Fletcher Thomas Mann,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

Wayne Scott, Director Texas Department of

Criminal Justice,

Institutional Division, Respondent-Appellee.

No. 93-9006

Federal

Circuits, 5th Cir.

December 21,

1994

Appeal from

the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas.

Before KING, HIGGINBOTHAM,

and JONES, Circuit Judges.

KING, Circuit Judge:

Fletcher Thomas Mann, a Texas

death row inmate convicted of capital murder,

appeals the district court's denial of his

petition for a writ of habeas corpus. For the

reasons set forth below, we affirm.

I. PROCEDURAL POSTURE

Mann was convicted of the

1981 murder of Christopher Lee Bates and

sentenced to death by a Texas jury. Mann's

conviction was affirmed by the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals on October 22, 1986. Mann v.

State, 718 S.W.2d 741 (Tex.Crim.App.1986). The

United States Supreme Court denied certiorari on

April 6, 1987. Mann v. Texas,

481 U.S. 1007 , 107 S.Ct. 1633, 95 L.Ed.2d

206 (1987).

Mann began a collateral

attack on his conviction by filing his first

petition for a writ of habeas corpus and stay of

execution in the Criminal District Court of

Dallas County, Texas; the judge recommended that

Mann's petition be denied on the merits. On June

23, 1987, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

accepted the state trial court's recommendation

and denied Mann's petition in an unpublished

opinion.

The same day, Mann filed a

petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the

United States District Court for the Northern

District of Texas. The district court granted a

temporary stay of execution, but ultimately

found Mann's petition to be meritless. Mann v.

Lynaugh, 688 F.Supp. 1121 (N.D.Tex.1987). Mann

next filed notice of appeal to this court, which

dismissed the appeal because it was not timely

filed. Mann v. Lynaugh, 840 F.2d 1194 (5th

Cir.1988).

On June 17, 1988, Mann filed

a motion for relief from judgment pursuant to

Rule 60(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, claiming that his trial counsel's

negligent failure to file a timely appeal should

not deny him his right to appellate review.

While Mann's 60(b) motion was pending in federal

district court, Mann simultaneously filed

another petition for a writ of habeas corpus

with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

The federal district court

granted Mann's 60(b) motion, staying his

execution; it also retained jurisdiction over

the case and directed Mann to exhaust state

court remedies on certain new claims. Mann v.

Lynaugh, 690 F.Supp. 562 (N.D.Tex.1988). The

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed Mann's

petition without prejudice on grounds that Mann

was required by state law to first seek relief

from the state trial court. Mann filed his

petition with the state trial court on July 12,

1988; however, the state trial court abstained

on grounds of comity because the federal

district court still retained jurisdiction.

On November 10, 1988, the

federal district court lifted its stay of Mann's

execution, thereby relinquishing its

jurisdiction over the case and freeing the state

courts to proceed. Mann then refiled his habeas

petition in state court. On January 10, 1989, in

an unpublished opinion, the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals denied relief on the

recommendation of the state trial court. Since

there was no longer any stay order in effect,

Mann's execution was scheduled for December 5,

1990.

Mann next sought and received

a stay of execution and leave to reinstate his

federal habeas petition in the federal district

court.

The federal magistrate to whom Mann's case was

assigned recommended that relief be denied. On

September 7, 1993, following a de novo review,

the federal district court concurred with the

magistrate and entered final judgment denying

relief. Mann then filed a timely notice of

appeal. Shortly thereafter, the district court

issued a certificate of probable cause. For the

reasons set forth below, we affirm.

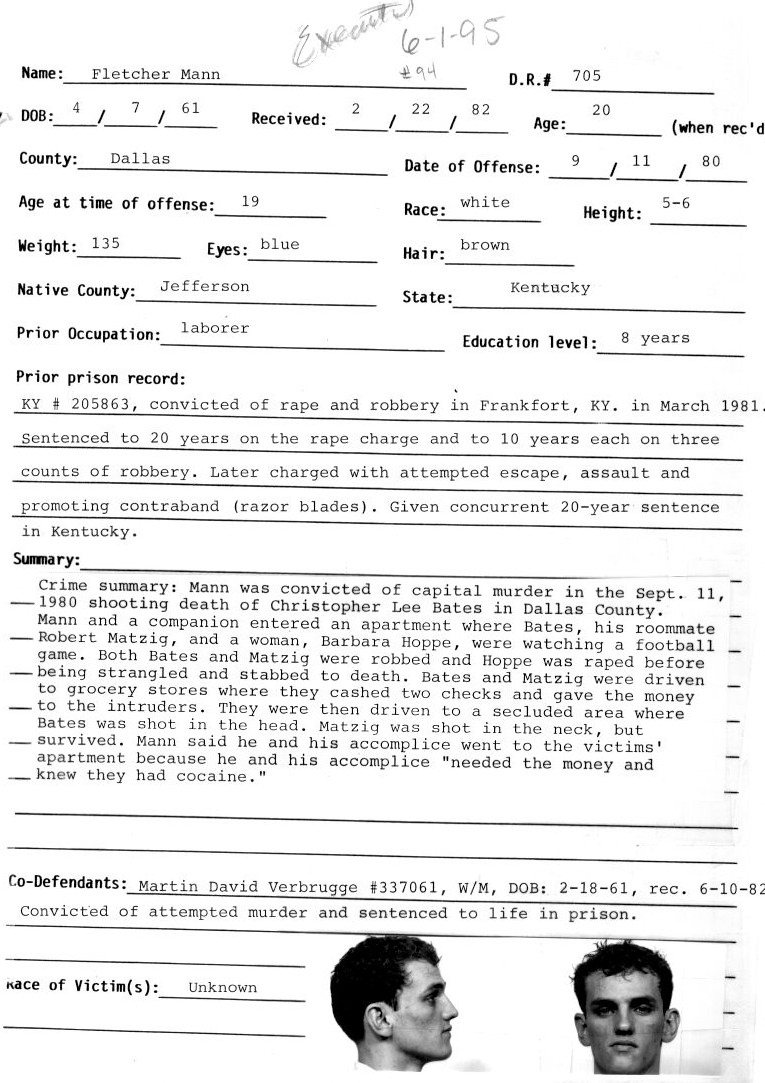

II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

In the early evening hours of

September 11, 1980, Mann and Martin David

Verbrugge knocked on the door of a Dallas

apartment shared by Christopher Bates and Robert

Matzig, who were watching a football game with

their friend Barbara Hoppe. When Matzig answered

the door, Mann and Verbrugge brandished pistols

and forced their way inside. Bates and Matzig

were instructed to lie on their stomachs on the

living room floor and were bound at the arms and

legs. Mann and Verbrugge went through their

pockets and took their money. Hoppe was taken

into the bedroom, where she was beaten, raped

and stabbed to death.

Mann exited the bedroom and

pointed a gun at the back of Matzig's head.

Matzig pleaded for his life, offering to write

Mann a check for the full amount in his account.

Mann and Verbrugge agreed and ordered Matzig to

write several smaller checks and cash them at

local grocery stores.

Over the next several hours,

the four men drove around Dallas in Matzig's car,

attempting to cash Matzig's checks. Bates and

Matzig were held under gunpoint the entire time.

Due to the late hour, Matzig was able to cash

only about $75.00 worth of checks. Matzig wrote

a final check in the amount of $1,000 which was

to be cashed by Mann or Verbrugge the following

morning.

Mann directed Matzig to drive

to a secluded area. When Mann and Verbrugge

alighted from the car, Matzig attempted to drive

away, but the car stalled. Mann and Verbrugge

forced Matzig and Bates from the vehicle, took

them into the woods, and ordered them to lie on

their stomachs. Matzig saw Mann standing over

Bates' head, preparing to shoot. Matzig tried to

run away, but he tripped and fell.

Bates was shot in the back of

the head with a .38 revolver. Matzig was shot in

the neck with a .38 revolver and was severely

wounded, but still alive. Matzig heard the

gunshots, but he did not see who pulled the

trigger. Mann and Verbrugge fled the scene in

Matzig's car. Meanwhile, Matzig crawled to a

nearby bulk mail center and was rescued. Fearing

that Matzig was not dead, Mann and Verbrugge

returned to the scene to finish the job; however,

the authorities had already arrived on the scene,

and the two fled once again.

Mann was charged with

murdering Bates in the course of robbing Matzig,

a capital crime under Texas law. TEX.PENAL CODE

ANN. Sec. 19.03(a)(2) (West 1994).

Pursuant to article 37.071 of the Texas Code of

Criminal Procedure, the jury answered each of

three special issues

in the affirmative, and Mann was sentenced to

death by lethal injection.

III. STANDARD OF REVIEW

In considering a federal

habeas corpus petition presented by a prisoner

in state custody, federal courts must generally

accord a presumption of correctness to any state

court factual findings. See 28 U.S.C. Sec .

2254(d). We review the district court's findings

of fact for clear error, but decide any issues

of law de novo. Barnard v. Collins, 958 F.2d

634, 636 (5th Cir.1992), cert. denied, --- U.S.

----, 113 S.Ct. 990, 122 L.Ed.2d 142 (1993);

Humphrey v. Lynaugh, 861 F.2d 875, 876 (5th

Cir.1988), cert. denied,

490 U.S. 1024 , 109 S.Ct. 1755, 104 L.Ed.2d

191 (1989).

IV. ANALYSIS

Mann posits eight arguments

in his petition to this court: (1) his

confession was obtained in violation of his

Sixth Amendment right to counsel; (2) the trial

court's failure to instruct the jury on the

lesser included offense of murder violated his

Fourteenth Amendment right to due process; (3)

the Texas sentencing statute unconstitutionally

prevented him from introducing mitigating

evidence at trial; (4) the trial court

unconstitutionally excluded certain venire

members for cause; (5) the prosecutor's closing

comments regarding the word "deliberate" in the

Texas capital sentencing statute violated state

law and rendered his conviction constitutionally

defective; (6) his trial counsel was

constitutionally ineffective; (7) the

prosecutor's closing argument unconstitutionally

misled jurors into believing that they were not

responsible for imposing the death sentence; and

(8) the federal district court erred by refusing

to hold an evidentiary hearing regarding certain

mitigating evidence. We proceed to analyze each

of these claims.

A. Sixth Amendment Right

to Counsel.

Mann argues that the state

trial court erred in allowing his confession to

be placed before the jury because it was

obtained in violation of his Sixth Amendment

right to counsel. Specifically, Mann contends

that the police knowingly circumvented his right

to have counsel present during his interrogation

in violation of Maine v. Moulton, 474 U.S. 159,

106 S.Ct. 477, 88 L.Ed.2d 481 (1985).

1. Factual Background.

A brief recitation of the

events leading up to Mann's confession is

required in order to fully evaluate his claim.

In June 1981, the Dallas police learned that

Mann was being held in custody in Bulitt County,

Kentucky, on an unrelated rape charge. Detective

Gholston of the Dallas Police Department

travelled to Kentucky to serve arrest warrants

on Mann and to attempt to interview him.

Upon his arrival in Kentucky,

Detective Gholston read Mann his Miranda rights

and informed Mann that he wanted to speak with

him following his arraignment on the Texas

charges. The Kentucky court appointed a local

attorney, Sean Delahanty, to represent Mann at

the arraignment. Following the arraignment and

consultation with Mann, Delahanty informed

Gholston that Mann was willing to talk, but only

if Delahanty were present and asked the

questions. Gholston rejected these terms.

Delahanty remained at the jail until the close

of visiting hours, hoping to ward off an

interrogation of Mann.

Later that afternoon, officer

Ronnie Popplewell of the Bulitt County Sheriff's

Department told Gholston that he intended to

transport Mann to a hospital in Louisville (approximately

25 miles away) in order to obtain a blood sample

for use in the Kentucky rape charge. Gholston,

who had lost his luggage on the flight from

Dallas to Louisville, asked Popplewell if he

could ride along and stop at the airport to

check on his luggage. Popplewell agreed, and the

trio set off for Louisville with Popplewell

behind the wheel, and Gholston and Mann in the

back seat.

There is conflicting trial

testimony as to precisely what conversation took

place during the trip to Louisville. Gholston

and Popplewell testified that Mann initiated

conversation regarding the Texas charge and that

he was curious to know what information the

police had regarding that crime. Conversely,

Mann testified that he told Gholston that he did

not want to talk and that he wanted a lawyer,

but was told that he did not need one.

Once the trio returned to the

police station in Bulitt County, several facts

are undisputed: (1) Gholston called the Dallas

Police Department and asked them not to question

Mann's mother; (2) Gholston asked Mann if he

would like to make a statement, to which Mann

responded affirmatively; (3) Gholston read Mann

his Miranda rights and asked Mann if he

understood them, including his right to counsel;

(4) Mann stated that he understood each of his

Miranda rights; (5) Mann made an oral confession

which was simultaneously transcribed in longhand

by Popplewell; (6) Popplewell typed the

confession and presented it to Mann; (7) the

typed confession was read out loud to Mann to

ensure its accuracy; (8) the top of each page of

the typed confession contained a recitation of

the Miranda warnings and a statement that those

rights were being knowingly, intelligently, and

voluntarily waived;

(9) Mann read the confession and signed each of

the four pages.

2. Standard of Review.

Whether a constitutional

right has been waived--including the Sixth

Amendment right to counsel--is a question of

federal law over which we have plenary review

power. Brewer v. Williams, 430 U.S. 387, 397 n.

4, 97 S.Ct. 1232, 1239 n. 4, 51 L.Ed.2d 424

(1977); Self v. Collins, 973 F.2d 1198, 1204

(5th Cir.1992), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 113

S.Ct. 1613, 123 L.Ed.2d 173 (1993). However, in

the interest of comity, federal courts must

presume the correctness of underlying state

court factual determinations absent proof of

some defect in the factfinding process. 28 U.S.C.

Sec . 2254(d); Sumner v. Mata, 449 U.S.

539, 547, 101 S.Ct. 764, 769, 66 L.Ed.2d 722

(1981).

We do not lightly find a

waiver of a constitutional right. Courts must "indulge

in every reasonable presumption against waiver,"

Brewer, 430 U.S. at 404, 97 S.Ct. at 1242; thus,

the state bears the burden of proving that an "intentional

relinquishment or abandonment" of the right has

occurred. Id. (quoting Johnson v. Zerbst, 304

U.S. 458, 464, 58 S.Ct. 1019, 1023, 82 L.Ed.

1461 (1938)).

Whether a voluntary, knowing,

and intelligent waiver of constitutional rights

has occurred is determined according to the

totality of the circumstances, including the

background, experience, and conduct of the

accused. Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 482,

101 S.Ct. 1880, 1883-84, 68 L.Ed.2d 378 (1981).

Thus, in the case at hand,

the state bears the burden of proving that Mann

knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily waived

his Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

5] We must therefore look to the totality of the

circumstances to determine if a valid waiver

occurred.

3. Analysis.

The state argues that Edwards

v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 101 S.Ct. 1880, 68

L.Ed.2d 378 (1981), provides the contours of

analysis regarding waiver of the Sixth Amendment

right to counsel. In Edwards, the Supreme Court

held that interrogation of the accused must

cease upon invocation of his Fifth Amendment--not

Sixth Amendment--right to counsel, unless the

accused "initiates further communication,

exchanges, or conversations with the police." Id.

at 485, 101 S.Ct. at 1885.

In Michigan v. Jackson, 475

U.S. 625, 106 S.Ct. 1404, 89 L.Ed.2d 631 (1986),

the Court extended the Edwards prophylactic "no

further interrogation" rule to the Sixth

Amendment context. The Court held that "if

police initiate interrogation after a

defendant's assertion, at an arraignment or

similar proceeding, of his right to counsel, any

waiver of the defendant's right to counsel for

that police-initiated interrogation is invalid."

Id. at 636, 106 S.Ct. at 1411.

We assume in this case that

Mann had asserted his right to counsel prior to

the time his confession was obtained, and the

parties do not contend otherwise. Thus, the rule

of Jackson prohibited "police-initiated

interrogation" of Mann. At the close of the

suppression hearing that preceded Mann's trial,

the state trial court made these oral findings:

THE COURT: All right. First

off, the Court will observe that all of the

testimony establishes that the confession was

freely and voluntarily given. Further, it will

be the ruling of the Court that the giving of

the confession was not tainted in any way by any

conduct of any law enforcement officer.

Further, the Court will find

specifically that, under the believable

testimony, that [sic] the confession was

obtained from the defendant at a time in which

he was voluntarily willing to talk and was not

requesting an attorney or objecting to being

interrogated.

. . . .

* * *

I'm going to allow the

statement to be admitted for the jury's

consideration.

The district court concluded

that in making these findings, the state trial

judge necessarily found that Mann initiated the

conversations with Gholston during the trip to

Louisville. Although it is difficult to reach

that conclusion when examining only the findings

themselves, when we look at those findings in

the context of the argument made by Mann's

counsel, we agree.

Mann's counsel argued to the

state trial judge that the Supreme Court cases

of Edwards, Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291,

100 S.Ct. 1682, 64 L.Ed.2d 297 (1980), and

Brewer v. Williams, 430 U.S. 387, 97 S.Ct. 1232,

51 L.Ed.2d 424 (1977), imposed an initiation

requirement in the Sixth Amendment context

whereby the state was required "to desist

approaching [Mann] any further," once Mann's

Sixth Amendment right to counsel had attached.

Mann's counsel contended that by approaching

Mann outside the presence of counsel the police

"were specifically going against the tenets of

those cases."

Against the backdrop of that

argument, and faced with a conflict in the

testimony about who initiated the conversation

which led to Mann's confession, the district

court believed that the state trial court had

credited the testimony of the police officers

and implicitly found that Mann had initiated the

conversation.

See Marshall v. Lonberger, 459 U.S. 422, 103

S.Ct. 843, 74 L.Ed.2d 646 (1983) (court is

presumed to have implicitly found facts

necessary to support its conclusions).

The district court also noted

that the state trial court explicitly found that

Mann waived his right to consult with his

attorney or to have him present when the

confession was given. Again, in the context of

the testimony and the argument of Mann's counsel,

we agree. These factual findings are entitled to

a presumption of correctness pursuant to 28

U.S.C. Sec . 2254(d), and Mann has

offered no evidence to overcome this presumption.

Thus, Mann's Sixth Amendment claim must fail.

Mann's counsel argues that

the key issue regarding waiver in this case is

not whether Mann "initiated" any conversation

with police, but whether the state notified

Mann's counsel prior to engaging in

interrogation and obtaining the confession, as

Mann's counsel testified he had requested. As

authority for that proposition, Mann cites Maine

v. Moulton, 474 U.S. 159, 106 S.Ct. 477, 88 L.Ed.2d

481 (1985), which condemns "knowing[ ]

circumventi[on] [of] the accused's right to have

counsel present in a confrontation between the

accused and a state agent." Id. at 176, 106 S.Ct.

at 487.

Neither Maine nor any other

case that predates the denial of Mann's petition

for certiorari stands for the proposition that

the Sixth Amendment is violated when the police

accept a defendant's invitation to engage in

conversation about the crime without first

notifying the defendant's counsel, even when the

defendant's counsel has demanded that he be so

notified. Were we to adopt such a rule, it would

create a "new rule" of constitutional law under

Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288, 109 S.Ct. 1060,

103 L.Ed.2d 334 (1989) (per curiam), and its

progeny. Under Teague, a "new rule" is one which

was not "dictated by precedent existing at the

time the defendant's conviction became final."

Id. at 301, 109 S.Ct. at 1070; see also Graham

v. Collins, --- U.S. ----, ----, 113 S.Ct. 892,

897, 122 L.Ed.2d 260 (1993).

Unless a reasonable jurist

hearing petitioner's claim at the time his

conviction became final "would have felt

compelled by existing precedent" to rule in his

favor, we are barred from now doing so under the

edict of Teague and its progeny. Saffle v.

Parks, 494 U.S. 484, 488, 110 S.Ct. 1257, 1260,

108 L.Ed.2d 415 (1990); Graham, --- U.S. at

----, 113 S.Ct. at 898. We are not persuaded

that a reasonable jurist hearing Mann's claim at

the time his conviction became final would have

felt compelled to rule in his favor; accordingly,

we are barred from doing so.

B. Failure to Provide

Lesser Included Offense Instruction.

Mann next contends that his

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment rights were

violated when the state trial court refused a

requested jury instruction on the lesser

included offense of murder. In the seminal case

of Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625, 100 S.Ct.

2382, 65 L.Ed.2d 392 (1980), the Supreme Court

held that an instruction regarding a lesser

included offense is constitutionally required in

capital cases "when the evidence unquestionably

establishes that the defendant is guilty of a

serious, violent offense--but leaves some doubt

with respect to an element that would justify

conviction of a capital offense." Id. at 637,

100 S.Ct. at 2389.

Later, in Hopper v. Evans,

456 U.S. 605, 102 S.Ct. 2049, 72 L.Ed.2d 367

(1982), the Supreme Court clarified that "Beck

held that due process requires that a lesser

included offense instruction be given when the

evidence warrants such an instruction. But due

process requires that a lesser included offense

instruction be given only when the evidence

warrants such an instruction." Id. at 611, 102

S.Ct. at 2053.

Thus, our task is to

determine whether "the jury could rationally

acquit on the capital crime and convict for the

noncapital crime." Cordova v. Lynaugh, 838 F.2d

764, 767 (5th Cir.), cert. denied,

486 U.S. 1061 , 108 S.Ct. 2832, 100 L.Ed.2d

932 (1988); accord Hopper, 456 U.S. at

612, 102 S.Ct. at 2053; Keeble v. United States,

412 U.S. 205, 208, 93 S.Ct. 1993, 1995-96, 36

L.Ed.2d 844 (1973). We conclude that no rational

jury could have acquitted Mann on the capital

murder charge and convicted him on a noncapital

murder charge; thus, failure to provide an

instruction as to the lesser included offense of

murder did not violate Mann's constitutional

rights.

Mann was charged with the

capital crime of "intentionally commit[ting] [ ]

murder in the course of committing or attempting

to commit ... robbery." TEX.PENAL CODE ANN. Sec.

19.03(a)(2) (West 1994). Mann argues that a jury

could rationally have acquitted him of this

capital crime because the state failed to prove,

beyond a reasonable doubt, that the murder of

Bates occurred "in the course of committing or

attempting to commit ... robbery," within the

meaning of Sec. 19.03(a)(2). Specifically, Mann

contends that there is a reasonable doubt as to

whether the robbery of Matzig was "completed" by

the time Bates was murdered. We decline to

accept such a tortured interpretation of the

Texas statute.

The language "in the course

of" has been construed to mean conduct that

occurs in an attempt to commit, during the

commission, or in immediate flight after an

attempt or actual commission of robbery. Barnes

v. State, 845 S.W.2d 364, 367 (Tex.App.1992);

Fierro v. State, 706 S.W.2d 310, 313 (Tex.Crim.App.1986);

Riles v. State, 595 S.W.2d 858, 862 (Tex.Crim.App.1980)

(en banc); cf. TEXAS PENAL CODE ANN. Sec.

29.01(1) (West 1994) (providing an analogous

definition to the phrase "in the course of

committing theft"). Robbery, by statutory

definition, is essentially "theft plus"--namely,

it is theft accomplished by the use of physical

force or threats of bodily injury. See TEXAS

PENAL CODE ANN. Sec. 29.01(1) (West 1994).

Thus, in order for a murder

to be "in the course of" robbery it must be "in

the course of" committing a theft by force or

threats of bodily injury. Id. The key issue in

this case, therefore, is whether a rational jury

could have found that Mann was not "in the

course of committing theft" at the time of

Bates' murder.

Under either of two alternative, independent

grounds, we conclude that no rational jury could

find that the theft had been "completed" at the

time Bates was murdered.

First, the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals has construed the phrase "in

the course of" to include murder that occurs

during a continuous assaultive action, even if

the murder occurs at a different time or place

than the robbery:

[W]e cannot subscribe to the

Legislature an intent to provide for capital

murder ... only where the killing takes place at

the same place and about the same time of the

robbery and permit a defendant who has committed

a robbery to escape capital murder charges where

he removes the robbery victim from the scene and

takes him or her to another place and there

kills the victim to prevent the victim's

testimony.

Moore v. State, 542 S.W.2d

664, 675 (Tex.Crim.App.1976), cert. denied,

431 U.S. 949 , 97 S.Ct. 2666, 53 L.Ed.2d

266 (1977).

Furthermore, in Dorough v.

State, 639 S.W.2d 479, 480-81 (Tex.Crim.App.1982),

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals clarified

that when significant elements of the enumerated

felony continue uninterrupted, the enumerated

felony is kept "alive" for purposes of the

felony murder statute. Id. For example, in

Dorough, the continued use of force and threats

directed against a couple kept "alive" an

aggravated sexual assault for purposes of the

capital murder statute, despite the fact that

the murder occurred approximately 45 minutes

after the last sexual encounter. Id.

We think Moore and Dorough

make it unmistakably clear that Mann was "in the

course of" committing robbery when Bates was

murdered. Matzig was under forcible custody and

undoubtedly in fear of bodily injury at the time

of the murder. Thus, a significant element of

robbery--the use of force or threats--was

present at the time of the murder. There is no

reasonable doubt that the continuous assaultive

conduct kept the robbery of Matzig "alive" for

purposes of Mann's capital murder charge.

Mann contends that a rational

jury could have determined that the murder of

Bates was a mere "afterthought" unconnected to

the robbery. We need only note that this

contention is completely lacking in evidentiary

support. Indeed, Mann's own confession, which

was placed before the jury, flatly contradicts

this contention. The confession relates that

after driving around town attempting to cash

checks, Matzig asked Mann and Verbrugge if they

wanted to be dropped off anywhere, to which Mann

replied:

I told them no, and to drive

where I told them, because I knew the roads. And

[Verbrugge] raised up to the passenger seat and

told me--you know what we are going to have to

do. And I said, yea. Then [Matzig and Bates]

started to--they knew what we were going to do

and were saying--please don't do it to us, we

won't say nothing. Then I told him to stop the

jeep right there and told them to get out. Then

[Verbrugge] said you take care of them cause I

took care of the woman....

This evidence unequivocally

reveals that the murder of Bates was not a mere

"afterthought," but a coldly calculated attempt

to prevent future testimony. No rational jury

could have found otherwise on the evidence

before it.

Alternatively, Mann suggests

that the murder was intended to prevent

testimony regarding the rape or kidnapping--not

the robbery--and that such a motive would take

this case outside the ambit of Moore. We

disagree. Whether Mann's motive in killing Bates

was a desire to cover up the robbery, rape,

kidnapping--or some combination thereof--is

irrelevant. The key factor, according to Moore,

is that the murder occur for the purpose of

preventing testimony of the assaultive conduct

perpetrated against the victim.

The fact that a victim is

murdered in order to prevent testimony about

rape or kidnapping does not mean that the murder

did not occur "in the course of" a robbery. So

long as the murder was committed in the course

of the charged enumerated felony, it matters not

whether the murder was intended to silence

testimony about the specific felony charged or

another crime which occurred during the

continuous assaultive conduct.

A second, independent reason

for concluding that no rational jury could have

found the robbery had been "completed" at the

time of the murder is that the statute plainly

says otherwise. Under the Texas Penal Code,

robbery has five elements: (1) appropriation;

(2) of the property of another; (3) without the

owner's consent; (4) by force or threat of

imminent bodily injury; (5) with an intent to

permanently deprive. See TEXAS PENAL CODE ANN.

Secs. 29.02(a), 31.03(a).

When each of these elements

has occurred, the offense is ripe for purposes

of prosecution, One 1985 Chevrolet v. State, 852

S.W.2d 932 (Tex.1993); Barnes v. State, 824 S.W.2d

560 (Tex.Crim.App.1991); however, the elements

may be considered "ongoing" for purposes of the

capital felony murder statute. The question,

therefore, is whether any of these five elements

of robbery was "ongoing" at the time of Bates'

murder.

At least two of the elements

of robbery were "ongoing" at the time of Bates'

murder. First, as discussed earlier, the element

of force or threat of imminent bodily injury

continued up until the time of the murder. As

this significant element of robbery was

continuing at the time of the murder, the rule

of Moore and Dorough, supra, demands the

conclusion that the robbery had not ended.

Second, we believe the

element of appropriation was also continuing at

the time of the murder. Matzig's uncontroverted

testimony is that he wrote a check in the amount

of $1,000 which was to be cashed by Mann and

Verbrugge when the banks opened the following

morning. Thus, while Mann and Verbrugge

undoubtedly had the check in their physical

possession, the money represented by the check (i.e.,

$1,000 cash) was not in their control at the

time of the murder.

Thus, in order for the theft

of the $1,000 to be "completed," it was

necessary that Mann or Verbrugge cash the check

or deposit it into an account over which they

had control. See Evans v. State, 444 S.W.2d 641

(Tex.Crim.App.1969); Jones v. State, 672 S.W.2d

812 (Tex.Ct.App.1983), aff'd in part and rev'd

in part on other grounds, 672 S.W.2d 798 (Tex.Crim.App.1984);

White v. State, 632 S.W.2d 752 (Tex.Ct.App.1981).

Because the attempted

appropriation of the $1,000 was continuing at

the time of Bates' murder, the attempted robbery

was likewise ongoing. Thus, no rational jury

could conclude that the robbery had ended at the

time of the murder, and the murder was

accordingly committed "in the course of

committing or attempting to commit ... robbery"

within the meaning of the Texas capital murder

statute. TEX.PENAL CODE ANN. Sec. 19.03(a)(2).

C. Penry Claim.

In Penry v. Lynaugh, 492 U.S.

302, 109 S.Ct. 2934, 106 L.Ed.2d 256 (1989), the

Supreme Court held that the Texas capital

sentencing statute unconstitutionally prohibited

the jury from giving weight to Penry's

mitigating evidence of mental retardation. In

the present case, the district court, on the

recommendation of the magistrate, concluded that

Mann's Penry claim is procedurally barred for

his failure to place such evidence before the

jury during trial.

Mann argues that his Penry

claim is not procedurally barred because: (1)

the magistrate misunderstood prior Fifth Circuit

precedent on this issue; (2) even if the

magistrate did not misunderstand our precedents,

those precedents have incorrectly interpreted

Penry; and (3) the Texas sentencing statute is

unconstitutional as applied.

We turn first to the argument

that the magistrate below misunderstood our

prior decisions which have applied a procedural

bar to Penry claims when the petitioner has not

actually proffered the mitigating evidence

during trial. E.g., Motley v. Collins, 18 F.3d

1223, 1228 (5th Cir.1994); Black v. Collins, 962

F.2d 394, 407 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, --- U.S.

----, 112 S.Ct. 2983, 119 L.Ed.2d 601 (1992);

Lincecum v. Collins, 958 F.2d 1271, 1282 (5th

Cir.), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 113 S.Ct.

417, 121 L.Ed.2d 340 (1992); Barnard v. Collins,

958 F.2d 634, 637 (5th Cir.1992), cert. denied,

--- U.S. ----, 113 S.Ct. 990, 122 L.Ed.2d 142

(1993); Wilkerson v. Collins, 950 F.2d 1054,

1061 (5th Cir.1992), cert. denied, --- U.S.

----, 113 S.Ct. 3035, 125 L.Ed.2d 722 (1993);

May v. Collins, 904 F.2d 228, 232 (5th

Cir.1990), cert. denied,

498 U.S. 1055 , 111 S.Ct. 770, 112 L.Ed.2d

789 (1991); DeLuna v. Lynaugh, 890 F.2d

720, 722 (5th Cir.1989).

Specifically, Mann contends

that the first case to apply this procedural bar

to a Penry claim, DeLuna v. Lynaugh, 890 F.2d

720 (5th Cir.1989), has been impermissibly

broadened by May and its progeny. According to

Mann, DeLuna was meant to stand for the narrow

proposition that decisions not to introduce

mitigating evidence based upon considerations

other than the Hobson's Choice posed by the

Texas sentencing statute will be procedurally

barred.

While it is true that the

decision to keep mitigating evidence away from

the jury in DeLuna was based upon trial

counsel's fear that such evidence would "open

the door" to evidence of the accused's prior

criminal record, DeLuna, 890 F.2d at 722,

nothing in DeLuna itself or our subsequent cases

has so limited it. Indeed, our subsequent

decisions embodied in May and its progeny have

made it clear that any Penry claim will be

procedurally barred if the mitigating evidence

is not actually proffered at trial. Motley, 18

F.3d at 1228; Black, 962 F.2d at 407; Lincecum,

958 F.2d at 1282; Barnard, 958 F.2d at 637;

Wilkerson, 950 F.2d at 1061; May, 904 F.2d at

232.

Mann also contends that the

magistrate's analysis of his Penry claim is

defective because it relied upon prior decisions

of this court that he claims have impermissibly

narrowed Penry. Even assuming arguendo that the

magistrate or district court relied on other

cases besides DeLuna and May and their progeny,

we need not address this issue because we find

that the procedural bar just discussed is an

adequate ground for deciding this issue.

Mann's final contention

regarding his Penry claim is that the Texas

sentencing statute is unconstitutional as

applied to him because it "chilled" his ability

to provide the jury with mitigating evidence of

his low intelligence and abusive childhood. This

"chilling" effect springs from the fact that

under the Texas capital sentencing statute, some

evidence is "double edged"--i.e., the evidence

may be simultaneously mitigating and aggravating

because it may make it more likely that the jury

will answer "yes" regarding the special issues.

Mann contends that this

Hobson's Choice dilemma violated his right to

due process. We have previously declined

invitations to declare the Texas sentencing

statute unconstitutional because of such an

alleged "chilling effect." See Lackey v. Scott,

28 F.3d 486, 490 (5th Cir.1994); Andrews v.

Collins, 21 F.3d 612, 630 (5th Cir.1994); Black

v. Collins, 962 F.2d 394, 407 (5th Cir.1992);

May v. Collins, 948 F.2d 162, 167-68 (5th

Cir.1991). We continue to adhere to our

statement in Andrews that "a constitutional

violation does not result simply because the

Texas death penalty scheme triggers certain

tactical choices on the part of counsel."

Andrews, 21 F.3d at 630.

D. Juror Exclusion.

Mann asserts that the state

trial court improperly excluded four jurors for

cause because they voiced emotional opposition

to the death penalty. Specifically, Mann asserts

that permitting exclusion in these circumstances

violated the rule of Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776

(1968), and Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 100

S.Ct. 2521, 65 L.Ed.2d 581 (1980).

The magistrate and the

district court both rejected this argument on

grounds that the state trial court's decision to

exclude jurors for their views on capital

punishment is entitled to a presumption of

correctness which Mann had not overcome. Mann v.

Lynaugh, 688 F.Supp. 1121, 1123-24 (N.D.Tex.1987);

see also Wainwright v. Witt,

469 U.S. 412 , 429, 105 S.Ct. 844, 854-55,

83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985) (holding that a

trial judge's decision to exclude jurors based

upon their views of capital punishment is

entitled to Sec. 2254(d)'s presumption of

correctness).

Under the rule of Wainwright,

the decisive question is "whether the juror's

views would 'prevent or substantially impair the

performance of his duties as a juror in

accordance with his instructions and his oath.'

" Id. at 424, 105 S.Ct. at 852 (quoting Adams v.

Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 45, 100 S.Ct. 2521, 2526, 65

L.Ed.2d 581 (1980)).

The gravamen of Mann's

complaint is that the prosecutor's use of a

hypothetical "intellectual/emotional dilemma"

during voir dire misled the potential jurors

into believing that emotional opposition to the

death penalty would render them unable to uphold

their oath as jurors. Under this line of

questioning, the prosecutor told the prospective

jurors that they would be required to take the

following oath:

You and each of you do

solemnly swear that in the case of The State of

Texas against the defendant, you will a true

verdict render according to the law and the

evidence, so help you God.

TEX.CODE CRIM.PROC.ANN. art.

35.22 (West 1989).

The prosecutor asked the

prospective jurors if they would be able to

impose the death penalty if they emotionally

believed that Mann did not deserve to die but

intellectually they knew the evidence required

that the special issues should be answered

affirmatively. Each of the four excluded venire

members informed the prosecutor that faced with

such a dilemma, they would not be able to take

the oath.

The prosecutor challenged each of these jurors

for cause, and the trial court excused them.

Mann specifically contends

that in upholding the trial court's exclusion,

the magistrate and the district court failed to

consider Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 100 S.Ct.

2521, 65 L.Ed.2d 581 (1980), and Witherspoon v.

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d

776 (1968). In Witherspoon, the Court held that

the state has no valid interest in excluding a

juror for "any broader basis" than an inability

to follow the law or abide by their oaths.

Witherspoon, 391 U.S. at 522 n. 21, 88 S.Ct. at

1777 n. 21. The Court made it clear, however,

that

nothing we say today bears

upon the power of a State to execute a defendant

sentenced to death by a jury from which the only

veniremen who were in fact excluded for cause

were those who made unmistakably clear (1) that

they would automatically vote against the

imposition of capital punishment without regard

to any evidence that might be developed at the

trial of the case before them, or (2) that their

attitude toward the death penalty would prevent

them from making an impartial decision as to the

defendant's guilt.

Id.

In Adams, the Court

overturned a death sentence because potential

jurors had been excluded for admitting that

their opposition to the death penalty would

render them unable to take the then-existing

Texas jury oath which required:

A prospective juror shall be

disqualified from serving as a juror unless he

states under oath that the mandatory penalty of

death or imprisonment for life will not affect

his deliberations on any issue of fact.

TEX.PENAL CODE ANN. Sec.

12.31(b) (1974) (repealed).

The constitutional infirmity

in Adams was with the oath itself, which by its

terms prohibited jurors from taking account of

their emotions in deciding issues of fact. The

Adams Court made it clear, however, that the

state has a "legitimate interest in obtaining

jurors who [can] follow their instructions and

obey their oaths," Adams, 448 U.S. at 44, 100

S.Ct. at 2526 (emphasis added), provided, of

course, that the oath itself is not

constitutionally defective. The Court recognized

that, given a properly worded oath, the Texas

scheme would be constitutionally acceptable:

[i]f the juror is to obey his

oath and follow the law of Texas, he must be

willing not only to accept that in certain

circumstances death is an acceptable penalty but

also to answer the statutory questions without

conscious distortion or bias. The State does not

violate the Witherspoon doctrine when it

excludes potential jurors who are unable or

unwilling to address the penalty questions.

Id. at 46, 100 S.Ct. at 2527.

We think Witherspoon and

Adams make it unmistakably clear that it is

constitutionally permissible to exclude a venire

member for cause when it is clear that she

cannot faithfully render a verdict according to

the evidence. If state law mandates the

imposition of the death penalty under certain

circumstances and the state proves those

circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt, a

juror's emotional opposition to capital

punishment may, in certain instances, distort

her ability to uphold the law.

While it is true, as Adams

makes clear, that mere emotional opposition to

capital punishment alone is insufficient cause

for juror exclusion, it is equally clear that

emotional opposition may rise to the level where

it interferes with a potential juror's ability

to sit as a dispassionate and objective arbiter

of justice. If a prospective juror's emotional

opposition is so severe that it compels her to

ignore the law or disables her from answering

the statutory questions without conscious

distortion or bias, exclusion for cause is

proper. Adams, 448 U.S. at 50, 100 S.Ct. at

2528-29.

Under the facts of this case,

we agree with the district court's conclusion

that the presumption of correctness of the trial

court's exclusion of these four jurors has not

been overcome. The prosecutor's "intellectual/emotional

dilemma," while certainly no model of clarity,

did manage to convey to the prospective jurors a

correct interpretation of the Texas capital

sentencing statute. A venire member who cannot

answer the special issues "yes" despite the fact

that the evidence requires a "yes" answer is, by

definition, unable to render a verdict "according

to the law and the evidence" as required by the

Texas oath.

Furthermore, as the Supreme

Court stated in Witt:

What common sense should have

realized experience has proven; many veniremen

simply cannot be asked enough questions to reach

the point where their bias has been made "unmistakably

clear"; these veniremen may not know how they

will react when faced with imposing the death

sentence, or may be unable to articulate, or may

wish to hide their true feelings. Despite this

lack of clarity in the printed record, however,

there will be situations where the trial judge

is left with the definite impression that a

prospective juror would be unable to faithfully

and impartially apply the law.... [T]his is why

deference must be paid to the trial judge who

sees and hears the jurors.

Witt, 469 U.S. at 424-26, 105

S.Ct. at 852.

The state trial judge in

Mann's case was in a far better position than we

to draw conclusions about the potential jurors'

ability to render a verdict in accordance with

the law and evidence. The record reveals that he

posed several questions of his own to the

excluded venire members before excusing them for

cause.

He determined, based upon

their answers and demeanor, that they were not

qualified to serve because their opposition to

the death penalty would render them unable to

keep their oath. Such credibility determinations

are more appropriately resolved under the

watchful eye of the trial judge than by an

appellate court staring at a cold record, which

is precisely why they are accorded a presumption

of correctness under Sec. 2254(d). Mann has not

overcome this presumption; therefore, his claim

must fail.

E. Prosecutorial

Definition of "Deliberate."

Mann argued that the

prosecutor misled a juror during voir dire that

the term "deliberate" (the requisite mental

state required under the first special issue of

the Texas capital sentencing statute) was

synonymous with the term "intentional" (the

requisite mental state required for capital

murder). He maintains that the prosecutor's

statements violate the rule of Lane v. State,

743 S.W.2d 617 (Tex.Crim.App.1987).

The state trial court, in

considering Mann's second habeas petition,

concluded that this claim was barred for three

reasons: (1) failure of Mann's counsel to

contemporaneously object; (2) failure of Mann's

counsel to attempt to correct the prosecutor's

alleged misstatement; and (3) on the merits, the

statements did not mislead the juror.

The Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals agreed, stating that "the findings and

conclusions entered by the trial court are

supported by the record." The district court

also concluded that the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule procedurally bars Mann from

raising this claim. Mann argues that he is not

procedurally barred because his pretrial motion

adequately apprised the trial court of the

gravamen of his objection.

We agree with the state

courts and the district court that Mann has

waived his claim by his failure to

contemporaneously object.

See Perry v. State, 703 S.W.2d 668, 670 (Tex.Crim.App.1986)

("The failure of the appellant to complain or

object in the trial court constitutes a

procedural default under [Texas] law."); accord

TEX.R.APP.P. 52(a). Mann's pretrial motion was

inadequate to place the trial court on notice

that Mann was objecting to the prosecutor's

equation of the terms "deliberate" and "intentional."

His pretrial motion made only

two arguments: (1) that the Texas capital

sentencing statute is unconstitutionally vague;

and (2) that the statute fails to adequately

define the terms "deliberately," "probability,"

"criminal acts of violence," and "constitute a

continuing threat to society," thereby rendering

counsel's assistance per se ineffective and

permitting arbitrary imposition of the death

penalty. The trial court denied this motion.

Mann's pretrial motion

mounted a constitutional attack on the Texas

sentencing statute itself; it did not alert the

trial court to the issue now being raised on

appeal--namely, whether the prosecutor's

comments violated the rule of Lane v. State, 743

S.W.2d 617 (Tex.Crim.App.1987). Thus, the

contemporaneous objection rule blocks

consideration of his claim on appeal.

Mann next contends that the

contemporaneous objection rule cannot bar our

review of his claim on the merits because it is

not "strictly and regularly followed." See, e.g.,

Ford v. Georgia, 498 U.S. 411, 423, 111 S.Ct.

850, 857, 112 L.Ed.2d 935 (1991); Johnson v.

Mississippi, 486 U.S. 578, 587, 108 S.Ct. 1981,

1987, 100 L.Ed.2d 575 (1988); Wilcher v. Hargett,

978 F.2d 872, 879 (5th Cir.1992), cert. denied,

--- U.S. ----, 114 S.Ct. 96, 126 L.Ed.2d 63

(1993).

We need not decide this issue

at this time. Even assuming arguendo that the

Texas contemporaneous objection rule is not

strictly and regularly followed, Mann's claim

fares no better when analyzed on the merits. The

prosecutor in this case did not intimate that "intentional"

and "deliberate" are synonymous. In fact, the

prosecutor never even used the term "intentional"

in his exegesis of the term "deliberate." The

complained of prosecutorial statement is as

follows:

Now, the judge isn't going to

tell you what the word "deliberately" means. It

doesn't have any special meaning with regard to

this question. It means the same thing when you

or I use it in daily language.

You've probably heard one of

your little boys say to the other one, "Well,

you did that deliberately." Well, it means the

same thing. You did it on purpose, you did it--it

wasn't an accident.

This statement conveyed to

the juror that "deliberate" requires something

more than a voluntary physical act, something

akin to conscious purpose. See Fearance v.

State, 620 S.W.2d 577, 584 (Tex.Crim.App.) (en

banc) (holding that the term "deliberately" as

used in capital sentencing statute is "the

thought process which embraces more than a will

to engage in conduct and activates the

intentional conduct."), cert. denied,

454 U.S. 899 , 102 S.Ct. 400, 70 L.Ed.2d

215 (1981).

Indeed, the prosecutor's

comment in this case echoes our conclusion in

Milton v. Procunier, 744 F.2d 1091, 1096 (5th

Cir.1984), cert. denied,

471 U.S. 1030 , 105 S.Ct. 2050, 85 L.Ed.2d

323 (1985), that the jurors, in the

context of a specific case, could not reasonably

assign different meanings to the word "deliberate."

As such, the prosecutor's comments conveyed a

correct interpretation of Texas law and Mann's

contention is therefore without merit.

F. Ineffective Assistance

of Counsel.

Mann contends that the

failure of his trial counsel to develop and

offer the "double-edged" mitigating evidence of

low intelligence and an abusive childhood

rendered his counsel ineffective in violation of

the Sixth Amendment. We disagree.

The standard for assessing

the effectiveness of counsel was announced in

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct.

2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984). Strickland requires

the defendant to prove two things: (1) counsel's

performance was deficient under an objective

standard of reasonableness, id. at 687-88, 104

S.Ct. at 2064-65, and (2) that "there is a

reasonable probability that, but for counsel's

unprofessional errors, the result of the

proceeding would have been different." Id. at

694, 104 S.Ct. at 2068.

When assessing whether an

attorney's performance was deficient, we "must

indulge a strong presumption that counsel's

conduct falls within the wide range of

reasonable professional assistance." Id. at 689,

104 S.Ct. at 2065; Andrews v. Collins, 21 F.3d

612, 621 (5th Cir.1994).

To demonstrate prejudice, the

defendant must prove that there is a "reasonable

probability that, absent the errors, the

sentencer ... would have concluded that the

balance of aggravating and mitigating

circumstances did not warrant the death

penalty." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 695, 104 S.Ct.

at 2069; Andrews, 21 F.3d at 622.

In this case, Mann's trial

counsel admitted in an affidavit that he made a

strategic decision not to introduce evidence of

his low intelligence or abusive childhood

because such evidence had a "double-edged"

nature which may have harmed Mann's case. Such

strategic decisions are "granted a heavy measure

of deference in a subsequent habeas corpus

attack." Wilkerson v. Collins, 950 F.2d 1054

(5th Cir.1992) (citing Strickland, 466 U.S. at

690-91, 104 S.Ct. at 2065-67), cert. denied, ---

U.S. ----, 113 S.Ct. 3035, 125 L.Ed.2d 722

(1993).

Under an objective standard

of reasonableness, such a sound tactical

decision does not constitute deficient

performance. See Sawyers v. Collins, 986 F.2d

1493, 1505-06 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, --- U.S.

----, 113 S.Ct. 2405, 124 L.Ed.2d 300 (1993).

Mann has not overcome the strong presumption

that this strategic decision was unreasonable

under the circumstances; thus, he has not

satisfied the deficiency prong of Strickland.

Even assuming, arguendo, that

Mann's counsel was deficient, we find that Mann

has failed to show the existence of evidence of

sufficient quality and force which, if

introduced, would have more likely than not

persuaded the jury that the death penalty was

unwarranted.

Callins v. Collins, 998 F.2d 269, 279 (5th

Cir.1993), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 114 S.Ct.

1127, 127 L.Ed.2d 435 (1994); Wilkerson v.

Collins, 950 F.2d at 1065. Thus, Mann has also

failed to satisfy the prejudice prong of

Strickland. When either prong of Strickland is

not proven, the petitioner is not entitled to

relief. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687, 104 S.Ct.

at 2064.

G. Caldwell v. Mississippi

Claim.

Near the end of his closing

argument of the punishment phase, the prosecutor

in Mann's case told the jury:

When is Fletcher Mann going

to stop hurting women, young women and old women?

When is he going to stop raping them, robbing

them, hurting people? When is he going to stop

hurting jailers? Huh? When is he going to stop

hurting inmates, have you thought about that?

I'll tell you: when he is executed. And not

before. And I tell you, the only shame in our

system is that he's not going to be executed

tonight after you answer the three questions,

because that's what he deserves. But we know

better than that, don't we? But he deserves to

be executed tonight.

Mann contends that this

argument violated the rule of Caldwell v.

Mississippi, 472 U.S. 320, 105 S.Ct. 2633, 86

L.Ed.2d 231 (1985), because it diminished the

jury's sense of responsibility for its

sentencing determination. Specifically, Mann

contends that the phrase, "But we know better

than that, don't we?" suggested to the jury that

their sentence would be subject to appellate

review, thereby relieving them of fears that

they would provide the "last word" on Mann's

sentence and making it more likely that they

would impose the death penalty.

In Caldwell, the Supreme

Court held that the following statement by the

prosecution violated the Eighth Amendment

because it undermined "reliable exercise of jury

discretion":

Now, [the defense] would have

you believe that you're going to kill this man

and they know--they know that your decision is

not the final decision. My God, how unfair can

they be? Your job is reviewable. They know it.

Id. at 325, 329, 105 S.Ct. at

2637, 2639.

While we do not endorse the

prosecutor's arguments in this case as a model

of propriety, we do not believe they rise to the

level of a Caldwell violation. The statement, "But

we know better than that, don't we?" is

ambiguous at best. A juror hearing such a remark

was not likely left with the impression that her

sentencing decision was not one of life and

death. By contrast, there was no mistaking the

import of the prosecutor's remarks in Caldwell.

Thus, we conclude that the prosecutor's comments

did not "affect the fundamental fairness of the

sentencing proceeding [so] as to violate the

Eighth Amendment." Id. at 340, 105 S.Ct. at

2645.H. Failure to Hold an Evidentiary Hearing.

Mann's final contention is

that the district court erred in not holding an

evidentiary hearing on his habeas petition.

Specifically, Mann contends that a hearing was

necessary to adequately consider his newly

discovered mitigating evidence of low

intelligence and an abusive childhood.

The Supreme Court has held

that a habeas petitioner is entitled to an

evidentiary hearing in federal court regarding a

claim which was not developed in the state

courts only upon a showing of cause and

prejudice. Keeney v. Tamayo-Reyes, --- U.S.

----, 112 S.Ct. 1715, 118 L.Ed.2d 318 (1992).

Under this standard, the

habeas petitioner bears the burden of

establishing both cause for his failure to

develop the facts in state court, as well as

actual prejudice. Id. at ----, 112 S.Ct. at

1719. This stringent standard is designed to

further the interests of comity and judicial

economy. Id. An exception from the cause and

prejudice standard may be made only if the

petitioner can show that a fundamental

miscarriage of justice would result from the

failure to hold a federal evidentiary hearing.

Id. at ----, 112 S.Ct. at 1721.

Mann's entire argument on

this issue consists of generalized assertions of

unfairness

and citation to one case, Wilson v. Butler, 813

F.2d 664 (5th Cir.1987), cert. denied,

484 U.S. 1079 , 108 S.Ct. 1059, 98 L.Ed.2d

1021 (1988).

Wilson, however, is

distinguishable because it involved a claim of

ineffective assistance of counsel in violation

of the Sixth Amendment, and we merely held that

ineffective assistance would be sufficient cause

to warrant an evidentiary hearing provided the

petitioner has also established prejudice. Id.

at 671-73. In this case, by contrast, Mann does

not allege that ineffective assistance of

counsel caused his failure to develop the

mitigating evidence in state court.

In fact, Mann proffers no

reason whatsoever for his failure to develop

this evidence. Furthermore, we note that Mann

has not attempted to establish prejudice; he

offers no explanation as to how an evidentiary

hearing would have altered the outcome of his

petition. As Mann has failed to establish either

cause or prejudice as required by Tamayo-Reyes,

we conclude that the district court did not err

in failing to hold an evidentiary hearing.

V. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, we

AFFIRM the judgment of the district court.

*****

(a) A person commits an

offense if he commits murder as defined under

Section 19.02(b)(1) and:

....

(2) the person

intentionally commits the murder in the course

of committing or attempting to commit kidnapping,

burglary, robbery, aggravated sexual assault,

arson, or obstruction or retaliation....

TEX.PENAL CODE ANN. Sec.

19.03 (West 1994).

Procedure in a capital case

(a) Upon a finding that the

defendant is guilty of a capital offense, the

court shall conduct a separate sentencing

proceeding to determine whether the defendant

shall be sentenced to death or life imprisonment.

The proceeding shall be conducted in the trial

court before the trial jury as soon as

practicable. In the proceeding, evidence may be

presented as to any matter that the court deems

relevant to sentence. This subsection shall not

be construed to authorized the introduction of

any evidence secured in violation of the

Constitution of the United States or of the

State of Texas. The state and the defendant or

his counsel shall be permitted to present

argument for or against sentence of death.

(b) On conclusion of the

presentation of the evidence, the court shall

submit the following issues to the jury:

(1) whether the conduct of

the defendant that caused the death of the

decedent was committed deliberately and with the

reasonable expectation that the death of the

deceased or another would result;

(2) whether there is a

probability that the defendant would commit

criminal acts of violence that would constitute

a continuing threat to society; and

(3) if raised by the

evidence, whether the conduct of the defendant

in killing the deceased was unreasonable in

response to the provocation, if any, by the

deceased.

....

(e) if the jury returns an

affirmative finding on each issue submitted

under this article, the court shall sentence the

defendant to death. If the jury returns a

negative finding on any issue submitted under

this article, the court shall sentence the

defendant to confinement in the Texas Department

of Corrections for life....

TEX.CODE CRIM.PROC.ANN. art.

37.071 (West 1981).

It should be noted that

article 37.071 has since been revised, but the

revisions apply only to offenses committed after

September 1, 1991. See TEX.CODE CRIM.PROC.ANN.

art. 37.071(i) (West Supp.1994).

I am giving this statement to

J.M. Gholston I.D. 2297, who has identified

himself as Peace Officer of the City of Dallas,

Texas, and he has duly warned me that I have the

following rights: that I have the right to

remain silent and not make any statement at all;

that any statement I make may be used against me

at my trial; that any statement I make may be

used as evidence against me in court; that I

have the right to have a lawyer present to

advise me prior to and during any questioning;

that if I am unable to employ a lawyer, I have

the right to have a lawyer appointed to advise

me prior to and during any questioning and that

I have the right to terminate the interview at

any time.

Prior to and during the

making of the statement, I have and do hereby

knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily waive

the above explained rights and I do make the

following voluntary statement to the

aforementioned person of my own free will and

without any promises or offers of leniency or

favors, and without compulsion or persuasion by

any person or persons whomsoever:

....

Q. All right. Now, when you

say I don't think I could, I know that's just a

way of saying it, but we need something clear

and unequivocal. Are you saying, "I could not

take that oath"? Because if you can take the

oath to base your verdict strictly on the

evidence, then we're right back to square one.

See, if you can take the oath

to base your verdict just on the evidence, then

you're saying that "Even though I feel like he

should not die, I can go on and answer the

question. I can compute the answers and come up

with them and reach them."

So if you tell us that you

cannot take that oath, then you're not qualified

and that would be--that would be it.

A. I can't take that oath.

Q. Fine. Are you firm and

fixed on that, then?

A. Yes.

....

Q. And so that no matter what

degree of evidence they produced you could never

answer the question "yes"?

A. If I thought he should

live and be imprisoned, I could not give him the

death penalty.