no

reasonable strategic decisions entitled to this Court's

deference under Strickland. With respect to prejudice, Moore

maintains that there is a reasonable probability that, but for

counsel's deficient performance at both the guilt and punishment

phases of his capital trial, the jury would have reached a

different decision with respect to the appropriate sentence in

his case. Accordingly, Moore argues in support of the district

court's determinations that trial counsel were ineffective in

their pretrial investigation and presentation of the alibi

defense, and in their failure to investigate, develop or present

mitigating evidence during the punishment phase of Moore's trial.

Significantly, Moore has not

cross-appealed. We are therefore limited to a review of the

district court's decision that there is a reasonable probability

that but for counsel's deficient performance at either the guilt

phase or the punishment phase or both, Moore would not have been

sentenced to death. Given the absence of a cross-appeal, the

district court's decision that Moore failed to demonstrate

prejudice as to the guilt phase of his capital trial is not

before this Court for review, and we are not at liberty to

expand upon the relief granted by the district court. See United

States v. Coscarelli, 149 F.3d 342 (5th Cir. 1998) (en banc).

Having reviewed the record and

the arguments of the parties we affirm, with some modifications,

the district court's determination that counsel's performance

was deficient during the guilt phase of Moore's trial. We

likewise affirm the district court's determination that

counsel's failure to investigate, develop or present mitigating

evidence including exculpatory evidence that the offense was

accidental, during either phase of Moore's capital trial,

constituted constitutionally deficient performance that

prejudiced the outcome of the punishment phase of Moore's trial.

Accordingly, we affirm the district court's grant of relief.

We agree, however, with the

Director that the district court exceeded its authority by

ordering the state court of conviction to conduct a new

punishment hearing. The decision whether to pursue a new

punishment hearing pursuant to Texas Code of Criminal Procedure

article 44.29(c) is vested with the state court of conviction.

We therefore remand for entry of an order granting the writ of

habeas corpus, but permitting the state court of conviction a

reasonable time in which to cure the constitutional error by

imposing a sentence of less than death or conducting a new

punishment hearing as authorized by Texas state law.

III.

Moore's case has been pending,

in one court or another, for almost twenty years. An extensive

review of the various proceedings, including the evidence

adduced at Moore's trial, is essential to an understanding of

our disposition.

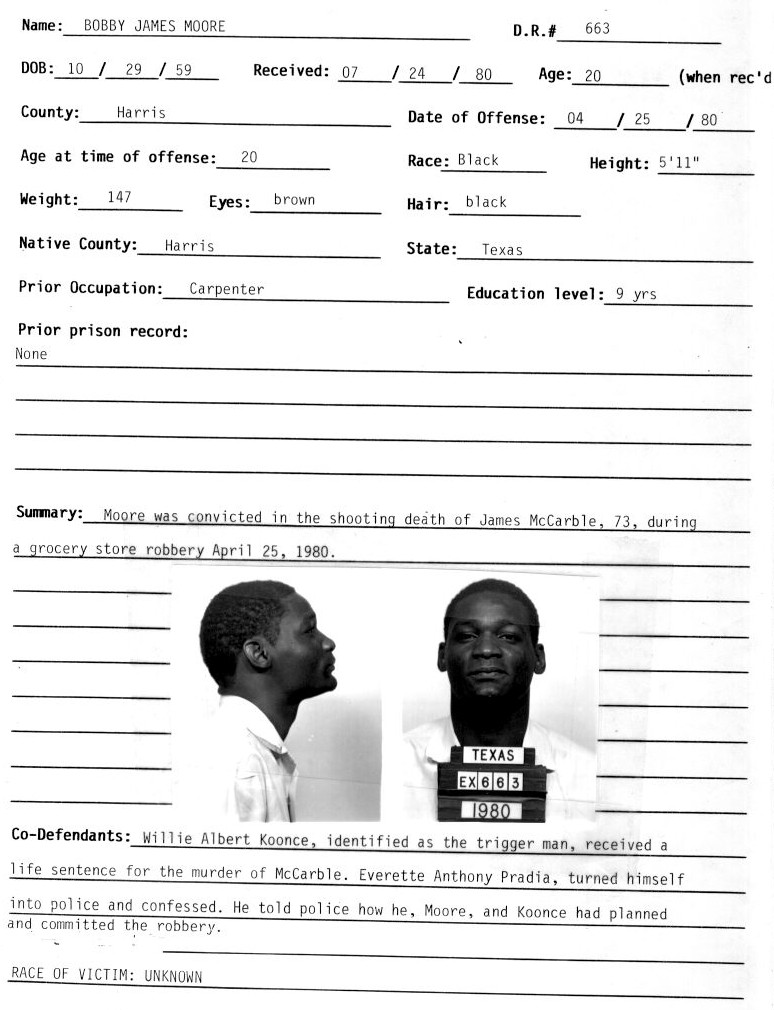

A. The Offense

Moore was convicted of capital

murder for the death of Jim McCarble, which was committed in the

course of a bungled robbery of the Birdsall Super Market in

Houston, Texas on April 25, 1980. On that day, McCarble and his

fellow employee Edna Scott were working in the courtesy booth at

the front of the store. Arthur Moreno and Debra Salazar were

checking groceries at nearby registers. Three men, later

identified as Willie "Rick" Koonce, Everett Anthony Pradia, and

petitioner Moore, entered the store. Koonce, who was identified

in pretrial line-ups and at trial by several witnesses, entered

the courtesy booth with a white cloth bank bag and ordered

McCarble to "[f]ill it up, man. You being robbed." McCarble then

jumped to the left of Scott, which allowed Scott to see a second

man, later identified as Moore, standing outside the courtesy

booth and pointing a shotgun in her direction. The man holding

the shotgun was wearing a wig and sunglasses, which together

with the shotgun, obscured part of his face. The shotgun itself

was partially wrapped in two plastic bags. Neither Scott nor

Moreno nor Salazar was able to positively identify Moore as the

man holding the shotgun at either the pretrial line-up or at

trial. Scott testified that the man with the shotgun must have

been significantly taller than herself because she was able to

look directly into his eyes, notwithstanding the fact that she

wasstanding on the floor of the elevated courtesy booth. At

trial, it was demonstrated that Moore was approximately the same

height, if not slightly shorter, than Scott. Salazar's testimony

on the issue of identity was the strongest. Salazar initially

testified that she was certain that Moore was the man pointing

the shotgun into the courtesy booth. But Salazar later qualified

her testimony by stating that she was not certain and could be

mistaken. Leonard Goldfield, the manager of the Birdsall Super

Market, testified that he only saw two men whom he suspected of

participating in the robbery. Goldfield positively identified

those two men as Koonce and Pradia.

When Scott observed the man

with the shotgun, she shouted to the assistant manager that

there was a robbery in progress and then dropped to the floor of

the courtesy booth. Pradia, sensing that the robbery was going

wrong, fled the store. Moreno and Salazar testified that they

observed the man with the wig rise up on his toes and aim the

shotgun down into the courtesy booth. Scott testified that she

heard the shotgun discharge and observed McCarble, who sustained

a fatal wound to the head, fall to the floor beside her.

Koonce and Moore fled the

store. On the way to the car, Moore dropped one of the plastic

bags covering the gun and the wig he was wearing. Store customer

Wulfrido Cazares observed the three robbers get into a red and

white car and made a mental note of the license plate number.

Cazares had the letters memorized, but had two alternative

configurations for the numerical portion of the license plate.

When those numbers were later given to the police, one of the

numbers was registered to a red and white Mercury Cougar

belonging to Koonce.

B. The Investigation

The plastic bag and wig

dropped by the shooter were later recovered from outside the

store by police. Police also recovered a second plastic bag that

was left at the front of the courtesy booth. The bag found in

front of the courtesy booth contained a second wig. One of the

bags was found to contain a sales receipt issued to Betty Nolan.

The receipt was traced and police interviewed Nolan. Nolan told

the police that petitioner Moore sometimes lived at her house,

sharing a room with her son Michael Pittman. Nolan told one of

the officers that Moore had been at Nolan's house on the day of

the offense. Moore and his sister both testified that Moore

moved out of Nolan's house several months before the offense

because he had an argument with Pittman. Moore and his sister

also testified that he could not have returned to the house

because Nolan changed the locks after the argument between Moore

and Pittman.

Police searched Nolan's home

and recovered a shotgun between the mattress and box springs of

Moore's bed. A ballistics expert testified at trial that it is

impossible to determine whether a particular shotgun was used in

an offense by examining the projectiles, or shot, from the

shotgun.Thus, the expert was unable to determine, from the size

8 shot recovered from the floor of the courtesy booth and from

McCarble's head, whether the shotgun recovered from Nolan's

house was the weapon used to kill McCarble. Several witnesses

testified, however, that the shotgun recovered from Nolan's home

was similar to or looked like the weapon that was aimed into the

courtesy booth during the robbery. The ballistics expert also

testified that one of the shells found with the shotgun

contained size 8 shot and that a single expended shell found

with the shotgun had indeed been fired from the shotgun

recovered from Nolan's house.

Police were unable to find

suitable fingerprints for comparison to Moore's on either the

shotgun or the plastic bags. Moore testified that Pittman owned

the shotgun, which had been stolen from one of Pittman's former

employers. The state did not offer any evidence relating to

whether the gun was registered or whom the gun was registered to.

Moore also testified that, according to Pradia, Pittman was the

third man who held the shotgun during the robbery. Moore

testified that Pittman had four prior robbery convictions.

Evidence offered at trial established that Pittman was then

incarcerated pursuant to a judgment of criminal conviction for

burglary of a building.

Police also discovered that

Nolan had several wigs and wig stands in her home. Photographs

were made of six wig stands. Of the six stands, only four had

wigs. Thus, two wigs, the number found at the crime scene, were

missing. The two wigs secured at the crime scene were tested for

hair samples. Although some small pieces of hair were obtained,

the samples were too small for any meaningful comparison to

exemplar hairs from Moore's head.

Meanwhile, police arrested

Koonce based upon the store customer's description of the

robbers' car and license plate number. Koonce gave a confession

implicating Pradia and Moore. Pradia's billfold was found in

Koonce's car. When Pradia heard police were looking for him, he

turned himself in. Pradia also gave a confession, and like

Koonce, Pradia implicated Moore in the robbery.

C. Moore's Arrest and

Interrogation

Based upon information

received from Koonce and Pradia and the evidence obtained from

Nolan's house, police obtained an arrest warrant for Moore.

Around the same time, police received a telephone call from

citizen Bobby White, who was an acquaintance of Moore's father,

Ernest "Junior" Moore. White told police that he had accompanied

Junior Moore and petitioner Bobby Moore to Moore's grandmother's

house in Coushatta, Louisiana on the morning of Tuesday, April

29, 1980, four days after the robbery and around the time of

Koonce's and Pradia's arrest. White told police that Moore took

luggage and that he remained in Coushatta when Junior Moore and

Bobby White returned to Houston on Wednesday, April 30, 1980.

Moore was still in Coushatta when Bobby White and Junior Moore

made a second trip to the grandmother's house on May 1 and 2.

When White returned to Houston from the second trip, on Friday,

May 2, 1980, he called the Houston police and told them that

Bobby Moore was in Coushatta at his grandmother's house.

Houston police contacted the

Louisiana State Police, who arrested Moore at his grandmother's

house. On May 5, 1980, Houston Police Officers D. W. Autrey and

Larry Ott, who had been investigating the robbery, traveled to

Louisiana to bring Moore back to Houston. Once the trio returned

to Houston, Moore was interrogated about his role in the crime.

The Director claims that this interrogation resulted in Moore's

confession, which was introduced at trial. Moore claims that,

although he was beaten to induce his cooperation, he never

signed a written statement. Moore introduced a booking photo of

himself taken three or four days after the interrogation that

reflects some swelling on the left side of his face and

head.Photos taken of a pretrial line-up done on May 7, 1980,

however, do not show any appreciable distortion in Moore's

features.

D. The Trial

Moore's case was called to

trial in July 1980. Moore was defended by Alfred J. Bonner, who

was retained and paid by Moore's family, and C. C. Devine. Early

in the trial, the state attempted to introduce Moore's

confession through Officer Ott. Moore's counsel objected and the

jury was removed from the courtroom while the trial court

considered whether Moore's confession would be admitted into

evidence.

Moore's purported confession

recites that Koonce, Pradia, and Moore were riding around in

Koonce's car looking for some place to rob. After casing the

store, the three men decided that Koonce would enter the

courtesy booth, that Pradia would remove money from the

registers, and that Moore was to guard the courtesy booth and

the front door with his shotgun. The confession recites that

Moore wore a wig and covered the shotgun with two plastic

shopping bags before entering the store. When Scott started

shouting that there was a robbery in progress, Moore shouted to

Koonce that it was time to leave. When Koonce did not respond,

Moore approached the front of the courtesy booth. About the

actual shooting, the confession states:

The old man in the booth

leaned over to open a drawer in the booth. I started trying to

push him back with the barrel of the shotgun. I was leaning over

the counter of the booth and I suddenly fell backwards and the

butt of the gun hit my arm and the gun went off. I didn't learn

until later that the man had been shot. I seen it on T.V. The

man must have been standing back up as I fell backwards and the

gun went off.

After the robbery, the

confession states that the three men ran out of the store and

drove to Betty Nolan's house. Moore stayed at Nolan's and Pradia

and Koonce left. The confession also states:

I swear I was

not trying to kill the old man and the whole thing was an

accident.

Officer Ott stated on voir

dire by the state that both the inculpatory portions of the

confession, demonstrating Moore's involvement, and the

exculpatory portions of the confession, tending to establish

that the shooting was an accident, were verbatim recitals of

Moore's voluntary statements concerning his participation in the

crime. Officer Ott testified that he typed Moore's confession,

which was executed on blue paper.

Moore testified on voir dire

that he had refused to sign any statement or confession. Moore

further testified that his refusal so angered the interrogating

officers that he was struck repeatedly on the left side of his

face. Moore conceded that he eventually signed two pieces of

blank white paper, but only because the officers told him he

would be released if he did so. Moore testified that he had not

signed anything printed on blue paper and that the signature on

the blue confession being offered by the state was not his own.

Moore's counsel argued that

the confession was inadmissible, either because it was not

signed by Moore or because it was involuntarily given. The trial

court denied Moore's motion to suppress and the confession was

deemed admissible. Before the jury was brought back in, however,

the state informed the trial court that it wished to exclude the

exculpatory portions of the confession quoted above, which

tended to establish that the shooting was accidental. Moore's

defense counsel stated that they had not reached a decision with

respect to whether they would be offering the remainder of the

confession. Moore's counsel secured a ruling from the trial

court prohibiting the state from making any reference to the

portions of the confession that were being omitted until that

decision could be made. In response, the state agreed to merely

cover the exculpatory language when entering the

inculpatoryportions of the confession, thus preserving the

language for later use by the defense. Once that agreement was

reached, however, Moore's counsel inexplicably changed course,

stating that they would not use the exculpatory portions of the

confession and that those portions should be completely "cut

out" of the exhibit given to the jury. As a result, the

exculpatory passages in the confession were "whited out," and

the confession presented to the jury contained no mention of the

actual shooting. Rather, the confession placed Moore at the

crime scene, holding a shotgun pointed in McCarble's direction,

and then, following a conspicuously large blank space where the

exculpatory text was deleted, the confession described how the

three men fled the store. Defense counsel's failure to offer the

exculpatory portions of Moore's confession, at either the guilt

phase or the punishment phase of Moore's trial, forms a

significant part of Moore's claim that he received ineffective

assistance of counsel.

In addition to the evidence

described above, the state also offered Pradia's testimony

against Moore in its case-in-chief. Pradia testified pursuant to

a plea bargain. Pradia testified that the three men met at Betty

Nolan's house on the morning of April 25, 1980, and then rode

around in Koonce's car deciding upon a store to rob. Pradia

testified that he cased the store before the robbery by going in

to see who was working and whether the robbery was feasible.

Pradia's testimony was corroborated by the testimony of store

employees who testified that they observed Pradia in the store

earlier in the day. Pradia's testimony was also consistent with

many details contained in the inculpatory portions of Moore's

confession which were submitted to the jury. Pradia told the

jury that when Koonce and Moore joined him in the car after the

robbery, Moore told Pradia that Moore shot someone inside the

store. Pradia testified that he did not believe Moore until he

saw the news coverage about McCarble's death.

Moore's counsel pursued an

alibi defense. Moore claims in this habeas action that his trial

counsel knew that Moore's confession was true; that is, that

Moore participated in the robbery and that he unintentionally

shot Jim McCarble. Moore maintains that counsel nonetheless

created a false alibi defense, and then pressured Moore and his

sisters Clara Jean Baker and Colleen McNiese to testify falsely

that Moore was in Coushatta, Louisiana at his grandmother's

house on April 25, 1980, the date of the offense. Clara Jean

Baker and petitioner Moore eventually testified before the jury

in support of the fabricated defense.

Without regard to whether

counsel knowingly suborned perjured testimony, as Moore alleges,

the presentation of the alibi defense can only be described as

pathetically weak. Moore's sister, Baker, initially testified

that she drove Moore to Coushatta, Louisiana on April 14, 1980

and picked him up the next Monday, April 21, 1980. The problem

with that testimony, of course, is that it did not place Moore

in Louisiana on the offense date, April 25, 1980. Baker then

changed her testimony to state that she drove Moore to Louisiana

on Monday, April 21, and did not pick him up until Monday, April

28, 1980. Baker testified that Moore went to Louisiana to care

for his grandmother because Moore's grandmother was ill. Baker

testified that she went to get him the next week because he was

bored. Notwithstanding Moore's boredom in Louisiana, Baker

testified that she was aware Moore returned to Louisiana the

following morning, Tuesday, April 29, 1980, with his father,

Junior Moore, and Bobby White.

Moore also testified in

support of the false alibi, telling the jury that he was in

Louisiana on the date of the alleged offense. But on cross-examination,

Moore testified that he was certain he went to Louisiana on

Monday, April 21, 1980, and that he stayed there only four or

five days. When confronted with the fact that he could have

therefore been back on April25, the day of the offense, Moore

backtracked and said he returned with his sister Baker on either

April 26 or April 27. Thus, Moore's own testimony conflicted

with that of Baker's with respect to when he returned to

Houston. That inconsistency was compounded by Moore's further

testimony that he returned to Louisiana with his father and

Bobby White on the same day he returned to Houston, rather than

the following day, as Baker had testified. Moore also repeated

in substance his voir dire testimony concerning the

circumstances of his arrest and interrogation, and his denial of

the written confession. Defense counsel attempted to bolster the

floundering alibi defense with the testimony of Houston Police

Officer J. H. Binford, who verified that neither Edna Scott nor

Debra Salazar nor Arthur Moreno was able to identify Moore in a

pretrial line-up as a person who participated in the robbery.

Not surprisingly, the state

responded to Moore's alibi defense on rebuttal with evidence

relating to extraneous conduct and offenses involving similar

conduct. See, e.g., Hughes v. State, 962 S.W.2d 89, 92 (Tex. App.--Houston

[1st Dist.] 1997, pet. ref'd) (subject to certain exceptions,

evidence of similar extraneous conduct may be admissible on the

issue of identity once a defendant raises an alibi defense). The

state first used its cross-examination of Moore to catalogue

Moore's prior convictions, three for burglary and one for

aggravated robbery. The state also called three witnesses to two

separate robberies of small grocery stores in the Houston area.

Those robberies occurred on April 11 and April 18, 1980, the two

Fridays preceding the Friday, April 25, 1980 robbery of the

Birdsall Super Market. Store employees positively identified

Moore as being one of the perpetrators at both robberies. As to

the first robbery, a store employee testified that Moore and two

other black men entered thestore, and that Moore stood at the

front of the courtesy booth holding a shotgun. As to the second

robbery, a store employee and a store customer testified that

Moore and another black man entered the store, and that Moore

held a shotgun during the robbery. This very damaging testimony

became admissible only because Moore pursued an alibi defense.

There is no dispute that the evidence would not have been

admissible had Moore pursued an accidental shooting defense

instead. The state also called a Louisiana State Police Officer

who knew Moore's grandmother very well and who arrested Moore at

his grandmother's house. That officer testified that, contrary

to Moore's testimony and that of his sister, Moore's grandmother

was and had been in good health. The officer also testified that

he had not seen Moore at the grandmother's house or in the

vicinity of the small town of Coushatta before the date of

arrest.

Closing arguments followed.

The state argued that Moore's confession was voluntary. The

state also argued that Moore's confession was accurate, at least

as to those portions submitted to the jury. Contrary to its pre-submission

agreement, the state referred to the obviously omitted portions

of the confession, stating that the confession was edited

because the state did not want to vouch for exculpatory language

Moore included in his confession. Notwithstanding that position,

the state argued that Officer Ott would not have included

exculpatory language in a fraudulently prepared confession. Thus,

the state relied upon the existence of the undisclosed and

excised exculpatory language to support its argument that the

confession was voluntary. The state did not, however, clarify

that the excluded language supported an accidental shooting

theory. To the contrary, the state tried to negate any such

impression by emphasizing that there had been no contention in

the case that the shooting was accidental.

Defense counsel Devine and

Bonner made separate arguments, which were in part contradictory.

For example, Devine criticized the police and their

investigationwhile Bonner said he had no complaint against the

police. Devine's argument was consistent with Moore's alibi

defense. But Bonner essentially abandoned the alibi defense,

stating that it made no difference whether Moore's sister

testified truthfully or whether Moore's grandmother was in fact

in ill health. Bonner characterized the evidence relating to

Moore's alibi as nothing more than a series of "rabbit trails."

Bonner placed his focus instead upon the alleged forgery of

Moore's confession, and upon whether the state's other evidence

was strong enough to place Moore at the Birdsall Super Market on

April 25, 1980.

The state's rebuttal argument

relied heavily upon the pitiful failure of the alibi defense.

The state also emphasized and made use of defense counsel's

apparent inability to agree, and their divergent positions in

closing argument to the jury.

During deliberations, the jury

sent out a note requesting that they be provided with "[b]oth

confessions of the Defendant." Notwithstanding that request and

the available argument that the state opened the door to

submission of Moore's unredacted confession by relying upon

redacted portions in its closing argument, the state and defense

counsel submitted, by agreement, only the redacted confession.

Three hours later, the jury returned a verdict of guilty.

The punishment phase of

Moore's trial began immediately. Under Texas law, Moore's jury

was required to return affirmative answers to each of two

special issues before the death penalty could be imposed. Those

issues were:

(1) whether the conduct of the

defendant that caused the death of the deceased was committed

deliberately and with reasonable expectation that the death of

the deceased or another would result; and

(2) whether there is a

probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of

violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society.

The state began by tendering

all of the state's guilt phase evidence into the punishment

phase record. The state then offered Moore's penitentiary

package, which contained the details of Moore's prior criminal

record. The state was permitted to explain the penitentiary

package to the jury, and the jury was again instructed that

Moore had three prior burglary convictions and one prior

aggravated robbery offense. Moore's counsel did not likewise

offer any explanatory argument to the jury on the penitentiary

package, notwithstanding that: (1) Moore was sentenced for each

of the four offenses on the same day; (2) Moore began serving

his sentence for each of the four convictions on the same day;

and (3) Moore was released from serving the balance of the four

concurrently imposed sentences after only two years, a factor

clearly relevant on the issue of future dangerousness. To the

contrary, Moore's counsel simply stipulated that the documents

comprising the penitentiary package were accurate. Besides

failing to respond to the state's evidence, defense counsel

offered no evidence on the issue of punishment. The evidentiary

portion of the punishment phase of Moore's capital punishment

trial concluded less than ten minutes after it had begun.

Counsel then made closing

arguments to the jury. Once again, defense counsel Devine and

Bonner made separate and somewhat contradictory arguments.

Devine argued that the shooting was accidental and unintentional.

Devine supported that position with argument relating to the

nature and the location of McCarble's wound, the small amount of

pressure required to discharge a firearm, and other

circumstances of the offense. Devine did not, however, support

that punishment phase argument with the best available evidence

that the shooting was indeed accidental -- Moore's unredacted

confession -- even though the record is clear that an unredacted

version of the confession was available and could have been

offered during the punishmentphase of Moore's trial. Devine also

argued that Moore would not present a continuing threat of

violence in the prison community. Devine failed, however, to

support that argument by focusing the jury upon evidence in the

penitentiary package that Moore was released early from his only

prior prison sentence.

Bonner encouraged the jury not

to make too much from defense counsel's apparent disagreement.

Bonner seemed to deride Devine's accidental shooting theory,

stating that Devine only argued the theory for the purpose of

ensuring that defense counsel were not lax in their duty.

Contrary to both Moore's confession and the jury's verdict,

Bonner then attempted to focus the jury on the defensive theory

that the state's evidence failed to show Moore was at the scene

of the crime. Neither Devine nor Bonner argued the alibi defense

that featured so prominently at the guilt phase of trial.

Together, Devine's and Bonner's arguments take up less than

fifteen pages of the punishment phase transcript.

The state closed by

highlighting defense counsel's failure to try and explain away

Moore's prior offenses, defense counsel's failure to call

character witnesses, and the brevity of defense counsel's

argument on the issue of punishment. The state relied upon

defense counsel's failure to offer these types of evidence as

support for the proposition that no such evidence existed. After

deliberation, the jury returned affirmative answers to the

special issues as required under Texas law for imposition of the

death penalty.

One week later, Moore was

sentenced to death. At sentencing, counsel Devine expressed the

desire to withdraw from his representation of Moore. Devine died

shortly thereafter. Bonner expressed the desire to continue

representing Moore on appeal, provided the trial court would

provide a record for that purpose.

E. Direct Appeal

Moore's case was automatically

appealed to the state's highest criminal court, the Texas Court

of Criminal Appeals. In the two and one-half year period between

December 1980 and June 1983, Bonner filed at least twelve

motions seeking an extension of the filing deadline for either

Moore's appellate brief or the statement of facts. During that

period, Bonner routinely missed filing deadlines, failing to

request an extension of time until he received notice that the

filing deadline had passed. Between January and April 1983,

Moore sent letters and pro se motions to the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals complaining that Bonner refused to communicate

with him and requesting permission to file a pro se brief on

appeal. Moore's pro se motions were denied. In May 1983, Bonner

requested a "final" extension of the brief filing deadline until

July 15, 1983. Bonner missed this deadline as well, and did not

file a brief on Moore's behalf until July 27, 1983, three years

after Moore's capital trial. The state filed a timely response

brief in August 1983.

Meanwhile, Moore continued to

send correspondence to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

objecting to Bonner's representation. In October 1983, the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals ordered the trial court to conduct a

hearing to determine whether Moore was making an informed

decision to proceed pro se on appeal. In December 1983, the

trial court conducted a hearing to determine whether Bonner

should continue as Moore's counsel. Moore rejected Bonner's

representation and requested that another lawyer be appointed.

Accordingly, attorney John Ward was appointed to replace Bonner

as Moore's counsel on appeal.

Between January 1984 and

September 1984, counsel Ward filed four additional motions for

an extension of the brief filing deadline. The Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals granted those motions. The final extension made

the brief due on October 3, 1984. Ward missed the October 3

filing deadline. In December 1984, the Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals issued a showcause order instructing Ward to file the

brief before January 7, 1985, or to show cause why he should not

be held in contempt of court. Ward eventually filed the brief on

the January 7, 1985 deadline. Ward's brief argued, inter alia,

that Moore's trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance

because they failed to investigate the availability of

mitigating background evidence and failed to present available

mitigating evidence at the punishment phase of Moore's capital

trial.

During the time

period for the state's response, Moore filed a pro se brief on

his own behalf. Moore's pro se brief argued, inter alia, that

trial counsel were ineffective for failing to call additional

alibi witnesses, such as his grandmother and his father.

In October 1985, more than

five years after Moore's capital trial, the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals issued an opinion affirming Moore's conviction

and death sentence. See Moore v. State, 700 S.W.2d 193 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1985). Noting the abundance of briefs on appeal, the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals purported to reach all of the

arguments presented in the various briefs filed by Bonner and

Ward, and by Moore acting pro se. While the Court made certain

rulings with respect to Ward's ineffective assistance of counsel

argument, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals expressly limited

those holdings by noting that the record on direct appeal is

generally inadequately developed to reflect trial counsel's

failings. See Moore, 700 S.W.2d at 204-05. Without precluding

the possibility that Moore's ineffective assistance of counsel

claims might be beneficially developed in further proceedings,

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals set forth rulings expressly

"limited to the record on appeal that is before us." Id. at 205.

Moore's execution date was thereafter set for February 26, 1986.

Moore's petition to the Supreme Court for writ of certiorari and

his application for stay of execution were denied on February

21, 1986. Moore v. Texas, 106 S. Ct. 1167 (1986).

F. Habeas Corpus Proceedings

On February 24, 1986, Moore,

represented by new counsel, filed an application for writ of

habeas corpus and a motion for stay of execution in state court.

The state trial court denied both Moore's application for habeas

corpus and Moore's motion for a stay of the February 26

execution date without a hearing. The Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals summarily affirmed that decision without opinion.

On February 25, 1986, Moore

filed a petition for habeas corpus relief and a motion for stay

of execution in federal district court. The district court

granted Moore a stay of execution. In June 1987, the district

court determined that Moore's federal habeas petition raised

certain factual and legal theories that had not been presented

to the state courts. Accordingly, the district court dismissed

Moore's first federal habeas petition, without prejudice to

refiling upon exhaustion.

In April 1992, Moore, now

represented by three new lawyers, filed his second application

for state habeas relief. Moore's April 1992 petition alleged,

inter alia, that Moore's trial counsel: (1) suborned perjury in

the presentation of Moore's alibi defense; (2) failed to conduct

an adequate pretrial investigation by interviewing Koonce and

Pradia and state witnesses to extraneous conduct; (3) excluded

exculpatory evidence that the shooting was accidental on the

basis of their erroneous belief that such evidence was per se

inconsistent with Moore's alibi defense; (4) unduly prejudiced

Moore by eliciting damaging testimony on essential elements of

the offense that was not otherwise introduced against Moore in

their cross-examination of Officer Autrey; and (5) failed to

investigate, develop, or present available mitigating evidence

that would have swayed the jury's decision on the special issues

in Moore's favor.

On April 23, 1993, the state

habeas court conducted an evidentiary hearing on Moore's various

ineffective assistance of counsel claims. The state habeas court

heard evidence from Bonner, Moore, Moore's sisters Clara Jean

Baker and Colleen McNiese, and other witnesses concerning trial

counsel's conduct. The state habeas court also heard substantial

evidence from an expert witness and Moore's family members

concerning Moore's tortured family background and his impaired

mental functioning. After the evidentiary hearing, the state

habeas court entered findings of fact and conclusions of law in

support of its determination that Moore did not receive

ineffective assistance of counsel at his 1980 trial. On October

4, 1993, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the state

habeas court's denial of habeas corpus relief.

On October 12, 1993, Moore

filed his second federal petition for federal habeas relief,

raising the same claims that were presented in the second state

habeas application. On October 21, 1993, the district court

denied Moore's request for an evidentiary hearing, reserving the

right to revisit the issue should a hearing become necessary. On

September 29, 1995, the district court entered an order holding

that Moore's trial counsel rendered deficient performance at

both the guilt and punishment phases of Moore's trial, and that

counsel's deficient performance prejudiced Moore at the

punishment phase of his trial. Accordingly, the district court

reversed the state court judgment against Moore as to punishment

only, and remanded to the state trial court for a new punishment

hearing. The Director appeals from that decision.

IV.

In making its determination

that Moore received ineffective assistance of counsel, the

district court adopted some, but considered and rejected other,

factual determinations made by the state habeas court. The

Director contends that the district court failed to afford these

state habeas court fact findings the deference required by the

pre-AEDPA version of 28 U.S.C. 2254(d).

The Director first argues that

a federal district court may not reject the factual

determinations made by a state habeas court without conducting

its own evidentiary hearing. We disagree. "Although the federal

district courts are vested with broad power on habeas to conduct

evidentiary hearings, we cannot say that it becomes the duty of

the court to exercise that power where, as here, the state trial

court has afforded the applicant[] a full and fair evidentiary

hearing." Heyd v. Brown, 406 F.2d 346, 347 (5th Cir. 1969); see

also West v. Johnson, 92 F.3d 1385, 1410 (5th Cir. 1996);

Lincecum v. Collins, 958 F.2d 1271, 1278-80 (5th Cir. 1992);

Winfrey v. Maggio, 664 F.2d 550 (5th Cir. Unit A Dec. 1981) (all

holding that the federal district court is not required to hold

an evidentiary hearing when the record is clearly adequate to

fairly dispose of the claims presented). We find no error

arising solely from the fact that the district court chose to

review the state habeas court's factual determinations without

conducting an evidentiary hearing on Moore's claims.

The Director also contends

that the district court impermissibly substituted its own view

of the facts for state habeas court findings entered after a

full and fair litigation of Moore's claims in the state habeas

court. Essentially, this amounts to a contention that the

district court failed to correctly apply the pre-AEDPA version

of 28 U.S.C. 2254(d). We will first define the deference

required by the pre-AEDPA version of 2254(d). Whether the

district court inappropriately rejected particularfindings will

be addressed in the context of the specific areas of deficient

performance identified by the district court.

The pre-AEDPA version of 28

U.S.C. 2254(d) obligates federal habeas courts to afford state

habeas court fact findings a presumption of correctness, subject

to an enumerated list of eight exceptions. See 28 U.S.C.

2254(d)(1)-(8) (1994). The first seven exceptions in essence

provide that the presumption of correctness does not apply

unless the petitioner's habeas claims have been fully and fairly

litigated in a state habeas court with jurisdiction to consider

the matter. We

have already determined, and the parties do not dispute, that

Moore's ineffective assistance of counsel claims received a full

and fair adjudication on the merits in the April 1993

evidentiary hearing conducted in the state habeas court. See

Moore, 101 F.3d at 1075. We therefore conclude that none of the

seven exceptions set forth as 2254(d)(1) through 2254(d)(7) are

applicable in this case to excuse the presumption of correctness

otherwise required by 2254(d).

Instead, the district court

expressly tied its selective rejection of the state habeas

court's factual determinations to 2254(d)(8), the final

exception in 2254. Section 2254(d)(8) provides that federal

habeas courts need not defer to state habeas court fact findings

that the federal habeas court determines are "not fairly

supported by the record." See 28 U.S.C. 2254(d)(8) (1994);

Bryant v. Scott, 28 F.3d 1411, 1417 (5th Cir. 1994). Under this

pre-AEDPA standard, a federal habeas court may not reject state

court factual determinations merely on the basis that it

disagrees with the state court's resolution. Marshall v.

Lonberger, 103 S. Ct. 843, 850 (1983); Loyd v. Smith, 899 F.2d

1416, 1425 (5th Cir. 1990). Indeed, the federal court may not

reject factual determinations unless it determines that they

lack even "fair support" in the record. Marshall, 103 S. Ct. at

850; Smith, 899 F.2d at 1425. But the deference embodied in the

pre-AEDPA version of 2254(d) does not require that the federal

court place blinders on its eyes before conducting a habeas

corpus review of a state record. To the contrary, the section

merely erects a starting place or presumption, that may be

examined in light of the state court record. See, e.g., Bryant,

28 F.3d at 1417-19. It is worth noting that the pre-AEDPA

standard is significantly less deferential to state habeas court

factual determinations in this regard than its AEDPA counterpart,

which prohibits the grant of relief unless the state court's

factual determination is plainly unreasonable in light of the

evidence submitted to the state habeas court. See 28 U.S.C.

2544(d)(2); Trevino v. Johnson, 168 F.3d 173, 181 (5th Cir.

1999), pet. for cert. filed, (U.S. June 17, 1999) (No. 98-9936).

In addition, 2254(d) does not

require a federal habeas court to defer to a state court's legal

conclusions. Once again, the pre-AEDPA standard permits, in this

regard, a far more liberal review of state habeas court findings

than is allowed by the stringent standard of review embodied in

AEDPA's version of 2254(d). Under AEDPA, a state court's legal

conclusion may not be disturbed absent a showing that the state

court conclusion iscontrary to, or involved an unreasonable

application of, clearly established law, as determined by the

United States Supreme Court. 28 U.S.C. 2254(d)(1). An

application of federal law is unreasonable only when "reasonable

jurists considering the question would be of one view that the

state court ruling was incorrect." Trevino, 168 F.3d at 181 (quoting

Drinkard, 97 F.3d at 769). Thus, AEDPA's standard of review both

restricts the federal habeas court's review of state factual

determinations, and interjects certain limitations upon the

federal habeas court's review of legal conclusions that were not

present under pre-AEDPA law.

When applying the pre-AEDPA

standard to ineffective assistance of counsel claims, this Court

has held that whether counsel was deficient, and whether the

deficiency, if any, prejudiced the petitioner within the meaning

of Strickland, are legal conclusions which both the district

court and this Court review de novo. See Bryant, 28 F.3d at 1414

("a state court's ultimate conclusion that counsel rendered

effective assistance is not a fact finding to which a federal

court must grant a presumption of correctness"); see also Carter

v. Johnson, 131 F.3d 452, 463 (5th Cir. 1997), cert. denied, 118

S. Ct. 1567 (1998); Motley v. Collins, 18 F.3d 1223, 1226 (5th

Cir. 1994); Black v. Collins, 962 F.2d 394, 401 (5th Cir. 1992);

Mattheson v. King, 751 F.2d 1432, 1439 (5th Cir. 1985). The

state court's subsidiary findings of specific historical facts

and state court credibility determinations are, however,

entitled to a presumption of correctness under 2254(d). Carter,

131 F.3d at 4643; Bryant, 28 F.3d at 1414 n.3. Thus, a state

habeas court's determination that counsel conducted a pretrial

investigation or that counsel's conduct was the result of a

fully informed strategic or tactical decision is a factual

determination, while the adequacy of the pretrial investigation

and the reasonableness of a particular strategic or tactical

decision is a question of law, entitled to de novo review. See

Horton v. Zant, 941 F.2d 1449, 1462 (11th Cir. 1992); see also

Bryant, 28 F.3d at 1414-19; Whitley, 977 F.2d at 158-59; Wilson,

813 F.2d at 672.

The Court is, therefore, not

required to condone unreasonable decisions parading under the

umbrella of strategy, or to fabricate tactical decisions on

behalf of counsel when it appears on the face of the record that

counsel made no strategic decision at all. Compare Mann v. Scott,

41 F.3d 968, 983-84 (5th Cir. 1994) (citing record evidence for

proposition that counsel made a strategic decision not to offer

mitigating evidence during the punishment phase of a capital

trial), with Whitley, 977 F.2d at 157-58 (concluding from the

record that counsel's failure to offer mitigating evidence

during the punishment phase of habeas petitioner's capital trial

was not the result of a considered strategic decision, and

therefore not entitled to deference), and Wilson, 813 F.2d at

672 (concluding that the existing record was inadequate for

purposes of determining whether counsel made a strategic

decision not to offer mitigating evidence during the punishment

phase of a capital trial or whether that decision

wasprofessionally reasonable); see also Whitley, 977 F.2d at 158

("The crucial distinction between strategic judgment calls and

plain omissions has echoed in the judgments of this court.");

Profitt v. Waldron, 831 F.2d 1245, 1248 (5th Cir. 1987) (Strickland's

measure of deference "must not be watered down into a disguised

form of acquiescence."); id. at 1249 (refusing to indulge

presumption of reasonableness as to "tactical" decision that

afforded no advantage to the defense). Rather, the fundamental

legal question is whether, viewed with the proper amount of

deference, counsel's performance was professionally reasonable

in light of all the circumstances. Strickland, 104 S. Ct. at

2066.

Having set forth the factual

background of this case and the appropriate standards governing

both Moore's substantive claimthat he received ineffective

assistance of counsel and the district court's treatment of

relevant findings by the state habeas court, we now proceed to

review the district court's application of those standards.

V.

A. Subornation of Perjury

and Selection of Alibi Defense

Moore claims that trial

counsel Bonner created a false alibi defense, and then suborned

perjury by pressuring Moore and his sisters Clara Jean Baker and

Colleen McNiese to testify in support of the alibi. Moore claims

that Bonner engaged in this conduct notwithstanding Bonner's

knowledge that Moore's confession accurately portrayed the

shooting as accidental, rather than intentional. Moore

identifies this conduct as deficient performance within the

meaning of Strickland.

Moore supported his habeas

claim in the state habeas evidentiary hearing with his own

testimony, and that of his sisters, to the effect that Bonner

told them on the day of trial that alibi was the only possible

means of avoiding the death penalty. McNiese testified that she

did not understand what Bonner was asking her to do. Baker

testified that she understood, and that she testified falsely at

Moore's criminal trial shortly after talking to Bonner because

she thought she was saving her brother's life.

The state habeas court heard

conflicting evidence from Bonner that the alibi defense was

insisted upon by Moore and corroborated by his family. Bonner

also testified that he was skeptical of the alibi defense at

first because most of his clients initially protested innocence,

but that he became increasingly more comfortable with using the

defense when he determined in the course of his pretrial

investigation that none of the state's witnesses had been able

to identify Moore, that Moore no longer lived with Betty Nolan,

that Nolan's son, Michael Pittman, had a record, that the

shotgun recovered from Nolan's house could not be definitively

linked to either Moore or the offense, and that the state was

not able to connect either of the wigs found at the crime scene

to Moore using exemplar hair samples.

The state habeas court

resolved this conflicting evidence with a credibility

determination. The state court found that Bonner's testimony on

the issue of subornation was credible, and that Bonner did not

suborn perjury or attempt to suborn perjury from Moore's sisters.

Implicit in that fact finding is the additional determination

that Bonner likewise did not suborn perjury from Moore.

The district court found

deficient performance based upon counsel's presentation of a

perjured alibi defense. The district court identified the state

habeas court's factual determination that Bonner did not suborn

perjury, but stated that the fact finding was not entitled

deference because the state habeas court's finding was "confounded

by overwhelming evidence to the contrary and is not supported by

the record." The district court also found that the "conduct of

trial counsel was so contrary to the great weight of evidence

that only a foolish man would insist upon presenting such a

defense." Both rationales for rejecting the state habeas court's

factual determination are problematic.

With regard to the first

rationale, we note that the state court's factual finding that

Bonner did not suborn or attempt to suborn perjury is a

credibility determination made on the basis of conflicting

evidence that is virtually unreviewable by the district court or

our Court. Marshall, 103 S. Ct. at 850. Section 2254(d) does not

grant federal habeas courts a "license to redetermine [the]

credibility of witnesses whose demeanor has been observed by the

state trial court." Id. at 851. Moreover, even though we may

share the district court's skepticism, the state habeas court's

credibility determination draws fair support from the record in

the form of Moore's trial testimony and Bonner's

evidentiaryhearing testimony. For that reason, the district

court's first rationale for rejecting the state habeas court's

credibility determination and its contrary fact finding must be

rejected as clearly erroneous. See Bryant, 28 F.3d at 1414 n.3.

The district court's second

rationale is more subtle, but is apparently driven by the

underlying premise that a reasonably competent attorney would

have dissuaded Moore from pursuing an alibi defense. The

district court opined that trial counsel cannot be permitted to

evade their burden to provide reasonably effective assistance

under the constitution by shifting the blame for selection of an

implausible defense to the defendant.

Although we find ourselves

somewhat in sympathy with the district court's comments, we

cannot agree. Moore is presumed to be the master of his own

defense. See Faretta v. California, 95 S. Ct. 2525, 2533-34

(1975); United States v. Masat, 896 F.2d 88, 92 (5th Cir. 1990);

Mulligan v. Kemp, 771 F.2d 1436, 1441-42 (11th Cir. 1985). Were

it otherwise, we might well face ineffective assistance of

counsel challenges anytime a chosen defense failed. Moreover,

Moore bears the burden of proving his allegation that the alibi

defense was unwillingly foisted upon him. See Brewer v. Aiken,

935 F.2d 850, 860 (7th Cir. 1991) ("[W]e refuse to hold that the

presentation of perjured testimony at the request of the

defendant is adequate to constitute ineffective assistance of

counsel."). The state habeas court found that Moore maintained

his innocence and endorsed the alibi defense at trial. That

determination is fairly supported by Moore's trial testimony and

Bonner's evidentiary hearing testimony. In addition to the

evidence described above, the state tendered excerpts from

Moore's pro se brief on direct appeal into the record of the

state court habeas proceeding. Moore's pro se brief argues at

length that trial counsel were ineffective for failing to call

additional witnesses, including his grandmother and father, who

would have testified in support of his alibi defense. When asked

about this argument during the evidentiary hearing in the state

habeas court, Moore conceded that he thought the argument should

be raised. There is every indication, as the state habeas court

found, that Moore maintained his innocence and insisted upon an

alibi defense, both during his trial and on direct appeal.

Neither can we accept Moore's

contention that counsel's decision to pursue an alibi defense

was unreasonable as a matter of law, without regard to who

selected the defense, because it was at odds with the known

facts. We have already held that Moore chose the alibi defense.

Counsel will rarely be ineffective for merely failing to

successfully persuade an insistent defendant to abandon an

unlikely defense. See Mulligan, 771 F.2d at 1442. Moreover, we

cannot say that the alibi defense was necessarily at odds with

the evidence known to counsel at the time Moore's trial began.

None of the state's witnesses had been able to identify Moore.

In addition, Moore's physical appearance did not match eye-witness

accounts of a taller man from Edna Scott. Neither the gun nor

the wigs nor the plastic bags could be tied to Moore by way of

fingerprints or exemplar hairs. The gun itself could not be

definitively tied to the offense. Moreover, Michael Pittman had

a significant prior record and was arguably as likely a suspect

as Moore.

Moore counters that the alibi

defense became untenable and should have been abandoned once his

confession was ruled admissible. The district court agreed. We

agree that succeeding on an alibi defense, particularly in the

face of a defendant's admissible confession is "similar to one

trying to climb by himself the tallest mountain in the world."

Moore, 700 S.W.2d at 205. But there is no obvious conflict in

the record evidence. Moore testified at trial before the jury

that he did not sign the confession. Moore testified at trial

before the jury in support of the alibi defense. Moore, acting

pro se, pursuedthe alibi defense on direct appeal. Whatever

inherent inconsistency was created by the admission of Moore's

confession was cured by his testimony that the confession was

invalid and his contemporaneous testimony that he was somewhere

else when the crime was committed.

For the foregoing reasons, we

decline to find deficient performance on the basis of Moore's

allegation that counsel suborned or attempted to suborn perjury

in their presentation of the false alibi defense or that counsel

should have persuaded Moore to abandon the alibi defense.

B. Inadequate Pretrial

Investigation

Moore also maintains that

counsel's decision to pursue an alibi defense was unreasonable

because counsel failed to conduct an adequate pretrial

investigation into the controlling law and facts.

Moore contends that counsel's

factual investigation of Moore's alibi defense was insufficient.

This argument is divided into two separate components. First,

Moore maintains that counsel should have determined that the

support for Moore's alibi, that he was with his grandmother in

Louisiana, was weak. Second, Moore argues that counsel were

ineffective for failing to contact or interview or otherwise

discern the testimony of state's witnesses to extraneous conduct

committed by Moore.

With regard to the first

argument, the state habeas court concluded that counsel

conducted a reasonable and independent pretrial investigation.

This conclusion of law rested upon factual determinations that

counsel discussed the alibi defense with Moore and with Moore's

family members, and that Moore's family supported the defense.

The district court accepted the premise that counsel met with

Moore and his family, but rejected the conclusion of law that

counsel's pretrial investigation was therefore independent or

reasonable. We review that determination of law de novo.

Moore's argument that counsel

failed to conduct a sufficient investigation into the facts

underlying his alibi defense is unavailing. As an initial matter,

Moore's ability to meet his burden on this point is

substantially weakened by our conclusion that Moore himself

chose and insisted upon the alibi defense. Moore is essentially

arguing that counsel should have expended pretrial resources

unearthing evidence to contradict their client's chosen defense.

We are persuaded that the record adequately supports the

proposition that there was sufficient investigation, at least as

to the veracity of Moore's alibi that he was in Louisiana when

the offense occurred. Moore selected the defense. Bonner

interviewed Moore and Moore's family members. Bonner traveled to

Louisiana to interview Moore's grandmother. In addition, Bonner

reviewed the state's files, ascertaining that the physical

evidence, and the testimonial evidence to be offered in the

state's case-in-chief were consistent with Moore's alibi. To the

extent that the confession was inconsistent with the alibi

defense, Moore's trial testimony that the confession was invalid

cured any problem. We therefore decline to find deficient

performance on the theory that counsel failed to adequately

develop facts contradicting the alibi defense.

Moore's second argument is

that counsel were ineffective for failing to ascertain what

evidence of similar extraneous conduct the state might offer in

rebuttal to his alibi defense. In contrast to its case-in-chief,

the state introduced substantial and highly probative evidence

that Moore, carrying a shotgun, robbed two small grocery stores

on the two Fridays preceding the Friday, April 25, 1980, robbery

of the Birdsall Super Market. All of the state's three rebuttal

witnesses were able to positively identify Moore. There can be

no doubt that this evidence was critical to Moore's conviction.

Prior to the state's case on rebuttal, none of the state's

witnesses had been able to unconditionallyplace Moore at the

scene of the crime. Moreover, it is undisputed that this

damaging evidence was admissible only because Moore chose the

alibi defense.

Moore argues that counsel

acted unreasonably because they simply did not understand that

Texas law would permit the state to rebut Moore's alibi with

evidence of similar extraneous conduct. The state habeas court

did not make any explicit findings of fact with regard to this

issue. The state habeas court did find, however, that counsel

made reasonable attempts to investigate potentially admissible

extraneous conduct. Thus, the state habeas court implicitly

found that counsel were aware of the controlling principles of

Texas law that made extraneous conduct admissible to rebut a

defendant's alibi defense. That finding is consistent with

Bonner's state habeas hearing testimony that he knew extraneous

conduct might come in and that he informed Moore of that

possibility. The district court did not expressly address this

implicit finding, but did conclude that counsel were unprepared

to meet extraneous offenses that came in as a result of alibi.

Moore supports this argument

with citations to counsel's trial objections. In those

objections, counsel maintained that the extraneous conduct was

inadmissible because not sufficiently proven. Counsel reasserted

those arguments, with considerable persuasive force, on direct

appeal. Moore, 700 S.W.2d at 198-201. Indeed, the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals wrote at length about both the general rule

that extraneous conduct may be admissible to rebut an alibi

defense and the exceptions to that general rule, as applied to

Moore's case. Id. Viewed in the context of the entire trial

record and the controlling principles of Texas law, we cannot

say that counsel's trial objections demonstrate that counsel was

not aware that extraneous conduct might be offered on rebuttal.

We therefore conclude that the state habeas court's fact finding

that Bonner was aware of the applicable principles of law is

fairly supported by the record, and therefore entitled to

deference from this Court.

Moore next argues that counsel

had an affirmative duty to identify the state's witnesses to

extraneous conduct and to interview those witnesses if possible.

See Bryant, 28 F.3d at 1415 (finding ineffective assistance of

counsel based upon counsel's failure to interview potential

witnesses); see also Gray v. Lucas, 677 F.2d 1086, 1093 n.5 (5th

Cir. 1982) (noting that an ineffective assistance of counsel

claim may be based upon counsel's failure to interview critical

witnesses). Bonner conceded in the state habeas hearing that the

state's file included a list of witnesses slated to testify that

Moore had participated in similar extraneous offenses.

Notwithstanding that knowledge, Bonner admitted that he made no

attempt to contact those witnesses or to ascertain the content

of their potential testimony. See Bryant, 28 F.3d at 1417 (counsel's

failure to contact potential witnesses was uninformed by any

investigation and was therefore not a strategic choice entitled

to deference under Strickland).

Bonner testified that he did

not know whether Devine had contacted the extraneous witnesses.

The state habeas court found, on the force of Bonner's testimony,

that Devine interviewed the extraneous witnesses. The district

court did not address this factual determination, aside from

noting that counsel's pretrial investigation into extraneous

conduct was inadequate in light of the chosen alibi defense.

We agree. Bonner's testimony

is not probative with respect to whether Devine contacted the

extraneous witnesses. Bonner said he did not know. He later

qualified that testimony by stating that Devine might have

handled that part of the case, but that assertion is

contradicted by the fact that Bonner conducted the cross-examination

of one of the state's star rebuttal witnesses. Moreover,

counsel's trial objections and their pathetically weak cross-examinations

of the state's rebuttal witnesses undermine beyond any

reasonable doubt the proposition that counselfollowed up on

information in the state's file by attempting to interview the

state's witnesses to extraneous conduct or by independently

investigating the damaging allegation that Moore was involved in

two very similar robberies on the two Fridays preceding the

Birdsall Super Market robbery. In counsel's own words: "We

haven't had a chance to prepare a defense about things that have

occurred at other places. We don't even know what is going on

here." For the foregoing reasons, the state habeas court's fact

finding that Devine contacted the state's witnesses to

extraneous conduct is not fairly supported by the record, and is

therefore not entitled to deference under 2254(d).

Moreover, and without regard

to whether Devine actually contacted the state's witnesses to

extraneous conduct, the record quite plainly establishes that

counsel failed to include any consideration of the state's

evidence of extraneous conduct when counseling Moore about the

alibi defense. Thus, even if the investigation was adequate,

counsel's response to the admissible evidence was so

unreasonable as to fall well outside the bounds of reasonable

professional performance. For the foregoing reasons, we find

deficient performance on the basis that counsel failed to

investigate the substance of evidence to be introduced on

rebuttal in response to Moore's alibi defense, or proceeded

unreasonably in light of that evidence.

C. Exclusion

of Exculpatory Language in Moore's Confession

Moore contends that his

counsel provided constitutionally deficient performance in their

handling of his confession during the guilt phase of trial.

Moore's confession contained the following exculpatory language:

The old man in the booth

leaned over to open a drawer in the booth. I started trying to

push him back with the barrel of the shotgun. I was leaning over

the counter of the booth and I suddenly fell backwards and the

butt of the gun hit my arm and the gun went off. I didn't learn