|

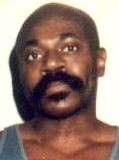

Clemency Petition of Ernest Martin

APPLICATION FOR EXECUTIVE CLEMENCY FOR ERNEST MARTIN

FEBRUARY 25, 2003

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………. 1

II. Ernest Martin’s Death Sentence Constitutes Disproportionate

Punishment

1. Ernest Martin, and this offense, are not the “worst of the worst”………………….

3

A. Ernest Martin

i) Youthfulness at time of offense……………………………………………… 3

ii) Lack of history of violence …………………………………………………. 4

iii) History of dual diagnoses – psychological disorder and mental

retardation .. 4

B. Offense

i) Plan was to rob, premeditation for murder lacking …………………………. 8

ii) Victim was shot at night through a door ……………………………………. 9

III. Ernest Martin’s Death Sentence Constitutes Unequal Justice,

Particularly Considering His Accomplice Received No Punishment

Whatsoever ……………… 9

1) Accomplice/state witness Josephine Pedro got off “scot-free”

while Ernest Martin received the death penalty …………………………………………………..

………… 9

2) Ernest Martin has already spent 20 years in prison for the

offense ………….. …… 11

IV. Ernest Martin’s 1983 Death Sentence Resulted From An Unfair And

Unreliable Process

1. Ohio Death Penalty Law new in 1983 ……………………………………………… 12

2. Inexperience of trial court led to shoddy, unreliable proceedings…………………..

13

3. Inexperience of defense counsel led to poor representation

…….………………… 14

4. Resulting verdict and death sentence unreliable (lingering doubts

of guilt) ……… 19

V. Role of Clemency ……………………………………………………………………. 23

VI. Totality of Circumstances Warrant Granting of Clemency ………………………

25

VII. Clemency Request …………………………………………………………………… 26

I. Introduction

Death is not the appropriate sentence for Ernest Martin. Ernest is

not among the “worst of the worst” offenders, and his offense,

although tragic, is not among the “worst of the worst” crimes. His

sentence of death is an egregious example of disproportionate

punishment and unequal justice. This is especially true in light of

the fact that the accomplice to the offense received absolutely no

punishment whatsoever.

Ernest is not among the “worst of the worst” offenders because:

1) he was young, only 22 years old, at the time of the offense; 2)

he did not have a significant criminal history of being physically

violent toward others; 3) he has suffered in life from a significant

psychological disorder; and 4) he has a significant family history

of, and has himself suffered from, serious developmental

disabilities inclusive of mental retardation.

This offense is not among the “worst of the worst” offenses

because: 1) the evidence indicates there was no plan to commit

murder; and 2) it is highly questionable whether the perpetrator

actually intended to kill the victim when the lethal shot was fired

through a door at night.

Ernest Martin’s sentence of death is grossly unjust when compared

to the fact that the accomplice, Josephine Pedro, went unpunished in

trade for testifying for the prosecution. Ms. Pedro confessed to her

crucial role in the crime, a role corroborated by another state

witness who said Ms. Pedro had as much to do with the robbery as did

Ernest. Yet, while Ernest received the ultimate sanction, Ms. Pedro,

accomplice to the murder, walked away free. This unjust and

disparate result is virtually incomprehensible. It is most likely

due, however, to the abysmal performance by Ernest’s court-appointed

counsel.

All indications are that counsel was hoping for a plea-bargain

and were thus totally unprepared when the case went to trial.

Counsel presented absolutely no evidence in defense, choosing simply

to rest at the close of the prosecution’s case. Most significantly,

counsel failed to present lone eye-witness E.J. Rieves-Bey, whose

statements were favorable to the defense. Mr. Rieves-Bey was

critical because he was the only witness who observed the gunman

running away from Mr. Robinson’s store after the shots were fired.

Mr. Rieves-Bey consistently stated that Ernest Martin was not the

gunman. Defense counsel failed to ensure Mr. Rieves-Bey’s presence,

inexplicably relying on prosecutor Carmen Marino to subpoena him to

trial.

Defense counsel likewise performed deplorably at Ernest Martin’s

mitigation hearing, where they did more harm to their client than

good. Their representation was so deficient that the trial judge

felt compelled to take over the hearing, calling out into the

courtroom audience searching for volunteers to come up and testify

on Ernest’s behalf. This stunning departure from proper procedures

created the harmful appearance that even Ernest’s own family members

had nothing good to say about him.

Undoubtedly, contributing to defense counsel’s appalling

performance was their inexperience under the new capital statute.

Ernest’s case was one of the earliest to be tried under Ohio’s new

death penalty scheme. Consequently all parties involved lacked

experience with the laws and proper procedures. This inexperience

resulted in deficiencies and irregularities in the proceedings that

contributed significantly to the manifest injustice Ernest incurred.

Ernest Martin should not have to pay with his life simply because

his trial occurred under these circumstances.

For these reasons, and the reasons more fully presented below,

Ernest Martin’s death sentence should not be countenanced by the

State of Ohio. In the interests of justice and mercy, Ernest Martin

pleads for a recommendation of clemency by the Parole Board in the

form of commutation of his sentence.

II. Ernest Martin’s Death Sentence Constitutes Disproportionate

Punishment

1. Ernest Martin, and this offense, are not the “worst of the

worst”

Virtually all of society agrees that if the government chooses to

impose capital punishment, such punishment should be reserved for

the “worst of the worst” criminals – i.e., those who commit the most

heinous and reprehensible of crimes and those who are considered by

society to be the most blameworthy. Ernest Martin does not fall into

the category of the “worst of the worst” criminals. This offense

does not fall into the category of the “worst of the worst”

offenses.

A. Ernest Martin

i) Youthfulness at time of offense

Ernest Martin was young, only 22 years of age, at the time of the

instant offense. His youthfulness should be considered as a factor

weighing in favor of mercy and the granting of clemency. This is

particularly true here, where -- assuming his involvement in the

offense -- his immaturity and concomitant proclivity for rash

behavior were likely contributing factors in the shooting that

occurred.

Youth of the offender is legally recognized as a mitigating

factor under Ohio’s death penalty statutory scheme. Ohio Revised

Code Section 2929.04, which sets forth the legal criteria for

imposition of a death sentence, lists seven (7) factors that are to

be considered by the court or trial jury as weighing in mitigation

of the offense. The factor listed as number four (4) is “[t]he youth

of the offender.”

Ernest Martin was a young man back in January of 1983. He is now

42 years old. He has matured and, like anyone who has aged twenty

years, is a very different person today than he was then. His

youthfulness at the time should be taken into account by this Board

in its consideration of clemency.

ii) Lack of history of violence

Ernest Martin’s life history and prior record do not reflect a

depraved human being deserving society’s most severe punishment. His

past criminal record is relatively short and demonstrates very

little history of violence.

As can be seen from the trial court’s sentencing opinion,

Ernest’s juvenile offenses were not serious. Of his three juvenile

convictions, one involved breaking a window worth only $6.50 (six

dollars and fifty cents), and another involved a theft of a $15

watch. The third conviction was for operating an automobile without

the owner’s permission. None of these offenses involved any physical

violence of any kind.

Ernest’s adult record also does not reflect that of a hard-core

criminal. Prior to the instant offense Ernest was convicted on three

occasions. One conviction was for receiving stolen property, another

was for carrying a concealed weapon, and the third was for an

assault. The assault is the only conviction on either Ernest

Martin’s juvenile or adult record that is an offense involving

physical violence. Even that offense, however, is somewhat

misleading, as it involved a fight with a neighbor over windows

being broken out of the Martin’s car. Ernest has always maintained

that the neighbor instigated the fight.

Ernest’s record does not depict a violent human being, let alone

a cold-blooded killer. The subject offense of 1983 was not within

his character. His lack of a violent history or violent nature

presents a strong reason for the recommendation of clemency.

iii) History of dual diagnoses - psychological disorder and

mental retardation

Ernest’s background reveals an individual who, along with being born

into a chaotic, unstable home environment lacking the presence of a

positive male role model, suffered from significant psychological

problems. In addition, he suffered from a mental disability along

the lines of mild mental retardation. Because these deficits were

not chosen by Ernest but instead were thrust upon him, particularly

the mental deficits which appear to be hereditary, Ernest is less

worthy of blame than the common criminal offender.

There appears to be a societal concensus that disfavors executing

an individual who suffers from mental illness or mental retardation.

For instance, a year 2002 Gallup poll shows that while the majority

of American citizens favor capital punishment, they are not in favor

of executing individuals who are either mentally ill or mentally

retarded. See Appendix, exhibit 1. This survey demonstrates that 75%

of United States adults oppose imposition of the death upon the

mentally ill. A resounding 82% of the adult population opposes

imposition of the death penalty upon the mentally retarded. In light

of such figures, it is not surprising that the United States Supreme

Court recently held that execution of an individual with mental

retardation (whether in the form of mild, moderate, or profound)

violates the United States Constitution.1

In Ohio, a mentally retarded person is defined as a person having

significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning existing

concurrently with deficiencies in adaptive behavior, manifested

during the development period. The Supreme Court of the United

States recognized the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR)

and American Psychiatric Association definitions of mental

retardation. The AAMR classifies mental retardation as

“characterized by significant subaverage intellectual functioning,

existing concurrently with related limitation in two or more of the

following adaptive areas: communication, self-care, home living,

social skills, community use, selfdirection, health and safety,

functional academics, leisure and work. Mental retardation manifests

itself before age 18.”3

Ernest began exhibiting behavioral and developmental problems at

an early age. According to family members, when Ernest was nine or

ten years old, teachers at school began expressing concern about him

still sucking his thumb and giving limited responses in class. At

the age of thirteen Ernest was referred by the school psychologist

at Woodland Hills Elementary School to the Child Guidance Center in

Cleveland for psychiatric evaluation. He was placed into counseling

sessions as treatment. It was noted at this time (age 13) that

Ernest was still wetting his bed. Based on a previous assessment by

psychologist Nancy Schmidtgoessling, Ernest likely suffers from

borderline personality disorder. See Appendix, exhibit 2. An

individual with this diagnosis is known to exhibit, among other

symptoms, “transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe

dissociative symptoms.”4 The term “borderline” is used in this

diagnosis because the disorder involves components of psychosis and

borders on what is referred to in the mental health field as an Axis

1 diagnosis.

3 Mental Retardation: Definition, Classification and Systems of

Supports 5 (9th ed. 1992); Atkins, 122 S.Ct. 2242, 2245, n. 3. 4 See

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV of the American Psychiatric

Association, 1994 ed. 5 Ernest Martin’s claim regarding mental

retardation as a basis for vacating his death sentence is currently

pending in state court. On February 24, 2003, a successor petition

was filed in the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas, along with a

motion for a stay of execution in the Ohio Supreme Court, seeking to

vacate his sentence

Ernest’s mental retardation5

In the 5th grade Ernest was placed in special classes labeled “EMR”

– classes for the Educable Mentally Retarded. See Appendix, exhibit

2 (affidavit of mitigation specialist Pam Swanson). At that time

Ernest’s IQ tested at 77. Id.; see also Appendix, exhibit 36 (affidavit

of Dr. David Hammer, attached to Ernest Martin’s February 24, 2003

successor petition to vacate judgment based on his mental

retardation). His placement in EMR classes signifies that early in

his life Ernest was diagnosed by educators as being mentally

retarded. Ernest has also been tested, as an adult, as having the

intellectual functioning level of a 5th or 6th grader. Id. This is

consistent with someone being mildly or borderline mentally retarded.

School records indicate that for the most part Ernest remained in

classes for the Educable Mentally Retarded, at various schools

attended, until he stopped going to school at age 18. After

receiving all F’s both semesters of 10th grade and all F’s during a

partial stint in the 11th grade (at John Jay High School in

Cleveland), Ernest dropped out. It defies reason that Ernest was

even passed onto the 11th grade after he obtained all F’s both

semesters in the 10th grade. As one family member has stated, it

seemed that schools occasionally passed Ernest onto the next grade

level because they did not know what else to do.

Further indication that Ernest suffers from some form of mental

retardation is that his family has a history of learning and

developmental disabilities. Ernest’s sister, Debbie Reese Martin,

was placed in Learning Disabled classes beginning at the age of 6

and suffers from depression. Her son (Ernest’s nephew) Curtis Martin,

was also in Learning Disabled classes. Ernest’s sister, Rita Martin,

was in Learning Disabled classes and also suffers from depression.

Rita’s son, Donyelle Martin, is also in Learning Disabled classes,

and receives SSI for his disabilities. Ernest also has two children

of his own that suffer from developmental disabilities. Ernest’s

son, Darnell Reese, was placed in Learning Disabled classes and was

in school as Severely Behaviorally Handicapped. Ernest’s other son,

Timothy Martin, was likewise placed in pursuant to the United States

Supreme Court authority of Atkins v. Virginia. A copy of these

pleadings are attached hereto as Appendix exhibit 36.

Learning Disabled classes and has a history of behavioral

problems. Ernest also has one grandnephew, Kendrail Davis, who is in

mentally retarded/developmentally disabled classes and another

grandnephew, Kenneth Davis, who is placed in Special Classes. See

Appendix, exhibit 2. The individual history of Ernest Martin as well

as his family history strongly indicate that he has suffered

throughout his life from mild mental retardation or a disability

closely bordering mental retardation. In addition, he suffers from

some degree of mental illness, most likely an illness that borders

on an Axis 1 diagnosis. Under these circumstances, and in the

interests of justice and standards of decency, the execution of

Ernest Martin should not be countenanced. This Board should

recommend clemency for Ernest Martin and his sentence should be

commuted to a life sentence.

B. Offense

i) Plan was to rob, premeditation for murder lacking

The shooting

death of Robert Robinson, as is the case with any murder, was a

horrible and tragic crime. His death certainly caused great grief to

his spouse, Anna Robinson, as well as any other surviving family

members. The offense, however, does not fall into the category of

what is typically considered to be the most heinous and

reprehensible of crimes. This is partly because the shooting of Mr.

Robinson by all appearances was not preplanned.

According to the

state’s own witness, Josephine Pedro, in both her signed statement

to the police and in her testimony at trial, the only plan discussed

was that of robbing the store. There is no suggestion in the record

that there was any plan but that of robbery. The shooting, as

indicated by the state’s evidence presented, was apparently a knee-jerk

reaction to the sudden discovery by the perpetrator that the door

had been re-locked.

The record shows that this was troubling to the jury. As the

trial transcript reveals, during deliberations, which continued over

two nights and three days, the jury interrupted the process and

sought further clarification, by way of instructions from the trial

court. The jury requested further clarification regarding the legal

meaning of each of the following terms: “purposely,” “specific

intent,” and “prior calculation and design.” See Appendix, exhibit

3. These substantial questions surrounding whether the perpetrator

even truly intended to kill the victim raise a red flag as to

whether this offense merits imposition of capital punishment.

ii) Victim was shot at night through a door

Further evidence that

the perpetrator in this case did not actually intend to kill the

victim is the fact that the shots were fired at nighttime, through a

partially solid, partially glass door. Poor visibility could have

been a factor in the offense. The trial record is devoid of any

discussion regarding visibility through the door that night. However,

photographs of the scene are available. See Appendix, exhibit 4. The

photographs suggest that visibility through the door may well have

been obscured. The photographs raise substantial questions regarding

the intent of the gunman.

III. Ernest Martin’s Death Sentence Constitutes Unequal Justice,

Particularly Considering His Accomplice Received No Punishment

Whatsoever

1) Accomplice/state witness Josephine Pedro got off “scot-free”

while Ernest Martin received the death penalty

Facts of the offense

Ernest Martin’s death sentence resulted from a June 1983 aggravated

murder conviction in the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas for

the shooting death of Robert Robinson. During the early morning

hours of January 21, 1983, Josephine Pedro entered a small, cut-rate

drug store owned by Mr. Robinson on Fairhill Road in Cleveland,

Ohio.

As Mr. Robinson, age 70, finished locking the door behind Ms.

Pedro, two shots were fired through the glass portion of the door.

One of the shots struck Mr. Robinson in the chest, ultimately

causing his death. The only other individual in the store at the

time of the shooting was employee Monty Parker. Mr. Parker was in

the back of the store (in the wine room) from where he heard shots

fired but did not witness the shooting.

There were no witnesses to the actual shooting. There was one

witness, however, E.J. Rieves-Bey, who lived across the street from

Mr. Robinson’s store and who looked out his window after hearing the

shots fired and observed a man running away from the scene. A few

minutes after the shooting, Ernest Martin arrived at the store, as

did witness E.J. Rieves-Bey. Both Ernest and Mr. Rieves-Bey talked

to the police officers who arrived at the scene. The police also

talked to Monty Parker, and Josephine Pedro.

On January 26, 1983, Antoinette Henderson gave a statement to the

police in which she claimed that during the previous month of

December 1982 she had overheard Ms. Pedro and Ernest Martin

discussing a possible robbery of Mr. Robinson. Ms. Henderson, as it

turns out, was an acquaintance of Ms. Pedro and Ernest Martin and

had lived with them up until shortly before the subject offense.

Prior to the January 21, 1983 shooting of Mr. Robinson, Ms.

Henderson had a falling out with Ernest Martin and Ms. Pedro and was

forced to move out of their residence.

On January 29, 1983, eight days after the shooting, the police

entered the residence of Ernest Martin and Josephine Pedro and,

apparently without a warrant, arrested them both. On January 31,

1983, after approximately 72 hours in custody, Ms. Pedro gave a

statement to the police in which she incriminated herself, but also

identified Ernest Martin as the gunman in the shooting death of Mr.

Robinson.

At trial, physical or forensic evidence was lacking. There was no

physical evidence retrieved from the scene directly linking Ernest

to the crime. No murder weapon was ever produced by the state. Nor

was any physical evidence of a robbery produced by the state. Store

employee Monty Parker testified that he was aware of no money having

been taken from the store. The prosecution’s chief evidence against

Ernest Martin was the testimony of accomplice Josephine Pedro.

Ms.

Pedro testified about the plan to rob Mr. Robinson’s store. The plan

was for Ms. Pedro to get Mr. Robinson to open the door to the store

-- which he was known to keep locked during late hours -- under the

pretense that she needed to purchase some Nyquil for a cough. Ernest

was then to come into the store behind her and rob Mr. Robinson.

Based on Ms. Pedro’s testimony, Ernest was not only found guilty but

received the ultimate sanction – death by execution. Yet Ms. Pedro

was never prosecuted and received no punishment whatsoever.

This grossly disparate outcome constitutes disproportionate

punishment. On this basis, Ernest Martin’s death sentence should be

commuted.

2) Ernest Martin has already spent 20 years in prison for this

offense

As of this summer, Ernest Martin will have been imprisoned on Ohio’s

death row for 20 years. Due to the unique status of capital-sentenced

inmates, conditions on death row are very restrictive. For example,

inmates on death row have access to very little programming compared

to the inmates in the general prison population. Twenty years of

death row confinement, awaiting execution, is a long time and is

severe punishment in and of itself. Given the circumstances of this

offense, particularly the uncertainty regarding the intent of the

shooter, Ernest Martin has already received considerable punishment.

Recently in Knight v. Florida, United States Supreme Court

Justice Breyer discussed the impact of a lengthy delay upon an

individual awaiting execution: It is difficult to deny the suffering

inherent in a prolonged wait for execution--a matter which courts

and individual judges have long recognized. [Citation omitted] More

than a century ago, this Court described as "horrible" the "feelings"

that accompany uncertainty about whether, or when, the execution

will take place.

* * *

At the same time, the longer the delay, the weaker the

justification for imposing the death penalty in terms of

punishment's basic retributive or deterrent purposes. [Citation

omitted] Nor can one justify lengthy delays by reference to

constitutional tradition, for our Constitution was written at a time

when delay between sentencing and execution could be measured in

days or weeks, not decades.6

The concerns expressed by Justice Breyer are applicable here.

Furthermore, Ernest Martin’s length of confinement is now twenty

years greater than that of accomplice Josephine Pedro. This

disparate treatment is unconscionable. Ernest Martin should be

granted clemency and his sentence should be commuted.

IV. Ernest Martin’s Death Sentence Resulted From An Unfair And

Unreliable Process

Ernest Martin’s death sentence was a consequence

of a flawed and unfair trial process. The results of his trial,

regarding both his actual guilt of the offense and his deserving of

a death sentence, are suspect and unreliable.

1. Ohio’s death penalty law was new in 1983

Ernest Martin’s capital trial in June 1983 was one of the earliest

to go to trial under Ohio’s newly enacted death penalty statute that

became effective in October of 1981. Thus, none of the parties

involved in Ernest Martin’s trial could possibly have been

experienced with capital proceedings under Ohio’s new death penalty

statutory scheme. Defense counsel, for example, undoubtedly had no

experience in presenting a case in mitigation (at the sentencing

phase) under the new procedures and new legal standards. Nor would

counsel have had any other sources from which to obtain experienced

guidance. It is readily apparent from the record of the trial that,

as a consequence of this lack of experience under the new death

penalty provisions, Ernest Martin suffered severely. In the end,

Ernest Martin was sentenced to death under circumstances that fall

short of the exacting level of confidence necessary to carry out his

execution.

2. The inexperience of the trial court led to shoddy, unreliable

proceedings.

The 1983 trial record reveals a number of irregularities occurring

during the proceedings and calls forth a host of questions and

suspicions regarding the outcome of Ernest Martin’s trial. In all

likelihood the court’s, and counsel’s, unfamiliarity with a new

process contributed to these irregularities. Regardless of the

cause, however, the result was an unfair process for Ernest Martin.

Perhaps the most notable irregularity in this case is the lack of

a complete record of trial proceedings. Significant portions of the

proceedings are missing. Despite it being a capital case, the trial

court, as well as defense counsel and the prosecutors, failed to

ensure that a thorough record was preserved. First, none of the pre-trial

proceedings held in court were recorded. Second, the proceedings are

replete with side-bars (discussions between court and counsel at the

bench) that were not recorded. Third, at both the culpability phase

and the mitigation (sentencing) phase, the proceedings occurring

when the jury returned from deliberations and returned its verdict,

(which should include individual polling of the jury), were not

recorded. Fourth, it has always been suspected, though counsel for

Ernest Martin has never been able to prove, that immediately

following the jury being sent into deliberations at the culpability

phase, there were proceedings before the court regarding witness E.J.

Rieves-Bey, who was a critical witness for the defense but never

testified because he showed up minutes late for trial. Lastly, the

record of the proceedings occurring in September and October of 1983

regarding a defense motion for new trial is also irregular. The

transcript of that record ends with a notation that the hearing was

continued until a further date. No further record exists.

The trial court engaged in improper behavior by over-reaching and

taking on the role of an advocate in the case. For instance, prior

to the mitigation hearing the trial judge took over the role of

counsel – seemingly for the defense but actually in favor of the

prosecution. As the parties approached the mitigation hearing, the

record reveals that the trial judge, on his own initiative,

undertook investigative action to obtain Ernest Martin’s psychiatric

records. Astonishingly, the trial judge had the records sent

directly to the court and not to defense counsel. Without objection

by defense counsel, the trial judge reviewed the documents and

stated on the record his interpretation of them regarding their lack

of value as evidence for the defense.7 See Appendix, exhibit 5.

At the mitigation hearing the trial judge again took over the

role of defense counsel – again to the detriment of Ernest Martin –

when the judge began calling out into the audience seated in the

courtroom looking for volunteers to come to the witness stand to

testify on Ernest Martin’s behalf. See Appendix, exhibit 6. This

stunning departure from proper procedures prejudiced Ernest in that

it created the impression that Ernest’s own family members had

nothing good to say about him.

3. The inexperience of defense counsel led to poor representation.

7 The Cuyahoga County trial judge in this case, Daniel O.

Corrigan, does not have a stellar record. In 1976 Judge Corrigan was

reprimanded by the Cleveland and Cuyahoga County Bar Associations

for failing to conform his conduct to the precepts of the Judicial

Canons of Ethics and the Judicial Code of Conduct. This stemmed from

findings that Judge Corrigan, who was known to be heavily in debt at

the time, had been involved in business transactions with attorneys

who appeared before him or received appointments by him. See

Appendix, exhibit 7.

Years later, in 1988, Judge Corrigan was sued

by a Cleveland defense attorney who claimed that the Judge appointed

attorneys to cases dependent upon their contributions to his

election campaign, averring that the Judge “trade[d] cases for

cash.” State of Ohio, ex rel. Kirtz v. Corrigan, 1990 WL 7158 (Ohio

App. 8Dist).

Ernest Martin received minimal assistance at both phases of his

trial from courtappointed counsel. This minimal assistance

contributed to his receiving an overall unfair trial. Counsel

inexplicably allowed the case to be rushed to trial. Ernest was

indicted on February 9, 1983, and defense counsel James Carnes and

Herbert Adrine were assigned to the case on March 2, 1983. The trial

began on June 6, 1983. The record suggests that counsel was hoping

for a plea agreement and did not expect to go to trial. That

translated into an utter failure to prepare their case for trial.

Defense counsel’s poor performance began with their numerous

failures in the pretrial preparation. Defense counsel filed a total

of three (3) pre-trial motions: a motion for discovery, a motion for

an investigator, and a motion to sever offenses. Such a paucity of

pretrial defense motions is unheard of in a capital case. Counsel

failed to file the most obvious of pretrial motions – a request for

a bill of particulars, a motion to suppress evidence based on a

warrantless arrest, a motion for funds for an expert in ballistics -

let alone the host of other motions which are filed by defense

counsel in a capital case as a matter of course to at least preserve

issues for appeal.

Defense counsel’s failure to file any challenges

to the constitutionality of what was then Ohio’s new death penalty

law exposes their cavalier approach to Ernest’s case. Even though

Ohio’s statute has withstood challenges over the years, back then

failing to fulfill their rudimentary duty to challenge a new statute

for a capital client reveals their across-the-board ineffectiveness.

Furthermore, defense counsel failed to adequately investigate the

facts of the case. Most importantly, counsel failed to personally

meet with and interview witness E.J. Rieves-Bey. Mr. Rieves-Bey was

an important witness because he was the only witness who observed

the gunman running away from Mr. Robinson’s store after the shots

were fired. Counsel did obtain a statement from Mr. Rieves-Bey taken

by a court-appointed investigator well before trial. The statement

was certainly helpful to the defense in that Rieves-Bey was able to

say that: 1) “I think they got the wrong man.”; 2) the man he saw

running from the store was bigger than Ernest Martin; and 3)

Antoinette Henderson (Rieves-Bey’s sister-in-law who testified about

the planning of the robbery), was “a big liar” who was feuding with

Josephine Pedro and holding a grudge against both Ms. Pedro and Mr.

Martin.

Defense counsel failed to seize upon the usefulness of this

witness in conducting their defense. Based on his above statements

alone, defense counsel should have, at a minimum, met with E.J.

Rieves-Bey, prepared him for testifying, and subpoenaed or otherwise

secured his presence for trial. Defense counsel also should have

conducted interviews of Antoinette Henderson, E.J. Rieves-Bey’s

brother (common-law husband of Ms. Henderson), and Ms. Pedro based

on Mr. Rieves-Bey’s statement regarding Ms. Henderson’s motives for

lying to the police. Defense counsel did none of this, and instead

incredibly relied upon prosecutor Carmen Marino to subpoena Mr.

Rieves-Bey to appear. For some reason Mr. Rieves-Bey did not timely

make it to court.8

8 The record of the prosecutor, Carmen Marino, like that of Judge

Corrigan, is not untarnished.

Prosecutor Marino has a proven track

record of violating constitutional rules of fair play at trial.

State v. Liberatore, 69 Ohio St.2d 583, 589-90 (1982) (“the

prosecutorial blunders in this case are too extensive to be excused.”);

State v. Owensby, 1985 Ohio App. LEXIS 7351, *3 (1985) (“prosecutor’s

comments clearly outside the bounds of mere ‘earnestness and

vigor[.]’”); State v. Heinish, 1988 Ohio App. LEXIS 3644, *20 (1988)

(“Clearly the prosecutor improperly commented on excluded evidence.”);

State v. Lott, 51 Ohio St. 3d 160 (1990); State v. Harris, 1990 Ohio

App. LEXIS 5451 (1990) (prosecutorial misconduct found, but harmless);

State v. Hedrick, 1990 Ohio App. LEXIS 5647 (1990) (prosecutorial

misconduct by making improper comments on matters outside of record

and on defendant's failure to testify.); State v. Durr, 58 Ohio St.3d

86 (1991) (improper comments on the appellant's unsworn statement,

the appellant's prior convictions, and mitigating factors held

harmless.); State v. Keenan, 66 Ohio St.3d 402 (1993) (presenting an

“aggravated example” of prosecutorial misconduct); State v.

D’Ambrosio, 67 Ohio St.3d 185 (1993) (prosecutorial misconduct found,

but either waived or harmless); State v. Johnson, 1992 Ohio App.

LEXIS 4256, *17 (1993) (prosecutorial misconduct “[rose] to the

level of being constitutional errors.”); State v. Matthews, 1999

Ohio App. LEXIS 896, *5 (1999) (prosecutor denied making a deal with

witnesses, however “[t]here is ample evidence to suggest that [the

witness] at least did in fact receive just what the assistant county

prosecutor said he would not give him.”).

Defense counsel’s failure to ensure the presence of E.J.

Rieves-Bey was inexcusable. He was the lone witness the defense

planned to present, as evidenced by counsel’s reference to Mr.

Rieves-Bey during opening argument. See Appendix, exhibit 8. His

testimony was highly important. Though the state has argued that

Rieves-Bey’s statements were in some ways consistent with the story

of Josephine Pedro, Mr. Rieves-Bey has always maintained that the

man he saw running away from the store after the shots were fired

was not Ernest Martin.

After Mr. Rieves-Bey failed to appear,

counsel had nothing whatsoever to present in defense. Indeed, the

defense rested without putting on any witnesses or evidence of any

kind. At Ernest Martin’s sentencing hearing, defense counsel

exhibited a complete lack of experience and understanding as to how

to present a case in mitigation. Counsel’s performance at mitigation

was nothing short of abysmal.

Defense counsel wholly failed to prepare for the mitigation

hearing. Remarkably, defense counsel failed to do even the most

obvious preparation by neglecting to conduct an investigation into

Ernest’s background. In order to properly prepare and present

evidence in mitigation, it is necessary to investigate and assess

the client’s life history, including psychosocial and physical

development. Mitigation investigation requires thorough interviewing

and record collection, with the interviewing typically beginning

with the client’s immediate family, and extending to significant

others such as teachers, mentors, local pastors, and additional

relatives and acquaintances.

Here, except for reportedly limited and frustrating contacts with

the father, counsel failed to even meet with and/or interview

Ernest’s immediate family. These family members included Ernest’s

mother, three brothers, three sisters, and grandmother – all of whom

were willing to assist Mr. Martin in any way they could. See

Appendix, exhibits 9-16.

Counsel also failed to conduct a collection of records and

documentary evidence pertinent to their client and his history. The

most obvious documents counsel failed to pursue were Ernest’s

medical, mental health, educational, employment, juvenile and adult

prison records. Counsel further failed to seek the services of an

expert to pursue possible medical, psychological, sociological or

other explanations for the offense for which their client was being

sentenced.

Given counsel’s lack of preparation, it is not surprising that

the mitigation hearing was nothing short of disastrous. First,

defense counsel waived opening argument. This failure is inexcusable

in a capital case and indicates a complete lack of a defense theme

or strategy. Second, defense counsel called only two witnesses: 1) a

probation officer; and 2) Ernest’s mother.

The probation officer testified for 2-3 minutes in order to place

a probation report into evidence which did more harm than good. The

report brought in evidence of Ernest’s juvenile record and a victim

impact statement which, but for counsel’s grave error, never should

have gone to the jury. Ernest’s mother, the only witness of the two

called by defense counsel who could do any good for the client, was

unprepared.

While counsel did ask her to write a statement

concerning her son, Mrs. Martin was not informed until the day of

the mitigation hearing that she would be asked to testify. See

Appendix, exhibit 9. Nor had counsel contacted Mrs. Martin before

the mitigation hearing to confirm or discuss any information that

she had provided in her written statement regarding her son’s

background. Of course, trial counsel should have begun discussing

Mrs. Martin’s testimony with her months before when they should have

interviewed her as a fact witness for trial, let alone at some point

before the mitigation hearing. This deficient performance by counsel

was wholly ineffective and constituted an abdication of advocacy on

behalf of the client.

The mitigation hearing deteriorated following Mrs. Martin’s

testimony. At that point defense counsel declared to the court that

they had nothing further to offer. Yet the hearing continued. The

trial judge, perhaps due to perceived inadequacies of counsel,

proceeded to assume counsel’s role. Remarkably, the trial judge

began calling out to the audience seated in the courtroom looking

for volunteers to come to the witness stand to testify on Ernest

Martin’s behalf. Defense counsel allowed this circus-like atmosphere

to flourish without objection.

The trial court’s conduct created the

prejudicial and incorrect appearance that not even Ernest Martin’s

closest family members desired to say anything positive on his

behalf. See Appendix, exhibit 6. Many of Ernest’s family members

could have testified at his mitigation hearing, but they were never

interviewed, let alone prepared, by defense counsel. See Appendix,

exhibits 9-16. Ernest’s grandmother was then “put on the spot” by

the trial court and decided on the spur of the moment to testify.

Her unprepared testimony, which constituted all of five pages of

transcript, concluded the pathetic defense in mitigation.

In sum, Ernest Martin’s court-appointed counsel performed poorly

at all phases of his trial. Their failures were pervasive. Their

poor performance certainly contributed to the overall unfairness of

Ernest Martin’s trial and to the undue harsh result Ernest incurred.

4. The resulting verdict and death sentence are unreliable

The trial of Ernest Martin was unfair. The trial was unfair because:

the trial court and counsel were unfamiliar with trying a capital

case under the new death penalty statute; important portions of the

trial record were not kept or are otherwise missing; important

pieces of physical evidence were destroyed and no longer exist; the

trial court engaged in over-reaching and improper conduct; the

prosecution relied not on physical or forensic evidence but on the

testimony of suspect witnesses; defense counsel inexplicably failed

to subpoena the presence of the lone planned defense witness, under

suspicious circumstances wherein defense counsel relied on a

subpoena issued by the prosecuting attorney; and defense counsel

practically abandoned their client after he insisted on his

innocence and demanded a trial, failing to present any defense at

the culpability phase and allowing the mitigation phase to collapse

before the court and jury.

Lingering doubts about guilt

Due, in part, to this unfairness, there continue to be lingering

doubts regarding Ernest’s guilt. The prosecution’s case relied upon

suspect witnesses, not physical evidence. Virtually no physical or

forensic evidence was produced at trial proving Ernest Martin shot

Mr. Robinson. No gun that could be linked to the shooting was ever

produced. No items of evidence such as clothing taken from Ernest

Martin on which the victim’s blood, or pieces of glass from the door,

was found to connect him to the crime. Nor was there any evidence of

gunshot residue, from paraffin tests, found on Ernest Martin or his

clothing.

The state’s witnesses, upon whose testimony the state largely

rested its case, were untrustworthy and unreliable. Witness

Josephine Pedro was an alleged accomplice to the murder. Although

she testified that she was not provided any promises in exchange for

her testimony against Ernest Martin, she very curiously was never

prosecuted, nor apparently charged, with any offense related to the

murder. See Appendix, exhibit 17. Given what Ms. Pedro had to gain,

i.e. her freedom from lengthy incarceration, by satisfying the

state’s desire that she testify against Ernest Martin, her testimony

is highly suspect.

Witness Antoinette Henderson, who could only say

that she overheard a conversation between Ernest and Ms. Pedro in

which they purportedly discussed the possibility of robbing Mr.

Robinson, was also unreliable. Ms. Henderson had formerly resided

with both Ms. Pedro and Ernest, and reportedly had had a falling out

with the two of them that caused her to have to move out of the

residence. See Appendix, exhibit 18, at pp. 7-8. Further, Ms.

Henderson was plainly shown to be untrustworthy while on the witness

stand. During cross-examination, for example, defense counsel caught

her in a bald-faced lie, under oath, regarding the number of

children to whom she had given birth. See Appendix, exhibit 19.

Furthermore, according to the statement provided by E.J. Rieves-Bey,

Ms. Henderson was known to “lie about everything.” See Appendix,

exhibit 18, at p. 5. The testimony of Ms. Henderson, like that of

Josephine Pedro’s, merits little consideration.

In addition, evidence was weak to prove the “specific intent” to

kill necessary for Ernest’s conviction. The very circumstances of

the crime call this element of the offense into question. The

evidence presented was that Mr. Robinson was shot through a glass

door, late at night, while Mr. Robinson was standing inside his

store and the perpetrator was outside. No evidence was presented by

the State to demonstrate the extent of visibility, if any, into the

store that the perpetrator would have or could have possessed. None

of the witnesses testified as to how much of the door was composed

of glass, as opposed to how much of it was solid wood or other

material.

Moreover, Ms. Pedro’s statement to the police confirms that, if

her story is to believed, there was never any intention to kill Mr.

Robinson; rather, the intention was only to rob him: “T.J. [Ernest]

told me that all he was going to do was pull the gun and Robb [sic]

the old Man and get the money and split.”9 Under these circumstances,

and in light of the lack of evidence presented by the state on this

issue, a myriad of scenarios can be conceived consistent with the

evidence presented in which the perpetrator of the offense fired the

gun without possessing the requisite specific intent to kill someone.10

In cases of circumstantial evidence, as is the case here, the jury

should be able to rule out other possible scenarios that are

consistent with the evidence presented. Here, however, the evidence

was insufficient to rule out other possible scenarios in which the

requisite specific intent to kill was absent.

The question of “specific intent” was of sufficient import that

it was clearly a concern to Ernest’s jury. Indeed, during their

deliberations at the culpability phase, the jury forwarded a written

note to the trial judge requesting clarification of their

instructions on this issue. See Appendix, exhibit 20. In sum, the

state’s case relied on weak, circumstantial evidence. The evidence

produced posits a theory of a crime based upon speculation and the

testimony of unreliable witnesses. As a consequence there continue

to be lingering doubts regarding Ernest Martin’s guilt. Under such

circumstances, his death sentence should be commuted.

Death sentence an unreliable result

The unfairness and irregularities of Ernest’s mitigation hearing

likewise undermine confidence in the accuracy, and appropriateness,

of his sentence of death. Ernest might not be on death row today

were it not for the miserable performance of his defense counsel.

Counsel helped ensure a death verdict by failing to present anything

of mitigating value. Had counsel fulfilled their duty to conduct a

background investigation of their client, and had counsel presented

available mitigating evidence, e.g., regarding both Ernest’s

psychological dysfunction and problems in the area of mental

retardation, the jury may have been swayed to impose a different

sentence.

9 January 31, 1983 Police Statement of Josephine Pedro. 10 As examples of such possible scenarios, the perpetrator may have simply

panicked when he encountered the locked door to the store, and began

firing his gun without particularly aiming at anything or thinking

precisely about where he was shooting; or the perpetrator may have

encountered the locked door and intended only to shoot through the

door to gain entrance into the store, not intending to hit anyone

with the gunshots. 11 The other recognized purpose for vesting the

power of clemency in the executive was that it permitted the

president to pursue ends beneficial to the state such as the

quelling of rebellions or the protection of spies.

Ernest’s death sentence is further unreliable because the record

of the jury returning their recommendation of a death sentence is

missing. When the jury returns its verdict, each jury member is

typically “polled” to confirm that the verdict truly reflects his or

her individual decision. Without any record of this, there is, and

will always be, an uncertainty regarding the death verdict

delivered.

V. Role of Clemency

The role of clemency, in short, is to correct manifest injustice and

to temper harsh and disproportionate court rulings with the

Executive’s power of mercy. The discretion to grant clemency is

broad.

The power of clemency is vested in the governor of Ohio by

Article III, Section 11, of the Ohio Constitution. The governor is

given broad discretion in exercising that power. Section 11 empowers

the governor to grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons for all

crimes and offenses (except in cases of treason and impeachment),

“upon such conditions as he may think proper.”

While there is little

known legislative history behind this provision of the Ohio

Constitution, it is considered probable that the power was given to

the governor for reasons similar to those that led to the vesting of

the federal clemency power in the president. One of the two distinct

purposes behind the authorization of the presidential power of

clemency was that it acted as a check on the legislative and

judicial branches by permitting the president to rectify injustices

that might result from inflexible adherence to the law.11

In Ohio, applications for pardon or commutation of sentence are

to be made to the Ohio Adult Parole Authority (APA), which

subsequently issues a report and recommendation to the governor.12

The little guidance provided by way of statutory or administrative

standards as to when clemency should be recommended by the APA is

broad in scope, and speaks to the interests of justice.

Specifically, the guidance given is that the APA may recommend

clemency if it reasonably concludes that such action “would further

the interests of justice and be consistent with the welfare and

security of society.”13

The United States Supreme Court has also clarified the role of

clemency. In Ex parte Grossman, addressing the role of the pardoning

power in the federal constitutional scheme, the Supreme Court stated:

Executive clemency exists to afford relief from undue harshness or

evident mistake in the operation or enforcement of the criminal law.

The administration of justice by the courts is not necessarily

always wise or certainly considerate of circumstances which may

properly mitigate guilt. To afford a remedy, it has always been

thought essential … to vest some other authority than the court’s

power to ameliorate or avoid particular criminal judgments.14

The Supreme Court emphasized the importance of discretion in the

exercise of the clemency power, stating that “whoever is to make it

useful must have full discretion to exercise it.”15 More recently,

in Herrera v. Collins, the Supreme Court described the power of

executive clemency as the “fail-safe” in the American criminal

justice system, recognizing that “[i]t is an unalterable fact that

our judicial system, like the human beings who administer it, is

fallible.”16

The role of clemency has taken on greater significance

in recent years due to state and federal legislation restricting an

inmate’s access to state post-conviction and federal habeas corpus

relief. Changes in both state law in Ohio and federal law in 1996

make it exceedingly more difficult for an inmate to bring forth any

subsequent petitions for judicial relief beyond his “one bite at the

apple” in state and federal post-conviction proceedings. It is a

virtual mathematic certainty that such restrictions will result in

fewer injustices in capital cases being rectified by the courts. For

this reason, the broad power to grant clemency should be exercised

more frequently to serve as the safety net for those injustices the

courts fail to address.17

VI. The Totality of Circumstances Warrant Clemency

The totality of the circumstances presented herein warrant the

granting of clemency to Ernest Martin. As demonstrated, there are a

number of injustices extant in Ernest’s case. If not in their

individual capacity, then considered as a whole, these injustices

demand relief. The numerous injustices incurred by Ernest relate to,

and exacerbate, one another. The injustice of Ernest receiving death

for an offense not among the “worst of the worst” relates to the

injustice of accomplice Josephine Pedro getting off “scot-free.” If

the offense had truly been so appalling and heinous, it is unlikely

that the prosecution would have allowed an accomplice to go

completely free.

The injustice of Ernest receiving death despite his serious

mental disabilities also relates to the injustice resulting from Ms.

Pedro’s freedom, in that Ernest’s mental deficits make it likely

that Ms. Pedro, more so than Ernest, was responsible for plotting

the robbery. Lastly, the injustice of the disproportionate

punishment and the extremely disparate result between Ernest Martin

and Josephine Pedro is inter-related with the injustice of the

unfair trial process.

The combination of the lack of experience of

the parties regarding the newly enacted death penalty laws and

procedures, the irregularities that occurred (including defense

counsel relying on a prosecutor to subpoena a defense witness), the

inappropriate conduct of the trial judge, the intellectual deficits

of the client, and the abysmal performance by court-appointed

defense counsel, explains how such a manifest injustice could occur.

VII. Clemency Request

Ernest Martin, through counsel, in the interests of justice and

mercy, pleads for clemency and asks for a commutation of his death

sentence to a life sentence.

Respectfully submitted,

DAVID H. BODIKER, Ohio Public Defender

TIMOTHY R. PAYNE, Assistant State Public Defender KYLE E. TIMKEN,

Assistant State Public Defender Counsel For Petitioner ERNEST MARTIN

APPENDIX OF SUPPORTING DOCUMENTS

Exhibit 1 2002 Gallup Poll regarding death penalty and mental

retardation Exhibit 2 February 21, 2003 Affidavit of Mitigation

Specialist Pam Swanson Exhibit 3 Trial transcript, pp. 644 Exhibit 4

Photos of crime scene - store door Exhibit 5 Trial transcript, pp.

651-54, 688 Exhibit 6 Trial transcript, pp. 690-91 Exhibit 7 March

3, 1976 news article – Judge Daniel O. Corrigan Exhibit 8 Trial

transcript, p. 43 Exhibit 9 July 13, 1987 Affidavit of Frances

Martin Exhibit 10 July 13, 1987 Affidavit of Terry Davis Exhibit 11

July 13, 1987 Affidavit of Lee Martin, Jr. Exhibit 12 July 13, 1987

Affidavit of Eric Martin Exhibit 13 July 13, 1987 Affidavit of Erwin

Martin Exhibit 14 July 13, 1987 Affidavit of Debra Reese. Exhibit 15

July 13, 1987 Affidavit of Rita Martin Exhibit 16 Trial transcript,

pp. 314-15 Exhibit 17 March 28, 1983 statement of E.J. Rieves-Bey

Exhibit 18 Trial transcript, pp. 358-59 Exhibit 19 Trial transcript,

pp. 644-50 Exhibit 20 Letter from Debrah Reese Martin (Ernest’s

sister) Exhibit 21 Letter from Erwin Martin (Ernest’s brother) 28

Exhibit 22 Letter from Curtis Martin (Ernest’s nephew) Exhibit 23

Letter from Germaine Grayson (friend of family) Exhibit 24 Letter

from Frances Martin (Ernest’s mother) Exhibit 25 Letter from Hattie

Johnson (Ernest’s grandmother) Exhibit 26 Letter from Rita Martin (Ernest’s

sister) Exhibit 27 Letter from Laketta Tate (Ernest’s daughter)

Exhibit 28 Letter from Kathryn Davis (Ernest’s niece) Exhibit 29

Letter from Terry L. Davis (Ernest’s sister) Exhibit 30 Letter from

Shelley Reese (mother of Ernest’s child) Exhibit 31 Letter of

Valerie Tate (mother of Ernest’s two children) Exhibit 32 Letter

from Beverly A. Keyes (friend of family) Exhibit 33 Letter from Rosa

Lee (friend of family) Exhibit 34 Letter from Vanessa Tate (aunt of

Ernest’s two children) Exhibit 35 Letter from Reverend Robert Hull (friend

of family) Exhibit 36 February 24, 2003 Motion for Stay and Petition

to Vacate Judgment based on mental retardation (Cuyahoga County

Court of Common Pleas) |