Three months later, he was formally charged with the August 21, 1970, slaying of Virginia Maines, a 20-year-old housewife in Gaston, North Carolina. On June 5, he was indicted for the August 10, 1970, murder of James Sires, a service station operator in Beaufort County, South Carolina.

According to authorities, the drifter's seven other victims were dispatched in separate incidents in June and December 1970, and in January 1971.

Outrage:

The Peg Cuttino story

By Seamus McGraw

A Child in the Woods

He could feel them looking at him. The chief of the

State Law Enforcement Division, the local police chief, the coroner, all

three of them: Their mute gaze hung on him like burrs on a horse blanket.

He tried not to show it, but Sheriff Byrd Parnell could feel their eyes

boring into the back of his head. He knew they were studying him. They

were looking to him for some signal, some clue as to how they should

react to the gruesome sight on the forest floor before them.

It wasn't that they had never seen a murder scene

before. All of them were professionals, with the possible exception of

the coroner, Howard J. Parnell, a nondescript and slightly funereal man,

who, by accident of adoption, was also the sheriff's nephew. By virtue

of fate, it seemed, he was a mortician. And by dint of politics, he was

the coroner, charged with the usually mundane responsibility of

attaching causes to unobserved deaths. The others, though, were all men

who had spent their lives in the sometimes politically charged world of

small-time South Carolina police

work. They were no strangers to the bloody detritus of mayhem, though

most often, that violence was committed by men with guns against men

with guns and, as often as not, it was fueled by booze. But this was

different.

It wasn't just that the victim was so young, though

certainly she was. Just 13 at her last birthday, she had seemed to exude

a kind of fawn-like innocence. It was a treasured trait in the

conservative communities of rural

South Carolina, particularly back

then, in 1970, when

Vietnam and

Kent

State were still a world away and

before Watergate had truly destroyed the notion of innocence. She was

practically wearing a uniform of innocence when they found her; the prim

blue blouse, the modest white skirt, the girlish, polka-dot sash.

But it wasn't just the tragedy of betrayed innocence

that made this case different. It wasn't the fact that she had been so

brutally slain, or even that the modest white skirt was hiked up around

her hips, and that, by all appearances, she had been raped and sodomized.

Even then, and even in this close-knit corner of the South, where

everyone, it seemed, had been washed in the blood of the lamb, such

savagery was hardly unheard of.

What made this case different was who the victim was.

Or, to put it more accurately, what she was likely to become. In life,

Margaret "Peg" Cuttino had been the oldest daughter of a prominent man,

a state legislator, a powerful man by the standards of the time and

place who commanded respect and attention. That fact alone made her

death different than any others in

Sumter County,

and in all likelihood, Sheriff Byrd Parnell knew it that day as he stood

there in the woods staring down at the violated figure on the ground,

covered, just barely, with leaves and a few sticks. That fact alone made

it a case that could not be allowed to linger unsolved. That would have

been so even if Sheriff Parnell was not who he was: a veteran lawman,

president for a time of the National Sheriff's Association, and, by all

accounts, a hard-nosed cop who had always made it a maxim to leave no

crime unsolved before election time.

In time, Parnell would be able to declare the case

solved. The break in the case, such as it was, would come when William "Junior"

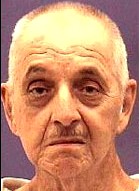

Pierce, a slow-witted convict from Georgia, a man with a long history of

arrests for both petty and violent crime, would allegedly confess to the

killing of Peg Cuttino, perhaps under duress, perhaps even under threat

of torture.

But what Sheriff Parnell and the others who stood

there could not possibly know was that the case, in some ways, would

never really be resolved. Even now, more than 30 years after Peg

Cuttino's murder, questions still dog the case. Three decades after the

case was supposedly closed it remains as controversial and divisive as

ever. After all these years, simply mentioning the names Junior Pierce

or Peg Cuttino in some quarters of Sumter County still pits neighbor

against neighbor.

There are some, many perhaps, in

Sumter County

who believe that authorities never really solved the case, and instead

insist that Junior Pierce, though hardly an innocent man, could not have

killed Peg Cuttino on the day and in the manner authorities have long

claimed. In the three decades that have passed since Peg Cuttino's death,

political careers including Sheriff Parnell's have been dashed on the

rocks, all as a result of the storm of controversy generated by the

case. A deep rift and a festering sense of mistrust have carved their

way through the sandy soil of

Sumter

County. It is a measure of how deep

and dark that chasm is that for time during the contentious debate over

the case, the word of a blood-thirsty convict, an admitted serial killer

named Pee Wee Gaskins, for a time carried as much weight with the people

of Sumter as their elected sheriff and others charged with protecting

the peace and safety of the community.

Even today, the case still pits what most observers

call "regular folks," hard-working and religious people who deeply

believe that Peg Cuttino's death was linked, however tenuously, to some

deep, dark secret in the woods outside

Sumter, a secret that somehow

involved powerful people.

In short, more than 30 years after Peg Cuttino's body

was found in a shallow, makeshift grave in the depths of

Manchester

State

Forest, more than 25 years after her

presumed killer was convicted of the crime, the case is still, in the

minds of many, a mystery.

A Death in Sumter

It looked as if Christmas was going to come gently to

Sumter County

that year, riding in on the back of a 65-degree breeze blowing in from

the coast. It was Dec. 18,

1970, a Friday, and in the small town of

Sumter, an army of young students

burst through schoolhouse doors for the first day of their Christmas

break.

Peg Cuttino was among them. A 13-year-old girl on the

verge of maturity, the 5-foot-2, 130-pound girl with shoulder-length

brown hair was a daughter of the local aristocracy. Her father, James

Cuttino, was then a member of the state legislature, and the family

lived in a pleasant, though hardly ostentatious, house at

45 Mason Croft Drive.

In many respects, the bright and athletic eighth-grader

was the picture of youthful gentility. Ever since she was a young child,

she had been a regular fixture at political events in the conservative

county, handing out fliers for her father's campaigns and chirping to

anyone within earshot in her girlish little voice: "Please, vote for

my daddy."

As she grew older, she became more active in church

groups. She sang in the youth choir at the First Presbyterian Church,

studied the Bible at Sunday school and was a member of the Pioneer Youth

Fellowship. She was a starter on the girl's varsity basketball team at

the Alice

Drive Junior High School,

a few blocks from her house.

She was, it seemed, a parents' dream. At least that's

how people described her, and her staunch traditionalism, it seemed, was

a comfort to her staunchly traditional neighbors in

Sumter. There were rumors, of course, as there

always are, that perhaps Peg Cuttino was not as perfect as she might

have appeared. She is said to have displayed flashes of rebellion, and

there were also stories that she might have stormed out of her parents'

house on at least one occasion. But even the gossips tended to depict

her behavior as typical teenage angst and nothing more, a minor flaw

when they contrasted Peg Cuttino's bearing and demeanor to the wild

antics and youthful rebellion that seemed to be taking hold all over the

country in the winter of 1970.

Little by little, those same trends were beginning to

appear in Sumter. Drugs were starting to appear. Though it would never

be confirmed, and in fact would be flatly rejected by most people in a

position of responsibility in the community, a legend had started to

take root in

Sumter, a legend about an old

abandoned trailer somewhere in the woods where some of the youth of

Sumter County

would gather for wild, drug-fueled parties. There was even talk, idle

talk it now seems, that young people had been plied with drugs and

forced to perform in grainy pornographic films which were later sold to

a distributor in

California. In a peculiarly

Southern Gothic twist on that legend, it was even whispered over back

fences and at church barbecues that the dastardly porno ring had snared

some of the children of well-connected people in town.

It didn't matter that no proof of such an operation

ever surfaced. All that really mattered was that the rumors resonated

deeply with some of the more traditional folks in

Sumter County

who were threatened by young people.

Against the backdrop of such fear, the public image

of Peg Cuttino, dressed for the last day of the fall semester in her

modest white skirt with the polka-dot sash, seemed positively angelic.

She had gotten out of school that day at about 11:30

a.m. and chatted briefly with her mother, saying she wanted to walk the

few blocks to the

Willow Drive

Elementary School to have lunch with

her younger sister, Pamela.

Her mother thought nothing of it. Authorities would

later say that the young girl walked briskly down Willow Drive and was

seen as she passed the YMCA building, then under construction on a

vacant lot alongside her sister's school. In what would someday become a

subject of great controversy in the case, among the men working on the

building was Pee Wee Gaskins. Then a small-time hood and part-time

police informant, Gaskins would later go on to become one of the

nation's most fearsome serial killers. Years later, Gaskins would play a

crucial role in the ongoing war over the Cuttino case. But on that day,

he was just another nobody on the street.

To this day, no one really knows what happened after

Peg Cuttino walked past the YMCA. She never made it the scant few yards

to her sister's school.

About two-and-a-half hours later, when Peg still had

not returned, her mother started to fret and telephoned police. It was

less a measure of her family's prominence and influence in the community

than an example of simple small-town values that within minutes, local

radio stations broadcast an alert for the missing girl. All the same,

her family may have been a factor when, within a few hours of those

first broadcasts, a massive search was launched.

There were some people who claimed to have seen her

on the street in the moments leading up to her disappearance. Among them

was a schoolmate. Though not a close friend of Peg's, the boy said he

knew her slightly and insisted that he had caught a glimpse of her at an

intersection several blocks from the school shortly before

1 p.m. and that she wasn't alone. According to published

reports at the time, the boy said he had seen Peg Cuttino in the back

seat of a car with two other people. "There was a man driving the car

with dark-colored hair with glasses," he told authorities, according to

a version of the events later recounted in print. "He was between 30 and

35 years of age." A woman, her face obscured from view, was sitting in

the front seat, and Peg Cuttino, apparently alive and awake, was riding

in back seat on the right hand side of the car. The young man told

police that he waved to her, but that she apparently did not recognize

him. He also told authorities that he thought no more of it until he

heard word that the girl had vanished. Though authorities never doubted

the young man's sincerity, they also failed to identify the car, and

neither the mysterious driver nor his female passenger ever came forward

to support the young man's claim.

By the next morning, a small army of volunteers had

formed to scour the brush for Peg Cuttino. On Sunday, the third day

after the disappearance, the searchers paused to pray and on Monday,

more than a dozen men on horseback scoured a four-square-mile stretch of

woods just outside of the town of

Sumter. That evening, according to

published reports, just about supper time, three local radio stations

aired a brief prayer for her safe return, offered by the president of

the Sumter County Minister's Association. A lot of people apparently

listened. But it didn't help. For days the search for Peg Cuttino

continued and each day ended in frustration and deepening fear.

Still, local law enforcement officials tried to hold

out hope. In a statement widely reported in South

Carolina the next day, Sumter Police Chief

Leslie Griffin acknowledged that he could not rule out kidnapping and

had in fact issued a nationwide alert for the girl. But he added that "we

have not been able to discern any evidence which might indicate foul

play."

Somewhere, perhaps, some may have entertained the

secret and unspoken hope that maybe Peg Cuttino's prim demeanor had

misled them. Of course it would have been a bizarre irony, but what if

she had run away, or was simply hiding out somewhere as a youthful lark?

It would almost have been a relief if Peg Cuttino had

simply been touched by that rebelliousness that everything about her

seemed to defy.

But she wasn't.

On Dec. 30,

1970, 12 days after Peg Cuttino disappeared, two young

officers from nearby Shaw Air Force Base were riding their trail bikes

in

Manchester State

Forest when they came upon a figure

lying on the ground, partially covered with sticks and leaves. At first,

they thought it might have been a mannequin dumped in the woods as a

trash or as a prank. But then they spotted the polka-dot sash, which had

been described in detail in every news release and bulletin about the

missing girl. They raced to a nearby general store and summoned police.

The police arrived quickly, and so did three

pathologists from the Medical University of South Carolina at

Charleston.

The pathologists concluded that Peg Cuttino had been

bludgeoned to death with a blunt object, in all probability a tire iron.

The young girl in the modest white skirt, they said, had also been raped.

There were traces of semen -- some of it still fresh -- in her body.

The authorities also issued another conclusion that

would, in time, prove to be among the most controversial. Though they

conceded that they couldn't be certain beyond a shadow of a doubt given

the comparatively primitive forensic tools available to them at the

time, the authorities argued that in all likelihood, Peg Cuttino had

been raped and murdered on Dec. 18, 1970, probably within an hour or so

of her disappearance. There were some questions about that conclusion.

Despite the comparatively balmy temperatures in

South Carolina during late

December, some of the sperm found in her body had not significantly

degraded. That seemed to be an indication, according to at least one

forensic scientist, that whoever had raped and murdered the girl, had

done so not on Dec. 18, but later, perhaps as late Dec. 26, eight days

after her disappearance.

The authorities however, paid little heed to that

theory. They built their case on the premise that Peg Cuttino had been

taken from the streets of

Sumter and killed all on the same

day.

There was at least one person who was willing to

dispute that assertion. In fact, she's been disputing it for more than

30 years.

A Ghost in Flesh and Blood

It was Dec.

19, 1970, the Saturday before Christmas, and Carrie LeNoir,

part-time postmistress in the little farm

village of

Horatio, barely had time to look up

all morning as she labored behind the counter at the old general store-cum-fill-up

station-cum-post office that she ran with her husband. That morning,

before she sauntered into the post office from her house across the yard,

a relative had called and mentioned something about Peg Cuttino and her

disappearance, but the horror of the whole story hadn't really had time

to hit LeNoir before she found herself in a work frenzy, slapping stamps

on Christmas cards and weighing holiday packages.

It was 2:30 p.m. before

she finally got a chance to catch her breath. She decided to stroll back

to the house, and as she returned, she noticed a car, a "brownish-yellow

car," as she would later describe it, parked outside the store. As she

neared it, she noticed three young people, two boys and a girl, perhaps

in their teens, step out of the store and into the car. She did not, she

would later say, get a good look at the girl. Nor did she recognize the

two boys, which was, in and of itself, unusual. After all, the little

store and post office on the old farm-to-market road was hardly a draw

for strangers. She had planned to ask her husband if he recognized the

trio, but work intervened and she forgot all about the encounter until

later that afternoon when the two boys returned to the store and handed

her three dollars for gas. The girl was no longer with them, and, as

LeNoir would later put it, "the boys seemed excited."

A short time later, the local newspaper, the Sumter

Item, an afternoon paper, arrived at the store. A picture of Peg Cuttino

stared out from the front page. LeNoir's husband studied it. "That girl

was in the store today," he told his wife. LeNoir studied the girl in

the photograph as well, comparing her in her mind to the young woman she

had briefly glimpsed outside the store earlier that day. There were some

differences to be sure; the girl outside wore her hair about shoulder

length. The last time Carrie LeNoir could remember seeing Peg Cuttino,

her hair was long.

LeNoir and her husband mulled over their options.

They certainly didn't want to provide anyone with false information, and

wanted even less to offer false hope. The next morning, just to be sure,

she telephoned an acquaintance who also happened to be related to the

Cuttinos. She asked about Peg's hair, and when the relative told her

that Peg had been wearing her hair in a shoulder-length bob, Carrie

LeNoir related the chance encounter at the Horatio post office the day

before.

Later that day, the police came to visit LeNoir at

the nearby Church of the Ascension where LeNoir, the organist, was

rehearsing for the Christmas pageant that evening. It was a friendly

chat, LeNoir recalled in a recent interview with Court TV's Crime

Library, and when it was over, the detectives Hugh Mathis and Tommy Mims,

now sheriff of

Sumter County

-- closed their notebooks, thanked her for her time, and moved on.

It is not clear, even today, how much stock the two

detectives took in Carrie LeNoir's account of her chance encounter with

a young girl who looked, in hindsight, a great deal like Peg Cuttino. To

be sure, she was just one on a list of potential witnesses that swelled

to include 1,465 names. The list even included Pee Wee Gaskins. He had

been interviewed early on in the investigation by the same law

enforcement official for whom he had been working as a police informant,

sources close to the case say, and he was quickly ruled out as a suspect.

In short, Carrie LeNoir's statement was just one of

many statements given in the case, and it would later be discounted, in

large measure, some critics now say, because it didn't fit with

investigators' conclusions about the case.

What none of them realized, however, was that in

dismissing Carrie LeNoir's statement, they had taken the first steps

toward mobilizing a small army of crusaders who would spent the next 30

years casting doubt, much of it legitimate, on the state's case in the

matter of Peg Cuttino.

Confession is Good for the Soul

William "Junior" Pierce tossed his head back, cupped

his hands over his eyes and stared off toward some imagined horizon. He

let out a low, otherworldly moan and a guttural sound filled the cinder-block

room. It was the kind of sound the fortune-tellers at the carnivals that

used to visit Junior's small

Georgia town

would make just before they would claim they had a vision.

Junior loved to play this game with the cops.

Though he had an IQ that just barely broke 70, he had

always believed he was smart enough to make suckers out of the cops. He

seemed to think that he really could make them believe that he was

crazier, or dumber than he really was.

Of course, he hadn't had much success with the gambit.

The fact that he was sitting in a

Georgia jailhouse,

facing charges in nine separate murders, murders that had stretched from

Hazelhurst,

Georgia, to

West Columbia,

S.C., seemed proof that Pierce was not nearly

as good at the game as he thought he was.

There are some, his former lawyer among them, who say

that while Junior may have been violent, and may even have been a

murderer, it is not likely that Junior Pierce was a serial killer in the

classical sense. There is little doubt, however, that he was a serial

confessor. In fact, several of the cases against Pierce would later be

dropped, and in at least one of the cases, says Joe McElveen, who would

represent Pierce in the Cuttino case and later went on to become mayor

of Sumter, investigators discounted Pierce's confession altogether. In

that case, South Carolina investigators "went down to Georgia at some

point to look into a double murderthat Pierce confessed to," but after

interviewing Pierce, the disgusted sheriff said that he had no faith in

the confession and "didn't want to solve the crimes that way," McElveen

said.

But by April 1971, four months after Peg Cuttino's

killing, the authorities in

Sumter County,

who by then had been joined by the State Law Enforcement Division, were

getting desperate to solve the case.

Though they had conducted nearly 1,500 interviews,

and had tracked down scores of seemingly promising leads, several of

them out of state, they had come up empty. In the minds of the people of

Sumter, they were no closer to

solving the case than they had been the day she disappeared. That

worried them, and it deeply disturbed Sheriff Parnell and the other

investigators on the case.

Hugh Munn, then a young reporter for The State,

South Carolina's most prominent newspaper, and

later a spokesman for SLED, says he believes that Parnell and the others

working the Cuttino case were under immense pressure to close it. "I

just think there was a rush to get this thing resolved quickly, which

was always the way, and it still is in law enforcement," Munn said. "You

wantto tell the community; 'Look, calm down, everything's under

control.'"

They got their chance in April when Sheriff J.B.

"Red" Carter from

Baxley,

Georgia, picked up the

telephone and contacted SLED Chief J.P. Strom, telling him that he had a

good ol' boy in his jail who had a statement to make in connection with

Peg Cuttino's murder.

According to court documents and reports published

later in the Sumter Item, Pierce had made one of his overly dramatic

confessions, claiming he had driven to Sumter on

Dec. 18, 1970, the day that Peg Cuttino

disappeared, with the intent to "rob and steal."

According to his alleged statement, he stopped for a

bite at a drive-through restaurant not far from the center of town, when

he saw two girls and a young man embroiled in a bitter dispute. Pierce,

it is alleged, told authorities that he listened to the conversation "about

as long as I could take it," before he decided to intervene. He

allegedly claimed that he told the boy to leave, but the boy stood up to

him briefly after going to his car to fetch a chain, presumably to use

as a weapon. Not to be outdone, Pierce allegedly said that he went to

his old maroon Pontiac to get a gun, and when the boy saw the pistol, he

and the other young woman, drove off, leaving Peg Cuttino behind.

It has long been a subject of controversy that this

heated confrontation between Pierce and the boy seems to have gone

completely unnoticed by anyone in the small town of

Sumter. Though Pierce is said to have claimed

that he saw a woman watching the events unfold from inside the

restaurant, neither that woman, nor any witness has been able to

corroborate Pierce's alleged statement.

That, say critics of the state's case, would stretch

credulity under any circumstances, but it was particularly questionable

considering that the showdown is alleged to have taken place in the

middle of the day on the Friday before Christmas, at a time when the

streets of Sumter were filled with excited youngsters just out of school,

as well as shopkeepers and customers.

Equally questionable was Pierce's supposed claim that

as soon as the confrontation ended, Peg Cuttino, the Sunday school

student and choir girl, turned to the gun-wielding stranger and

volunteered to go with him, saying, according to reports of court

proceedings published later, "I'll ride with you."

No explanation for the girl's alleged behavior was

ever offered, despite the fact that it seemed to contrast sharply with

the public image of Peg Cuttino as a decent young girl, who, even she

did have a rebellious streak, would hardly have been foolish enough to

hop into a car with an armed stranger, especially one as odd as Junior

Pierce.

In his statement, Pierce is alleged to have said he

drove with the girl to a landfill at the edge of town. According to a

report published in the Sumter Item in the opening days of Junior

Pierce's 1973 trial for Peg Cuttino's murder, Sheriff Parnell recounted

that Pierce told authorities that he had parked at the landfill and, "the

little girl started crying and said she wanted to go home," and that

Junior, apparently fearing that police would be looking for him after

the confrontation outside the restaurant, told her, "I can't carry you

home."

"That's when he struck her in the head with a bumper

jack," a tire iron, the sheriff testified.

According to the statement, Pierce never explained

why the girl's mood seemed to have changed so abruptly, nor does he

explain why after killing her, instead of simply dumping her body in the

landfill, and perhaps covering it with trash, he drove a half-mile to a

wooded area and dumped her there, taking the time to cover her body,

however crudely, with leaves and moss and sticks. He is also said to

have claimed that moments after he finished covering Peg Cuttino's body,

he spotted two people walking through the woods, a man and a boy. One of

them had a rifle, presumably to hunt squirrels. Pierce allegedly claimed

that he stood behind the car in an effort to block his license plate

from view.

In fact, there were, according to later testimony,

two people in the woods around that time, a man and his son. The boy

would later testify that he was hunting squirrels when he spotted a man

standing suspiciously near his car and lingering there until the boy and

his father left.

To the authorities, the boy's testimony was powerful

corroboration. But to critics, even today, it still raises as many

questions as answers. One of those questions is the make and model of

the car. Though Pierce allegedly claimed that he was driving a maroon

Pontiac, the witness said the car he saw was a white Ford station wagon.

What's more, the boy testified that he saw the car on Dec. 19, the day

after Pierce allegedly confessed he had killed the girl.

Most troubling of all to the critics, Carrie LeNoir

among them, is the fact that Junior Pierce's alleged confession was

never put down on paper, and never recorded in any way.

Testifying on his own behalf, Pierce would later

disavow the confession, insisting that the entire confession was cobbled

together from pieces of information he had been fed by Baxley Sheriff

Red Carter before officers from

South Carolina arrived to

interview him. According to published reports of Pierce's testimony, he

claimed "that he knew details about the girl's death because Red Carter

had discussed the case with him and told him that if he made a statement,

he would never stand trial in South Carolina."

Later, Pierce claimed that he had been threatened with abuse bordering

on torture if he didn't confess. Those allegations, largely dismissed at

the time, gained greater currency among some of the people of

Sumter years later when Carter was

convicted in federal court for his part in a drug-trafficking scheme in

Georgia.

There were also questions about some of the physical

evidence in the case. Pierce's car, which he claimed he had abandoned at

a service station not far from his

Georgia home,

was never recovered. Nor was the tire iron that authorities believed he

used as the murder weapon.

Even today, Pierce's confession remains suspect in

the minds of many. As McElveen put it in a recent interview with Court

TV's Crime Library, "Something very fishy was going on in

Baxley,

Georgia, when he was being

held down there."

All the same, it was good enough for the authorities

in

Sumter.

Trial and Error

Even among those who have spent years trying to

exonerate Junior Pierce for the murder of Peg Cuttino, there are many

who acknowledge that the men who pursued and prosecuted him were, by and

large, honorable men.

Among them is Ken Young. Formerly an assistant county

solicitor who worked closely on other cases with the late Kirk McLeod,

the man who prosecuted Pierce, Young is now representing Pierce as he

seeks, once again, to overturn his conviction.

"Kirk and I were very close," Young said in a recent

interview. "I don't think he would ever lie and he (was) convinced

thathe had the right man.

"He based that on complete and total reliance on what

Sheriff Ira Byrd Parnell told him and what (SLED Chief) Strom had

told him," and they in turn had placed their faith in Pierce's alleged

confession, though Young now believes that confession was tainted. "According

to Junior Pierce, he was told what to say by the sheriff down in

Georgia," Young

said. "These fellows went down there, there was a lot of pressure to

solve the case and I think that they heard this man give them enough of

the answers to convince them that they had the right man. That's all

they needed to hear."

The trial began on

March 1, 1973, but not in

Sumter County.

Pierce's lawyers had successfully argued that the public furor

surrounding the case was such that Pierce had no chance of getting a

fair shake from a jury in

Sumter and so the case was moved to

Williamsburg

County.

It was expected to last two days. As it turned out,

that was a reasonably accurate estimate.

During about a day-and-a-half of testimony, the

prosecution focused on Pierce's testimony, and according to critics,

glossed over the inconsistencies and weaknesses in their case, the lack

of witnesses to the crucial Dec. 18, 1970, confrontation outside

the restaurant during which Pierce met Peg Cuttino. They also downplayed

the absence of the murder weapon or any other physical evidence linking

Pierce to the crime. Nor did they pay any particular attention to the

discrepancies in the testimony of the boy who claimed to have seen a man

in the woods sometime not long after Peg Cuttino had disappeared,

discrepancies that included the make and the model of the car parked in

the woods, and the time at which he had allegedly seen it.

The defense, in retrospect, did little to challenge

those inconsistencies either. Instead, McElveen, a young lawyer fresh

out of the military trying his first murder case, and his co-counsel

focused on what they believed to be a critical piece of evidence.

Drawing on the testimony of Junior Piece's boss at the Swainsboro,

Georgia, factory

where he worked, they tried to prove that Pierce could not possibly have

been in

Sumter on the day that Peg Cuttino

disappeared.

According to McElveen, Ray Sconyers, vice president

of the Handy House Corporation, testified that he personally handed

Pierce his time card at about 7:05 a.m. on the morning of Dec. 18, 1970,

and that he had seen Pierce about once every hour during the day, and

that he had personally handed Pierce his paycheck around 4 p.m. What's

more, Pierce's girlfriend, who had testified against Pierce in three

separate trials, told the court that she had been with him, along with

two other witnesses, all night on the evening of

Dec. 18, 1970. It would have been

impossible, McElveen said, for Pierce to travel the roughly 200 miles to

Sumter on the day, kill Peg Cuttino

and then return, all on the same day. "They pinned their case on her

having been killed on the same day that she was taken andwe proved he

was back inSwainsboro that night." McElveen said in a recent interview,

adding that he was convinced that the testimony of Sconyers and Pierce's

girlfriend would skewer the prosecution's case.

Then McElveen went after the confession. He allowed

Pierce to testify that he had been forced to talk and that, even then,

he had never actually admitted to killing the girl, and that authorities

had twisted his words. McElveen said he was confident that "we did a

pretty good job of dissembling (sic) the confession because we were able

to show that everything that wasin this remarkable, revealing confession

was in a newspaper somewhere, andthat they changed it (to make it) a

little bit better every time they testified," McElveen said.

In what was to have been McElveen's most audacious

gambit, the lawyer employed the services of a nationally noted hypnotist

named Robert Sauer. Sauer had, over the years, worked from time to time

with law enforcement agencies, and had even worked with SLED briefly on

the Cuttino case. He had been called into to help interview one

potential suspect, who, after being hypnotized by Sauer, was dropped

from the list.

Sauer, however, was not permitted to testify. Had he

been, jurors would have learned that under hypnosis, Junior Pierce had

denied killing Peg Cuttino or even being in Sumter County at or about

the time of her disappearance. In fact, McElveen said, Pierce was not

even certain where

Sumter County

was. In McElveen's mind, the interview under hypnosis would have been a

crucial element of the case. Sauer had even gone so far as to add what

he described as a built-in lie detector to the hypnosis regimen, urging

Pierce's subconscious to make him raise one finger if he tried to lie.

That test, McElveen said, convinced him that Pierce was telling the

truth when he recanted his confession.

But the jury never heard it.

About 6 p.m. on

Friday, March 2, after less than 16 hours of testimony, the jury began

deliberations. About 6 hours later, they returned with a verdict.

William "Junior" Pierce was found guilty of murder.

He was sentenced to life in prison, though in truth, the sentence made

little difference. He was already serving life for murder in

Georgia and it

was unlikely that Junior Pierce would ever see the inside of a

South Carolina prison.

Justice Undone

If authorities in

Sumter County

were hoping that the conviction of Junior Pierce would ease the public's

fears, that it would bring closure to the tragedy of Peg Cuttino and

restore the public's flagging faith in them, they would soon discover

that they had been hopelessly wrong.

"I can understand why they wanted to do it," said

Munn, now an instructor at the

University of South

Carolina. "I think in this particular

casethey (wanted) to say, 'We believe we got the right man, we've got

the evidencehe's confessedlet's get it over with."

But, by all accounts, they underestimated just how

deeply the case had shaken the community. Within days of the conviction,

letters to the editor started to appear in the local newspaper, letters

that seemed to suggest that Junior Pierce, though hardly an innocent man

in the grand scheme of things, might have been railroaded in the Cuttino

case.

Of course there were some, most of them well-connected,

who believed, or at least insisted publicly, that justice had been done.

Chief among them was James Cuttino, the slain girl's father. Until his

death several years ago, Cuttino remained firm that the right man had

been convicted. But even the grieving father's insistence did little to

douse the smoldering dissent in

Sumter.

Hubert Osteen, president of the Item, who was an

editorialist at his family-owned paper at the time, said recently that

the fallout over the case drove, for the first time, a wedge between the

authorities, people like Kirk McLeod, who had prosecuted the case, and

Sheriff Parnell, and the community at large, and may even have touched

Cuttino himself.

"Up until that time, there was no mistrust of the

authorities," Osteen said. "The sheriff had been in office for 20-something

years. He could do no wrong, and then this thing broke. That's when

people started questioning his case".

And no one questioned the state's case more vocally

or persistently than Carrie LeNoir.

As Munn put it, at precisely the moment that the

authorities believed they put the case to rest, "Carrie LeNoir steps in

and she throws in some pretty compelling arguments."

The way LeNoir saw it, the state's case against

Pierce was flawed from the beginning. The case, as McElveen has said,

was largely based on the presumption that Peg Cuttino had been killed

almost immediately after her disappearance on

Dec. 18, 1970, though the

forensic science of the time was hardly precise enough to accurately pin

down the date within a span of more than several days.

Yet Carrie LeNoir insisted that she had seen Peg

Cuttino at the general store and post office on the afternoon of Dec.

19. She had told that to investigators, she said, and yet the

prosecution apparently ignored her statement. In fact, McElveen and his

co-counsel were never informed of LeNoir's statement and didn't learn of

its existence until days after the trial.

Also overlooked was the eyewitness account of Peg

Cuttino's classmate who had seen her riding in the back of a light-colored

Mercury Comet with a man in sunglasses and a strange woman. The sighting,

according to the student, occurred at about the same time that, if the

prosecution's allegations were to be believed, Peg Cuttino was on her

way to the landfill where she would be slain by Junior Pierce. Taken

together with the testimony that had been included in the trial, which,

according to the critics, conclusively proved that Pierce was in

Georgia at the

time of the killing, the new revelations fueled even greater suspicion

about the validity of the state's case.

Within a month of the trial, those doubts had reached

critical mass, and on April 5, McElveen and his team laid out their case

for a new trial in court, arguing, among other things, that if the jury

had been privy to the statements of LeNoir and the witnesses, they

almost certainly would have voted to acquit.

The judge, however, saw things differently. He

refused to grant a new trial.

But rather than end the controversy, that decision

only fueled the suspicion. For the first time, at the lunch counters and

coffee shops of

Sumter, people were starting to use

the word "cover-up." Rumors, ugly and unfounded though they might have

been, began circulating. Once again, the notion that somewhere out in

the woods, there was a trailer where well-connected youngsters were

exploited by

Left Coast

pornographers began to circulate. Perhaps, it was whispered, Peg Cuttino

had been a victim of that ring. There was, of course, never any proof of

any such cabal, but the idea that such rumors could take root at all was

a clear indication of just how frayed the public trust had become in the

wake of Peg Cuttino's death.

Breaking Ranks

The controversy, as it would soon turn out, was not

confined to whispered doubts on the streets of

Sumter. Even one of the men who had worked on the

case, Howard J. Parnell, coroner and nephew to the sheriff, had grave

concerns about the case and in June 1973, he went public. The truth was,

he had always doubted that Pierce was guilty. But as the public clamor

grew, Howard Parnell joined it, claiming that he had unearthed new

evidence in the case, evidence that presumably would have cleared Pierce.

He demanded a meeting with Sheriff Parnell, with the chief of police and

other local officials, including McLeod, the solicitor and SLED Chief

Strom.

The meeting ended abruptly, to put it charitably when

Coroner Parnell, a funeral director by trade, stormed out, shouting,

according to published reports at the time, "I'm through! I'm through,"

and claiming that he had been ambushed by what he described as "a

hostile group."

Howard Parnell recounted the meeting in a recent

interview with Court TV's Crime Library, acknowledging that the evidence

he had planned to present in large part duplicated the information that

already had been made public, some it during Pierce's trial, about the

suspect's movements on the days surrounding Peg Cuttino's death.

Far more damning was his allegation that the

officials at the meeting in essence urged him, in his words to "just go

along and forget about this and we'll promise you that your funeral home

will get business."

To this day, Howard Parnell believes that he was

punished for his refusal to support Pierce's conviction. He contends

that he was effectively "run out of town." He bases that allegation

chiefly on the fact that three banks subsequently rejected his

applications for mortgages in the days following the controversial

meeting.

The authorities, of course, had a far different

version of the events that day.

"There were no hard feelings, I even got up and shook

his hand when he came in," Sheriff Parnell told reporters after the

session. According to the sheriff, the meeting ended because his nephew

"had no new leads, and we reassured him if he had anything we would

cooperate and help him in any way we could."

That reassurance did little to assuage Howard

Parnell's anger. Soon after he quit his post as coroner and left town.

And it did even less to reduce the simmering mistrust in the community.

The Grand Jury

Within a few weeks of the ill-fated meeting, perhaps

in a nod to mounting public pressure, the authorities decided to put the

whole matter before a grand jury. "It is high time and quite proper that

you check this off the books of

Sumter County,"

Third Circuit Judge Dan F. Laney told the grand jurors in his charge to

them.

If that was the goal to put the matter to rest once

and for all it failed.

When the grand jury announced its decision that "no

substantive evidence had been presented which would support a finding of

either incompleteness or impropriety on the part of public officials

charged with the investigation of the (Cuttino) case," LeNoir, Howard

Parnell, and others who had turned the case into a crusade were outraged.

"They think it's over," LeNoir said at the time. "They

think they've cleared the names and reputations of all the individuals

in law enforcement and all the law enforcement agencies involved."

But as far as LeNoir was concerned, it was far from

over.

For the next several years, as the courts all the way

to the state Supreme Court continued to reject Pierce's appeals and his

bids for post conviction relief, and as a second grand jury failed to

reopen the case, Carrie LeNoir waged a relentless battle that took her

from the streets of Sumter to the federal Justice Department in

Washington, D.C., trying to find help in her crusade.

She found none, but rather than dull her ardor, that

only deepened the sense of LeNoir and others that they were fighting a

battle that was as much about politics as it was about justice.

During the course of that battle, she even found

herself at odds with James Cuttino, the dead girl's father. Among the

documents that LeNoir had collected were autopsy photographs of Peg

Cuttino, along with information regarding the discovery of intact semen

in the dead girl's body, evidence, she contends, that Peg Cuttino could

not possibly have been killed on Dec. 18, evidence that, she believed,

undercut Junior Pierce's supposed confession and threw in doubt most of

the testimony from the state's witnesses.

She was, she admits, not shy about showing that

information to anyone when she thought it might advance the case she was

trying to make. Cuttino, who according to those who knew him, was not

only convinced of Junior Pierce's guilt, he was desperate to at last put

the whole sordid matter to rest and LeNoir and others believe it was at

his insistence that the courts went after her, demanding that she turn

over the documents she had collected. Cuttino had argued that LeNoir was

"trespassing on (Peg Cuttino's) memory." At first LeNoir refused. She

was even sentenced to 90 days in jail, though the sentence was suspended

pending appeal. Ultimately, she agreed to return the documents to the

court, where they were placed under seal.

In 1977, the bizarre case took yet another bizarre

turn when Donald Henry "Pee Wee" Gaskins, the South's worst serial

killer, was at the time already convicted of one murder, indicted for

many more murders, and was standing trial for the murder of another in

Florence County, made the shocking announcement that he, not Junior

Pierce, had abducted and killed Peg Cuttino.

Pee Wee's Playhouse

Over the years, Gaskins gave at least two accounts of

the killing. In one particularly sordid version, he claimed to have been

part of a murder-theft ring that he claimed was operating with the

knowledge of police officials in

South Carolina. The killer claimed

that he had been hired by a never named law enforcement officer to "assassinate"

Peg Cuttino. No evidence to support that claim was ever uncovered. In

another version, later included among his vain and venal statements in

the book, The Final Truth, Gaskins claimed that he had killed Peg

Cuttino because during a chance encounter on the street, she had

insulted him, telling her friends that he was "white trash."

For many in

Sumter County,

there were a great many reasons to believe Pee Wee Gaskins. He certainly

had the capacity to kill. That much was not in question. He also had

what McElveen would later claim was a far greater opportunity to kill

Peg Cuttino. He was, after all, living in Sumter

at the time of Peg Cuttino's murder, and in fact, had been working as a

roofer at the YMCA building a few yards from the spot where the girl was

last seen alive. What's more, there is little question that he was

working as a police informant at the time, and his name was even on the

list of witnesses who were questioned in the first frantic hours after

Peg Cuttino's disappearance.

There are also indications that he might have had

access to a car similar to the one Peg Cuttino was said to have been

seen riding in on the day she died. And there were also tantalizing

details that he was able to provide about the case. He noted for example,

a small array of burn marks on Peg Cuttino's arm, marks that authorities

had identified as cigarette burns. Gaskins claimed that they were acid

burns, that he had dripped the caustic liquid liquid he would have had

access to in his job on the dying girl's body.

But there were plenty of reasons to question the

supposed confession as well.

Pee Wee Gaskins, a notorious liar, had some kind of

book deal he was negotiating. Adding the Cuttino case to his crimes

would have enhanced his position. What's more, Gaskins and Pierce had

been corresponding while both were in prison. Gaskins himself, described

by many who knew him as a classic manipulator and a keen student of the

flaws in the judicial system, would later recant his confession. He

claimed, according to court documents, that he made the stunning

confession because "there was a lot of pressure put on me and I

figuredsaying a lot of that would get a lot of pressure off me."

He also said he "felt that if I went into it and said

I killed her and everything, that would take pressure off of Pierce. He

was wanting to get from under thatI got letters from him."

Both the confession and the retraction would remain

controversial. In separate letters to Pierce and LeNoir, with whom he

was also corresponding, Gaskins would later insist that his retraction

not his confession was made under pressure from authorities.

The entire dispute would be aired in 1983 when a

court agreed to hear yet another appeal on Pierce's behalf, this one,

claiming among other things that Gaskin's confession was grounds to

overturn his conviction.

The appeals court, declined, and as had every other

court that had heard the case, it upheld Pierce's conviction.

In essence, it seemed, the court found Gaskin's

statements incredible.

It's not surprising that one of those who agrees with

the court's decision, if only in that aspect of the case is Ken Young.

In the 1970s, Young was the assistant solicitor who

prosecuted Gaskins in the

Florencecase. During that trial, he

says, he struck up a rapport with Gaskins, a rapport that lasted until

Gaskins was executed years later for an unrelated homicide. Young says

he was convinced that as deadly as Gaskins was, he was not Peg Cuttino's

killer. "He didn't know beans about the case," Young told Crime Library

in a recent interview. In fact many of Gaskins statements about the

case, including the details about the burns on the girl's arm, "were in

the paper," Young said. "Pee Wee Gaskins was probably one of the

smartest criminals you'd ever want to meet. He was amazing. But no, I

don't believe he killed Peg Cuttino. In fact, in front of his lawyers on

death row, he told me, 'By the way, I never killed Peg Cuttino.'"

What is surprising is that Young, now in private

practice, is one of those who firmly believe in Junior Pierce's

innocence. In fact, he is currently representing Pierce and is preparing

a draft of an order for post-trial relief in the case, though he didn't

choose the case, it was assigned to him. Among the issues Young plans

to place before the court in the idea that critical information

including details of the autopsy report were wrongly withheld from the

defense.

"I don't believe they disclosed to the defense

counsel all of the autopsy reportsthat the semenhad the tails," he said.

"My expert, she's made the casethat there's no way that they could have

been placed in the body at the time that was claimed by the state,

December the 18th." Young also contends that evidence,

available at the time but apparently not shared with the defense

indicates that "fromthe position of the body and the fact that the sperm

still had tails on them that the earliest date that she could have the

time of death would be December 26."

But Young also plans to argue that Junior Pierce's

first defense team failed him as well.

As Young puts it, McElveen and the others were so

focused on the task of establishing that Pierce was in

Georgia, not

South Carolina at the time of Peg

Cuttino's death, that they missed the chance to uncover some of the

facts that might have led them to the pathologist's report.

"The defense put all of their eggs in one basket,"

Young said. "When they went and looked at the autopsy report, they

only looked at the first page. They weren't interested in looking at

anything beyond that," Young said. "If they had looked at the entire

document, they would have seen these (semen samples) and at least asked

for a blood test or something to exclude him. You didn't have the DNA

tests back then, but they had tests that could haveruled him out. At

least they could have tried that."

In one final irony of the case, while the technology

exists now to prove almost conclusively whether the semen recovered 30

years ago from Peg Cuttino's body matches Junior Pierce's DNA, or

whether it points to another killer, the samples themselves, no longer

do.

"When I first got assigned this caseI said, 'Well, we

got DNA now, we'll solve this thing right quick. So I started pressing (officials

at the Medical University of South Carolina where the samples were to

have been stored) to give me the autopsy results. You know everything

was on slides, so I thought I could find that."

But when Young finally showed up at MUSC, "they took

me to a parking garage in the basement, (where there were) all these

rows and rows of filesI inventoried them, I went through them one by one,

figuring that maybe something was out of place. The only drawer, the

only drawer in the entire group that was missing was the one containing

(the samples drawn from the body of) Peg Cuttino."

To some, there could be a thousand innocent

explanations for the missing files. They could have been destroyed by

fire, as were other state records, they could have fallen victim to one

of the many hurricanes that wreak havoc on that part of the country,

they might have even have been accidentally discarded, victims of the

changes that have taken place in file management over the years.

But Young says he remains suspicious.

The way he sees it, the missing files are a pretty

strong indication that "somebody's trying to impede my investigation of

this".

Lingering Questions

Whether the court ultimately sides with Young and

Pierce is anybody's guess. For the past 30 years, every court that has

examined the case has upheld Junior Pierce's conviction, and there are

many who believe in his guilt.

Even Hugh Munn, who as a young reporter at The State,

crafted with his partner, the late Jack Truluck, an award winning series

of reports questioning the state's evidence, says he believes that, in

the end, Junior Pierce was rightly accused.

"When I was at the newspaper, even after we went

through all of this laborious stuff that Jack and I didI was more

inclined to think that he did than he didn't. But there was this doubt.

This nagging little doubt." Munn said. Later, as spokesman for SLED, "over

the next few number of years, I talked to some of the players who are

now no longer around, I was more inclined to believe that he did it,

with maybe just a hint of a doubt, but not enoughI kind of think he did.

But I think (the investigation) was just handledpoorly."

But there are others who remain even more firmly

convinced that Pierce is innocent, at least of any complicity in Peg

Cuttino's death. But if Junior Pierce didn't do it, and if Pee Wee

Gaskins was lying when he claimed to have been the killer, then who did?

There are as many theories as there are doubters, it

seems. Perhaps a drifter killed her. Perhaps the killer was among the

hundreds of transient men somehow linked to the nearby Air Force base,

the same Air Force base that housed the two officers who first stumbled

across Peg Cuttino's body in the woods.

There are other tantalizing possibilities as well,

said Young. "There was a fellow in Columbiawhocommitted

two similar crimes," he said. In both cases, the bodies were dumped in

shallow graves. The suspect "eventually died in

California," Young said. "I think

one of the best leads was him." But so far, Young said, "I can't put

anything together."

Even Carrie LeNoir has theories about who might have

killed Peg Cuttino. But for the time being, she says, she plans to keep

them to herself. To her, the case is more than a simple whodunit. For

three decades, despite setbacks and disappointments, it's been a kind of

a crusade.

"Even if I knew (who) did it, I'd be foolish to say

sountil we can get (Pierce) exonerated," she said. For now, she said, "I'm

not interested in finding out who did it." Instead, she insists that she

is interested only in reversing what she believes to have been a gross

miscarriage of justice. "It's just not fair," she said. "If they did

that to William J. Pierce, they could do that to any one of us."

Coerced Confession

Crime Library Executive Editor Marilyn Bardsley

recently received this document dated October 2, 1971 written by Georgia

State Prison's Dr. Schlinger who was asked to investigate injuries

inflicted on William Pierce Jr. during his April, 1971 questioning at

the Appling County, GA, jail.

This document appears to substantiate William

Pierce's allegation that his confession to the Peggy Cuttino murder was

coerced by physical abuse consisting of burns, bruises, and cuts to his

"privates." Had this document been provided to attorneys representing

Pierce before his trial, it seems unlikely that, with the other evidence

exculpating Pierce that was never presented at his trial, he would not

have been convicted of the murder of Peggy Cuttino.

CrimeLibrary.com