Ronald Joseph Ryan was born on 21 February 1925

at the Royal Women's Hospital in Melbourne's inner suburb of

Carlton, to John (aka Big Jack) and Cecilia Thompson. Cecilia

already had a son with her first husband George Harry Thompson and

was living with John Ryan. Cecilia and George had separated in

1915 when George left to fight in the Great War. The relationship

never resumed. Cecilia met John Ryan while working as a nurse in

Woods Point where he was suffering lung disease. They formed a

relationship in 1924 and later married after Thompson's death in

1927 from a car accident.

In 1936 Ryan was confirmed in the Catholic

Church. He took as his confirmation name Joseph, and then became

known as Ronald Joseph Ryan. The family lived in dire poverty.

When Jack was completely unable to work due to lung disease and

with most of his invalid pension spent on alcohol, the family move

to a tiny cottage in Brunswick and things became even more

desperate. Severe, neglected ulceration leaves Ronald almost blind

in his left eye, which causes a slight droop to his damaged eye.

Finally Mrs Ryan can no longer keep the state child welfare

authorities at bay.

The Ryan children are made a ward of the state

after authorities declared them as "neglected". At the age of ten

Ronald Ryan is sent to the Salesian Brothers' Orphanage at Sunbury,

on the outskirts of Melbourne. His sisters (Irma, Violet and

Gloria) were sent to the Good Shepard Convent in Collingwood.

Ryan did quite well, captaining the football

and cricket teams, joining the choir, and impressing other boys as

'a natural leader'. Ryan absconded from Rupertswood in September

1939 and joined his half-brother George Thompson, working in and

around Balranald, New South Wales, spare money earnt from sleeper

cutting and kangaroo shooting was sent money to his mother looking

after their sick alcoholic father John Ryan.

At the age of eighteen, Ryan returns to

Melbourne from Balranald and picks up his three sisters from the

convent and buys them new clothes. Excitedly, he tells his sisters

about the wide-open space in the "outback", and his plans to move

them and their mother away from the violence and bad memories of

the big city. Later that year, after months of hard work to prove

his ability to support his sisters, the state child welfare

authorities agree to young Ronald's plans. That Christmas the

family are joyfully reunited at Balranald. Ryan is now the sole

breadwinner for the family. While his sisters go to school and his

mother looks after the house, Ryan takes on some farm work as well

as his other jobs. Ryan's father Jack, stayed in Melbourne and

died after a long battle with miners' phthisis turberculosis a

year later. Ryan worked to support his mother and sisters.

Aged about 23, Ryan returned to Melbourne where

he was employed as a storeman. On 4 February 1950, Ryan married

Dorothy Janet George at St Stephen's Anglican Church in Richmond.

She was the daughter of the Mayor of the Melbourne suburb of

Hawthorn - a prominent figure in local government, from an old

Melbourne family. Ryan's origins are firmly working class. Ronald

and Dorothy then have three daughters, Janice, Wendy, Rhonda and

Robert (died a few hours after birth).

Although Ryan had no trade, he was a versatile

worker, managing to support a wife and three daughters. Each

summer he works as a timber-cutter for a man named Keith Johanson,

a logging and pulpwood contractor in the mountains near Matlock,

eighty miles from Melbourne. Gradually, Ryan worked up to a

position as sub-foreman, responsible for paying and organising a

number of other men. Every second weekend, Ryan hitch-hikes home

to Melbourne with a cheque for his family, but the precious hours

with his wife and daughters are never long enough. Early Monday

morning he went back to work in the forest.

Ryan works harder than ever, earning the

respect of his employers and the men under him. When his daughters

begin attending school and the timber-cutting season ended, there

is not enough money. Ryan, now aged 31, is too proud to ask

Dorothy's parents for financial help and instead begins to gamble

heavily and passing forged cheques. He is soon caught and he

pleads guilty. Ryan is released on a five-year good behaviour bond.

In one report a detective describes Ryan as "highly intelligent".

Ryan worked in a series of straight jobs closer to home. For three

years he avoided crime, instead turning to gambling as a way to

give his family what he believed they deserved. However this

inevitably leads Ryan to store-breaking, then stealing, then

factory-breaking. Again he is caught.

Ryan's Life

Ryan was a small-time criminal, with no history of violence.

Unlike many criminals, Ryan's police record did not begin until he

was 31 years of age. Ryan was first sent to prison for robbery. He

had overcome the temptation to fall into a criminal life during a

difficult upbringing, only to stumble in maturity. Ryan's troubles

began when he tried to live up to the social level of his wife's

family, who were wealthy business people. In desperation Ryan

turned to gambling, switched from manual work to passing bad

cheques, received stolen goods, shopbreaking and burglary.

Ryan first served prison time at Bendigo Prison. His time in

prison was productive and he exhibited a disciplined approach to

study, completing his Leaving Certificate (year 11). Ryan was

studying for his Matriculation Certificate (year 12) when he was

released on parole in August 1963 He was regarded by the

authorities as a model prisoner. Appearing to want to rehabilitate

himself.

According to his wife Dorothy, in the

documentary film The Last Man Hanged Ryan wanted to provide

everything for his family and his gambling escalated. Ryan

returned to crime. On 13 November 1964, Ryan received an eight-year

prison sentence for breaking and entering. He was sent to

Pentridge Prison.

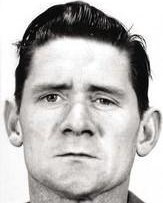

Slightly built and 5 ft 8 ins (173 cm) tall,

Ryan was a stylish-if spivvy'-dresser, who usually wore expensive,

well-cut suits, silk tie and a fedora. He was always keen to

impress as a man of means and consequence. He was of above-average

intelligence and was described by not only the people who knew him,

but also prison authorities, as a likable character with dignity

and self-respect.

Prison Escape

After Ryan was sentenced to Pentridge Prison, he was placed in 'B'

Division where he met a fellow prisoner Peter John Walker (who was

serving a 12 year sentence for bank robbery). When Ryan was

informed that his wife was getting a divorce, he made a plan to

escape from prison. Walker decided to go along with him. Ryan

planned to take himself and his family and flee to Brazil, where

there was no extradition treaty with Australia.

At around 2:07 p.m. on Sunday 19th December

1965, Ryan and Walker put the escape plan into effect. As prison

officers were taking turns attending a staff Christmas party in

the officers' mess hall, Ryan and Walker scaled a five-metre

prison wall with the aid of two wooden benches, a hook and

blankets. Running along the top of the wall to a prison watch

tower, they overpowered prison warder Helmut Lange. Ryan took his

M1 carbine rifle. Ryan quickly pulled the cocking lever of the

rifle and released it, forcing one round to spill onto the floor

of the watch tower. (The issue of the spilled round would become a

significant issue at trial). Ryan threatened Lange to pull the

lever which would open the prison tower gate to freedom. Lange

pulled the wrong lever. Ryan, Walker and Lange then proceeded down

the steps but the gate would not open. When Ryan realised Lange

had tricked him, Ryan jabbed the rifle into Lange’s back and

marched him back up the stairs so Lange could pulled the correct

lever to open the tower gate, the two escapees exited the gate out

into the prison car park.

Just in front of the duo was prison chaplain

Salvation Army Brigadier James Hewitt, The escapees grabbed him

and used him as a shield. Ryan armed with the rifle pointed it a

Hewitt and demanded his car. Prison Officer Bennett in Tower 2 saw

the prisoners, Ryan called Bennett to throw down his rifle,

Bennett ducked out of sight and then got his rifle. Walker had

dropped his pipe and had moved to the next door church. Prison

officer Bennett had his rifle aimed at Walker and ordered Walker

to halt or he would shoot. Walker took cover behind a small wall

that bordered the church.

The prison alarm was raised by Warder Lange,

and it began to blow loudly, indicating a prison escape. Armed

prison officers (every prison officer was issued with a prison-authorized

M1 Carbine rifle), including Paterson, came running out of the

prison main gate, onto the street.

George Hodson who had been having lunch in the

prison officers mess near the number 1 post responded to Lange’s

whistle. Bennett shouted to Hodson he had a prisoner, Walker,

pinned down behind the low church boundary wall. Hodson headed for

Walker and picked up Walker‘s pipe. Hodson grabbled with Walker

but the escapee managed to break free so Hodson began hitting the

fleeing Walker over his head with the piece of pipe. This wasn't

the first time that Hodson used violence against a prisoner. The

Truth Newspaper published letters from ex-prisoners claiming that

Hodson was a violent heavy-weight bully who would bash prisoners

with phone books, as not to leave marks on their bodies. Hodson

was separated from his wife and daughter and living in a flat in

the red-light center of Inkerman Street, St Kilda. The area was

notoriously known for street prostitution and illegal narcotics.

Walker was faster runner than Hodson, so Hodson continued to chase

after Walker with the pipe still in his hand. Walker was faster

runner than Hodson, so Hodson continued to chase after Walker with

the pipe still in his hand. Both men ran towards the armed Ronald

Ryan.

Meanwhile, confusion and noise was gaining

strength around the busy intersection of Sydney Road and O'Hea

Street, with armed prison guards on the street, on prison watch

towers and standing on low prison walls, vehicles and trams

banking up and people running between cars.

Frank and Pauline Jeziorski were traveling

south on Champ Street and had slowed to give way to traffic on

Sydney Road when Ryan armed with the rifle appeared in front of

their car. Ryan threatened a car driver and his passenger wife to

get out of their car. The driver Frank Jeziorski, turned his car

off, put it in neutral then got out of his car. Ryan got in via

the drivers door. Amazingly, Pauline Jeziorski refused to get out

of the car. She was persuaded by Ryan to get out of the car, only

to get back in the car to get her handbag. Ryan discovered he

could not drive the car because Jeziorski had modified the cars

gear linkages.

In frustration, Ryan with the rifle forced

Mitchinson to back off, then got out the passengers side door and

noticed Walker running towards him, being chased by Hodson who was

holding the pipe in his hand. Walker was shouting frantically to

Ryan that prison guard William Bennett, standing on the number 2

prison tower, had his rifle aimed at them. At this time, Hodson

was running close behind Walker, who was near Ryan.

In scenes of noise and confusion, a loud whip-like

crack of a single shot was heard, and a prison officer George

Hodson fell to the ground. He had been struck by a single bullet,

travelling from front to back, in a downward trajectory angle (suggesting

the shot had been fired from a high angle). The bullet had exited

through Hodson's back, about an inch lower than the point of entry

in his right shoulder. Hodson died in the middle of Sydney Road.

Ryan and Walker ran past the fallen warder and

commandeered a blue vanguard with Walker driving the car drove

through the service station and drove away on Ohea Street.

(Reference: Supreme Court Trial Transcript -

Queen v. Ryan & Walker, March 15-30 1966)

Ryan, Walker were extradited back to Melbourne. They were jointly

tried for the murder of George Hodson. It is alleged that Ryan

made three verbal confessions to police whilst being extradited to

Melbourne. According to police, Ryan admitted to them he had shot

prison officer Hodson. However, these verbal allegations were not

signed by Ryan and he denied making such verbal or written

confessions to anyone. The only signed document by Ryan was that

he would give no verbal testimony.

Walker was

also tried for the shooting murder of Arthur James Henderson

during the period when he and Ryan were at large.

Trial

and sentencing

On 15 March

1966, the case of The Queen v. Ryan and Walker began in the

Supreme Court of Victoria. Justice John Starke instructed the jury

of 12-men to look at the realities of things and ignore all that

they had read and heard about the case in the media.

The Crowns case

The crown's case relied heavily on eyewitnesses who were near the

Pentridge Prison when Hodson was killed. The big surprise was

that the rifle in Ryan's possession was never scientifically

examined by forensics to prove it had fired a shot. Instead of

the rifle being subject to careful storage and ballistic testing,

it had been inadequately stored in the boot of a police officer's

car where it was subject to contamination by dirt and dust.

Police testified that the M1 carbine rifle

stolen by Ryan from Lange "looked as if" it had been fired,

but there was no conclusive evidence that the rifle commandeered

by Ryan had been fired at all. It was noted that neither the

bullet that killed Hodson nor the spent cartridge case were ever

found despite intensive search by police.

There were fourteen eyewitnesses and each had a

different account of what they saw. All fourteen eyewitnesses

testified they saw Ryan waving and aiming his rifle. Only four

eyewitnesses testified that they saw Ryan fire a shot (a spent

cartridge would have had to spill on the ground, but a spent

cartridge was never found despite extensive search by police.) Two

eyewitnesses testified they saw smoke coming from Ryan's rifle.

Two eyewitnesses testified they saw Ryan recoil his rifle. A

ballistic expert on firearms testified that type of rifle was

coiless and it contained smokless cartridges.There were

contradicitions also, whether Ryan was standing, walking or

squatting at the time a single shot was heard, and whether Ryan

was to the left or right of Hodson.

All of the fourteen eyewitnesses testified that

they heard only one shot - no person heard two shots.

Prison officer Paterson testified he fired a

shot, and he was also the only person to claim to heard two shots

fired. At trial, Paterson was questioned about how he used his

rifle when he fired a shot. Paterson replied; "I took aim, I

took the first pressure that you take on the trigger, and I was

beginning to squeeze the trigger when a woman got into my sights,

and I could not withdraw my pressure from the trigger, so I had to

let the shot go in the air, and I don't know where the woman came

from she just appeared in my sights." the spent cartridge from

Paterson's rifle was never found by police either.

Paterson had contradicted in several statements

he made to police about what he saw, heard, and did on that day.

His first statement given to Detective Sergeant Carton on 19

December 1965 Paterson said; "I did not hear a shot fired other

than the one I fired." In a second statement given to Senior

Detective Morrison on 12 January 1966 Paterson said; "Just as I

turned into the entrance to the garden I heard a shot." In a

third statement on 3 February 1966 Paterson said; "I ran back

inside and asked for a gun, I went to the main gate and I received

a gun and ran back outside, as I was running on to the lawn I

heard the crack of a shot."

Paterson changed his story, too, about who was

in the line of fire when he aimed his rifle. In his first

statement Paterson said; "I sighted my rifle at Ryan and was

about to fire when a woman walked into the line of fire and I

lifted my rifle." In his second statement Paterson said; "I

took aim at Ryan but two prison officers were in the line of fire

so I dropped my rifle again." In his third statement Paterson

said; "I took aim at Ryan and I found out I had to fire between

two prison officers to get Ryan, so I lowered my gun again."

At trial, all prison officers testified that

they did not see Hodson carrying anything, and they did not see

Hodson hit Walker. However, two witnesses Keith Dobson and his

passenger Louis Bailey testified that they saw Hodson carrying

something like an iron-bar/baton as he was chasing after Walker.

Governor Grindlay testified that he didn’t see a bar near Hodson’s

body but he found one after Hodson’s body was loaded into an

ambulance.

Apart from the inconsistencies of witnesses

evidence, missing pieces of vital evidence and no scientific

forensic evidence, the Crown relied heavily upon testimony that

Ryan had, allegedly, verbally confessed to shooting Hodson.

(Reference: Supreme Court Trial Transcript -

Queen v. Ryan & Walker, March 15-30 1966)

The Defence

The defence pointed to various substantial

discrepancies in The Crown's case. While some eyewitnesses

testified they saw Ryan to the east of Hodson when a single shot

was heard, other eyewitnesses testified Ryan was to the west of

Hodson. The discrepancies in evidence were substantial and wide-ranging.

Opas contended that each of the fourteen eyewitnesses evidence

were so contradictory that little store could be placed on them.

Philip Opas produced and human skeleton as a

visual aid to explain the trajectory of the fatal bullet, Opas

argued that the ballistics evidence indicated that the fatal

bullet entered Hodson's (shoulder) body in a downward trajectory.

He also got a Monash University mathematics professor Terry Speed,

to explain that Ryan (5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m) tall would have had

to have been 8 feet 3 inches (2.55 m) tall to have fired the shot.

These calculations were based on Ryan being twenty feet from

Hodson and Hodson was standing perfectly upright. The bullet would

enter Hodson's body 62 inches from the ground and exit 61 inches

from the ground. If the shot was in a downward angle the bullet

would have hit the road forty feet from where Hodson was hit, it

also suggested that Hodson could have been shot from another

elevated point and possibly by another prison officer. It would

cast doubt that Ryan had fired the fatal shot. But the prosecution

argued that Hodson (6 feel 1 inch (1.85 m) tall could have been

running in a stooped position, thus accounting for the bullet's

fatal downward trajectory angle of entry.

The fact that Ryan's rifle was never

scientifically tested by forensic experts was of significate

concern. Ryan intentionally kept his rifle to prove his innocence

in the event of recapture, as he knew that forensic microscopic

markings on the spent bullet would prove that it was not fired

from his rifle. Opas pointed out that the the normal course of a

person who has shot another is to dispose of the weapon, because

it is well known that guilt can be proven by scientific forensic

tests. Ballistic experts would establish the fact that the bullet

was fired by a particular rifle

The fatal bullet was a vital piece of

evidence that was never found. Scientific forensic tests on

the fatal bullet would have provided proof of who's rifle

had fired it. Although all prison-authorized rifles were the

same M1 carbine type, scientific forensic testing would

prove which rifle fired the fatal shot—every rifle leaves a

microscopic "unique marker" on the fired bullet as it

travels through the barrel of the rifle. In addition, the

spent cartridge was also, a vital missing piece of evidence.

The spent cartridge would be ejected to a distance of 5-10

feet—this meant that it was highly unlikely that Ryan's

rifle had fired a shot.

Despite extensive

search by police, neither the fatal bullet nor the spent cartridge

were ever found. At the time of recapture, Ryan had no reason to

assume the rifle he deliberately kept to prove his innocence,

would never be scientifically tested by forensic experts. Ryan had

no reason to assume the fatal bullet would never be found. Ryan

had no reason to assume the spent cartridge would never be found.

All the bullets in Ryan's M1 carbine rifle

would be accounted for if Ryan cocked the rifle with the safety-catch

on, this faulty operation (conceded by prison officer Lange,

assistant prison governor Robert Duffy, and confirmed by ballistic

experts at trial) would have caused an undischarged bullet to be

ejected, spilling onto the floor of the guard tower. Opas

established that a person who was inexperienced in handling that

type of rifle and its cocking-lever rifle, it would be easy to jam

the rifle and any attempt to clear the jam would result in a live

round being ejected.

On the eighth day of the trial Ryan was sworn

in and took the witness stand. Ryan denied firing a shot, denied

the alleged verbal (unsigned) confessions said to have been made

by him, and denied ever saying to anyone that he had shot a man.

According to Ryan, they were after the reward money by making

false allegations. "At no time did I fire a shot. My freedom

was the only objective. The rifle was taken in the first instance

so that it could not be used against me".

In his final address to the jury members, Opas

stated; "Long before this case came to trial there was most

unusual publicity given to the exploits of the accused, in the

media, on the radio and over television. It would be impossible

for anyone living in a capital city in Australia to approach this

trial without some pre-conceived notions based on what they had

read or heard about the case. It is easy to take the view of the

accused that they are convicted criminals, a perfect scapegoat a

convicted person would become if he became the target for a

trumped-up charge."

After a trial in the Victorian Supreme Court

lasting twelve sitting days the jury found Ryan guilty of murder.

Ryan was convicted of the murder of Hodson.

Justice John Starke wasted no time in passing the sentence of

death. Starke asked Ryan if he had anything to say, Ryan stated;

"I still maintain my innocence. I will consult with my counsel

with a view to appeal. That is all I have to say!" Without

further delay, without the right of plea by the defence and

without the usual adjournment prior to sentencing, Starke

sentenced Ryan to death; "Ronald Joseph Ryan, you have been

found guilty of murder of George Henry Hodson, it is the sentence

of this court that you be taken from here to the place from where

you came (Pentridge Prison) and on a day and hour to be fixed, you

shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and may God have

mercy on your soul."

(Reference: Supreme Court Trial Transcript - Queen v. Ryan &

Walker, March 15-30 1966)

After the

trial

According to juryman Tom

Gildea, the jury evidently thought that the death sentence would

be commuted, as had happened in the previous 35 death penalties

cases since 1951. Gildea's account of the discussions in the jury

room, not one member of the jury thought that Ryan would be

executed.

Of the jury, two members who thought

Ryan was not guilty but were convinced by the others to bring in a

guilty verdict. They were so sure that the death sentence would be

commuted to life imprisonment, that they did not even discuss the

issue of making a recommendation for mercy along with their guilty

verdict.

Later, some of the jurors came forth and stated

they would never have convicted Ryan of murder had they known that

he would in fact be executed. Seven jury members signed separate

petitions requesting Ryan's death sentence be commuted to life in

prison.

Appeal

Opas, convinced of

Ryan's innocence, decided to appeal against the murder verdict.

The first appeal was to the Victorian Court of

Criminal Appeal, a bench consisting of three judges of the Supreme

Court. His ground was that the verdict was against the weight of

the evidence. He argued that as a matter of law that the inherent

inconsistencies and improbabilities and even impossibilities in

the evidence. The appeal was dismissed on June 8, 1966. In October

1966, a second appeal is rejected. Two months later after a state

government cabinet meeting Premier Bolte announces that Ryan's

death sentence will not be commuted. Ryan was scheduled to hang on

January 9, 1966.

Ryan had a right to increased free legal

assistance for expert forensics analysis, to hire expert witnesses,

and to present a series of appeals and recourses that were

available to those facing execution by the government. The Full

Court agreed that it was unthinkable that a man should be executed

before he had exhausted his ultimate right of appeals. Opas

decides to apply to the Privy Council in London. The appeal is a

vestigial remnant of an appeal to the sovereign in person. The

Privy Council gives an opinion always ending with; "and we

shall so humbly advise Her Majesty" on the decision of whether

the appeal has been allowed or dismissed.

With all legal avenues yet to be

exhausted, legal aid to Ryan was cut by the Bolte Government.

Premier Bolte then directed the Public Solicitor to withdraw

Opas' brief as the government was not going to fund the

petition to the Privy Council.Premier Bolte then directed

the Public Solicitor to withdraw Opas' brief as the

government was not going to fund the petition to the Privy

Council.

Opas, convinced of Ryan's

innocence, agreed to work without pay. Opas consulted the Ethics

Committee of the Bar Council to seek approval to make a public

appeal for a solicitor prepared to brief him, as Opas was prepared

to pay his travel, other expenses and appear without fee. The

Committee said that this would be touting for business and was

unethical. Opas argued that a man’s life was at stake and he could

not see how he would be touting when no payment was involved. Opas

defied the ruling and on national radio sought an instructor. Opas

was inundated with offers and accepted the first application,

being from Ralph Freadman. Alleyne Kiddle was in London completing

a Master’s degree and she agreed to take a junior brief at a fee

of two-thirds of nothing.

Opas then flew to

London to present Ryan's case to the highest judges in the

Commonwealth. Ryan's execution was reluctantly delayed by Premier

Bolte awaiting the Privy Council's decision. However, Bolte took

no chance of the possible that Her Majesty might give a decision

contrary to the advice of the Judicial Committee. Bolte schedules

Ryan's execution on the morning of Friday February 3, 1967. The

decision of Her Majesty in the Privy Council to refuse leave to

appeal was announced on February 10, 1967 (seven days after Ryan

was executed).

A Political

Hanging

Henry Bolte, Victoria’s

longest serving State Premier, was a key figure in the hanging of

Ronald Ryan. Until this time, the State Government of Victoria had

commuted every death sentence passed since 1951, after three

people Robert Clayton, Norman Andrews and Jean Lee (the last

female executed in Australia) had been executed for the tortured

murder of an old man.

At the time of the Ryan

sentence there were at least four State cabinet members who

opposed capital punishment but Premier Bolte was determined to

prevail.

Bolte wanted take the "tough on crime"

stance. Justice John Starke reported that Bolte had insisted that

the death sentence be carried out. Bolte's determination to hang

Ryan to boost his votes is widely documented.

When it became apparent that the Premier Mr (later Sir Henry)

Bolte intended to proceed with the execution, a secret eleventh-hour

plea for mercy was made by four jury members who had found Ryan

guilty of murder. They sent petitioning letters to the Victorian

governor, stating that in reaching their verdict, they had

believed that capital punishment had been abolished in Victoria

and requesting that the Governor exercise the Royal Prerogative of

Mercy and commute Ryan's sentence of death.

Bolte denied all requests for mercy and was

determined Ryan would hang. The approaching execution of Ryan

prompted widespread protests in Victoria and elsewhere around the

country.

Newspapers in Melbourne, traditionally

supporters of the Bolte government, deserted him on the issue and

ran a campaign of spirited opposition on the grounds that the

death penalty was barbaric. There is some evidence that, for

premier Bolte, Ryan's execution was an opportunity for him to re-assert

his political authority.

As Ryan's execution approached, his 75-year old

mother made a final plea to Premier Bolte for mercy. Cecilia Ryan

wrote: "I plead at this late hour you will reverse your

decision to hang my son. If you cannot find it in your heart to

grant this request then I pray you will grant me one last favour,

that the body of my son be given into my custody after his death

so that I can give him a Christian burial. I pray to God for the

success of this last prayer". Premier Bolte promptly replied

in a letter, saying that her son would not be spared the death

penalty and that law required his body be buried within prison

grounds. It would not be returned to her for a Christian burial.

Churches, universities, unions and a large

number of the public and legal professions opposed the death

sentence. An estimated 18,000 people participated in street

protests and 15,000 signed a petition against the hanging.

Melbourne newspapers The Age, The Herald and The Sun, ran

campaigns opposing the hanging of Ryan. The Australian

Broadcasting Commission (ABC) suspended radio broadcasts for two

minutes as a protest.

Eve of

Ryan's Execution

On the afternoon of the eve of Ryan's

hanging, Dr opas appeared before the trial judge Justice

John Starke. Opas was seeking a postponement of the

execution, due to the opportunity of testing new proferred

evidence. Opas pleaded with Starke, and said; "Why the

indecent haste to hang this man until we have tested all

possible exculpatory evidence?" But Starke rejected the

application.

The Attorney-General Arthur

Rylah, rejected a second plea to refer Ryan's case to the Full

Court under Section 584 of the Crimes Act. A third attempt to save

Ryan in the form of a petition presented at the Crown Solicitor's

office pleading for clemency, was also rejected. Close secrecy

surrounded all Government moves on the Ryan case.

That evening, a former Pentridge prisoner Allan

John Cane, arrived in Melbourne from Brisbane in a new bid to save

Ryan. An affidavit by Cane, which was presented to Cabinet, says

he and seven prisoners were outside the cookhouse, when they saw

and heard a prison warder fire a shot from the No. 1 guard post at

Pentridge Prison, on the day Hodson was shot. Police had

interviewed these prisoners but none were called on at the trial

to give evidence. Cane was immediately rushed into conference with

his solicitor Bernard Gaynor, who tried to contact Cabinet

Ministers informing them of Can's arrival. Gaynor telephoned

Government House seeking an audience with The Governor Sir Rohan

Delacombe. However, Gaynor was told by a Government House

spokesman that nobody would be answering calls until 9 am in the

morning (one hour after Ryan's scheduled execution.) Gaynor said

Cane's mission had failed.

At 11 pm, Ryan was informed that his final

petition for mercy had been rejected. More than 3,000 people

gathered outside Pentridge Prison in protest to the hanging.

Shortly before midnight more than 200 police were at the prison to

control the demonstrators. For a moment the crowd looked as if it

might break through the barricades police had erected. Extra

police rushed to the prison in three buses to help control the

noisy demonstrators. The great majority of demonstrators were non-violent

and chanted "Don't hang Ryan" sporadically between

listening to impromptu anti-hanging speeches. These were greeted

with enthusiastic cheering and applause and more chanting.

Placards read; "Don't Hang a Man Who Could be Innocent."

Ryan's Final Hours and Last Letters

The night prior to the execution, Ryan was transferred to a cell,

just a few steps away from the gallows trapdoor. Father Brosnan

was with Ryan most of this time. In the eleventh-hour Ryan wrote

his last letters to members of his family, his defence attorney,

The Anti-Hanging Committee and Father Brosnan. The letters were

handwritten on toilet paper inside his cell and neatly folded. In

the documentary film The Last Man Hanged Ryan's letter to

The Anti-Hanging Committee is read out loud. Ryan wrote; " ...

I state most emphatically that I am not guilty of murder."

Execution

Ryan was hanged in 'D' Division at Pentridge Prison at 8:00 am on

Friday 3 February, 1967.

For unknown reasons, Ryan was not given the

right to make a final verbal statement to the people who had

gathered to witness his execution.

Ryan refused to have any sedatives but he did

have a nip of whisky, and walked calmly onto the gallows trapdoor.

Ryan's last words were to the hangman; "God bless you, please

make it quick." The hangman wasted no time after adjusting the

noose, quickly leapt to pulled the lever. Ryan fell through the

trapdoor with a loud crash.

A nationwide three-minute silence was observed

at the exact time that Ryan was hanged. Thousands of people

protesting outside the prison knew the moment of the execution

because the pigeons on the D Division roof all took flight.

Later that day, Ryan's body was buried in an

unmarked grave within the "D" Division prison facility. Three bags

of quicklime was spread over the coffin. The exact location of

Ryan's grave has never been released by the authorities.

A media reporter asked Bolte what he was doing

at 8:00 am. Bolte replied; "One of the three S’s I suppose"”

when asked what he meant by that, Bolte replied; "A shit, a

shave or a shower!".

While the biggest public protest ever seen in

the history of Australia was not successful in averting Ryan’s

execution, the protest campaign to save Ryan from the gallows

ensured that governments around Australia regarded it as too

difficult politically to ever enforce the death penalty again.

Within twenty years, capital punishment would be abolished

federally and in all state and territory jurisdictions. In 1985,

Australia officially abolished capital punishment.

Today, almost all federal and state politicians from all political

parties are opposed to the reintroduction of capital punishment in

Australia, for all crimes. Whether these politicians are

representative of their voters is less clear. In recent years,

Australian politicians (both government and opposition) have made

various comments that have changed Australia's opposition to the

death penalty. The implications of this shift in Australian policy

have not yet been fully explored or debated.

Nineteen Years

Later

Nineteen years after Ryan's

execution, a prison officer Doug Pascoe, confessed on-air to

Channel 9 and the media, that he fired a shot during Ryan's escape

bid. The former prison guard wept on Channel 7 'Day By Day'

program claiming his shot may have accidentally killed his fellow

prison guard, George Hodson. Pascoe said he had not been

interviewed after the shooting.

On 12the June 1986, Pascoe tried to tell his

story to the media because of his involvement with the church.

Pascoe said he had not told anyone that he fired a shot during the

escape because at that time, "I was a 23-year-old coward". Pascoe

said he did not know why he fired except for the hype of the

moment. News of Pascoe's claims were met with mixed reaction from

lawyers, prison guards, and others directly involved in the Ryan

case. His claim was rejected by authorities, including former

prison warder Bill Newman who said Pascoe could not have fired a

shot. The trial judge who sentenced Ryan to death declined to make

a comment.

After the claims and counter-claims, Dr Opas

said only a "proper enquiry" would determine the truth. Public

solicitor Allan Douglas, said Ronald Ryan should not have been

convicted, let alone hanged, on the evidence presented to the

court. Douglas said Ryan did not get a fair hearing at trial

because of adverse media reports. He added that the actions of the

Bolte Government had been "pretty drastic". Senior law lecturer at

Melbourne University Ian Elliott, said the claims by Pascoe might

form the basis of corroborative evidence for material at Ryan's

trial. A public witness at Ryan's hanging was journalist Patrick

Tennison, who said it was incumbent on the Government to explore

fully the circumstances of Ryan's hanging and to determine the

veracity of Pascoe's claims.

Forty Years Later

Forty years after Ronald Ryan was hanged, his family members made

a request to have his body exhumed and placed with his late wife

Dorothy, at Portland Cemetery. Victorian Premier John Brumby, gave

permission for archaeological work and exhumation of Ryan's body.

Only recently has it been revealed by

undertakers John Roy V. Allison that Ryan was buried in a highly

polished darkwood coffin with the best trimmings, high-quality

handles, satin lining, and a crucifix attached to the coffin. In a

protest against the hanging, the undertakers added the best of

everything to Ryan's coffin, so that his daughters would know he

had a bit of dignity.

However, the daughter of murdered prison guard,

Carole Hodson-Barnes-Hodson-Price, strongly objected and claimed

Ryan did not deserve to be buried in consecrated ground. She was a

13-year-old at the time of her father's death and had not lived

with her father for a number of years. When visiting Ryan's

unmarked grave recently, she danced and jumped on it

Carole Hodson angrily demanded to know who was funding Ryan's

exhumation and made a plea to Victorian Premier John Brumby to

ensure Ryan's remains not be removed from the prison grounds and

not be returned to Ryan's family members. But Mr Brumby supported

the views of Ryan's relatives to have his body exhumed so it could

be cremated and placed with his late wife Dorothy, buried at

Portland Cemetery.

Carole Hodson has been unable

to bury the bitterness and get any sense of peace after so many

years. She has been vocal and angry and doesn't believe Ryan

deserves any consideration. Her request to the journalist for

media interview has been ignored.

Carole

Hodson has met Ryan's family members, where she has consistently

gate-crashed various Ryan memorials and documentary film openings

to loudly protest. Ryan's daughter Wendy, has told how Carole

Hodson's cruel and unneccesary actions continue to add extra

emotional pain for the entire innocent family members, who believe

their loved one was wrongly convicted and hanged an innocent man.

The effects of the death penalty experienced by

families of executed criminals are documented in two books; Hidden

Victims: The Effects of the Death Penalty on Families of the

Accused by Susan F. Sharp (Associate Professor of Sociology) and

Capital Consequences: Families of The Condemned by Rachel King (Lawyer).

The books highlight the death penalty's hidden victims - the

families of executed offenders and how the execution trickles down

to those closely connected to the offender. Family members and

friends experience a profoundly complicated and socially isolating

grief process - economic, social and psychological repercussions

that shape the lives of the forgotten families of executed

offenders. Post-traumatic stress disorder can also affect these

innocent family members.

The family members of Ronald Ryan - the unseen

and unheard innocent victims of Ryan's execution, They have been

devastated and have suffered in silence without sympathy or

comfort, having had a ripple effect through to the future

generations. The Ryan family have kept a low-profile over the

decades, but have endured public scrutiny, been subjected to

harassment, have had to endure the after-math false allegations

and are struggling to live with the knowledge that Ryan may have

been innocent of murder when he was executed by the State of

Victoria. The emotional pain of Ryan's family members tends to

attract less attention and empathy from the media and the public,

than that of the victim's family members.

The Case for

Innocence

Australian Criminologist

Professor Gordon Hawkins, at Sydney University Law School doubts

the validity of the unsigned confessions of Ryan in a television

film documentary, Beyond Reasonable Doubt. Although verbal

confessions are not permissible in court, in the 1960s the public

and therefore the jury, were much more trusting of the police.

Whether as a result, an innocent man was hanged there is at least

a reasonable doubt. Professor Hawkins questions why Ronald Ryan, a

seasoned criminal, would suddenly feel the need to tell all to the

police? Was he 'verballed’ as such unsigned confessions are called?

These days 'verbals’ are virtually impossible as police have to

record all interviews they carry out in connection with a crime,

following extraordinary revelations of police corruption uncovered

by various police royal commissions.

Evidence

pointing to the innocence of Ronald Ryan may have been lost when

prison guard Helmut Lange, committed suicide by shooting himself

in the head whilst on duty at Pentridge Prison, two years after

Ryan was hanged. It is alleged that a close friend of Lange (who

wanted to remain anonymous) claimed Lange had been troubled since

Ryan's hanging and committed suicide.

This

anonymous friend of Lange, telephoned Ryan's defence attorney Dr

Philip Opas QC, years after Lange's death to claim that Lange

confessed to finding the missing bullet casing in the prison guard

tower and told his friend he had made an official report to prison

authorities at the time, attaching the missing bullet casing.

But Lange had been ordered by "someone" to make a new

statement, excluding any reference to the missing bullet casing.

Fearing for his job, Lange made a new statement. At trial, Lange

testified that he did not see a bullet casing. Dr Opas advised the

caller to inform the Police but it is unknown whether in fact the

caller did. Police refused to comment.

In 1993,

a former Pentridge prisoner Harold Sheehan claimed he had

witnessed the shooting but had not come forward at the time.

Sheehan saw Ryan on his knees when the shot rang out and therefore,

Ryan could not have inflicted the wound that passed in a downward

trajectory angle that killed Hodson.

All prison

authorized M1 carbine rifles were issued with eight rounds of

bullets, including the rifle seized by Ryan from Lange. Seven of

the eight rounds were accounted for. If the eighth fell on the

floor of the prison watch tower when Ryan cocked the rifle with

the safety catch on, thereby ejecting a live round, then the

bullet that killed Hodson must have been fired by a person other

than Ryan.

In a letter, Opas on Ryan - The

Innocence of Ronald Ryan written to The Victorian Bar

Association and published in The Bar News in Spring 2002, Dr Opas

responded to assertions made by Julian Burnside (who was reviewing

Mike Richard's book The Hanged Man,) that Ryan was guilty,

the verdict was correct but the punishment was wrong. In addition,

the editors of The Victorian Criminal Bar Association disagreed

with Julian Burnside personal assertion of Ryan's guilt.

Dr Opas vehemently disagrees with this assertion and refuses to

believe that at any time did Ryan confess to anyone that he fired

a shot. Burnside (a human rights advocate) has been asked on

several occasions to explain how came to his assertion, but has

refused to explain. Dr Opas vehemently states that there is no

evidence anywhere, that Ryan ever confessed guilt to anyone,

either verbally or in writing.

Ryan gave

evidence and swore that he did not fire at Hodson. He denied

firing a shot at all. Ryan denied the alleged verbal confessions

said to have been made by him. Dr Opas says the last words Ryan

said to him were; We’ve all got to go sometime, but I don’t

want to go this way for something I didn't do.

On 1 March 2004, in an interview with the Australian Coalition

Against Death Penalty (ACADP) Dr Opas said; I want to put the

record straight. I want the truth told about Ronald Ryan - that an

innocent man went to the gallows. I want the truth to be made

available to everyone, for anyone young and old, who may want to

do research into Ryan's case or research on the issue of capital

punishment. I will go to my grave firmly of the opinion that

Ronald Ryan did not commit murder. I refuse to believe that at any

time he told anyone that he did.

On 23

August 2008, Dr Philip Opas QC, OBE died after a long illness at

the age of 91. Opas maintained Ryan's innocence to the end. He was

posthumously awarded an AM : Australia Day Honours in February

2009.

Mr. Justice Starke the judge at Ryan's

trial, and a committed abolitionist was convinced of Ryan's guilt

but did not agree Ryan should hang. Until his death in 1992,

Starke remained troubled about Ryan's hanging and would often ask

his colleagues if they thought he did the right thing.

The Facts Supporting Innocence

-

Ryan's rifle was never scientifically tested by

forensic experts.

There was no proof that Ryan's

rifle had been fired.

The fatal bullet that

passed through Hodson's body was never found despite extensive

search by police.

The spent cartridge, also, was

never found despite extensive search by police. If Ryan had fired

a shot, a spent cartridge would have spilt on the ground.

It was never proven that the fatal bullet came from the weapon in

Ryan's possession.

All fourteen witnesses testified they

heard one single shot.

Paterson admitted and testified he fired

one single shot.

No person heard two shots fired. If Ryan

had also fired a shot, at least one person would have heard two

shots. Only one shot was heard.

Ballistic evidence indicated that Hodson

was shot in a downward trajectory angle.

The measurement of the entry and exit

wound on Hodson's body indicated that the shot was fired from an

elevated position.

Ryan (a shorter man) could not have fired

at Hodson (a taller man) in such a downward trajectory angle, as

both were on level ground.

Two eyewitnesses testified seeing Ryan

recoil his rifle and two eyewitnesses testified seeing smoke

coming from the barrel of Ryan's rifle. In fact, at trial a

ballistic expert on firearms testified that type of rifle had no

recoil and it contained smokeless cartridges.

<Referenced Documentaries: The Last Man

Hanged, The Last of The Ryans, Beyond Reasonable Doubt, Odd Man

Out.>

Prison Chaplain Convinced Ryan Was Innocent

On 26 March 2003, Father Brosnan was interviewed by The Australian

Broadcasting Commission National Radio, Brosnan was often asked by

ther media about Ronald Ryan -- who it was believed fired the

fatal shot during the prison breakout. Just months before Brosnan

died, he said on ABC National Radio; "No I won't make a hero

out of him. He caused a situation, I don't know whose bullet

killed who, but a friend of mine died. But I'll tell you what, he

had heroic qualities."

Father John Brosnan

was a Catholic priest for 57 years. For 30 years he was Pentridge

Prison chaplain. He had come to know Ryan very well and

accompanied Ryan to the gallows. In February 2007, The Catholic

Archdiocese published a story that Father Brosnan was convinced

and always believed Ryan was innocent.

Documentaries on Ronald Joseph Ryan

There are various educational documentary films/stories on Ronald

Ryan. They are dramatised documentaries, based on research with a

mixture of re-creating interviews with the people directly

involved in the Ryan case. The documentaries include archival

material depicting the life and death of Ronald Joseph Ryan, the

events surrounding the shooting, the case, lack of scientific

evidence, missing pieces of vital evidence, witnesses

inconsistencies at trial, and the political power leading up to

the hanging of Ryan. The documentaries have candid interviews with

the people who knew Ryan well - his wife, lawyer, fellow escapee,

trial judge, the catholic priest, politicians and journalists who

witnessed Ryan's execution. These documentaries tell the true

story of Ronald Joseph Ryan, a petty-thief with no police record

of violence, whose botched escape from Pentridge Prison resulted

in a political execution.

Film and Television Documentaries

-

The Last Man Hanged, historical

documentary, ABC, Australia, 1993

-

The Last Of The Ryans, television

movie, Crawford Productions, Australia, 23 April 1997 (Winner of

The 1998 Award of Distinction Telefeatures, TV Drama & Mini

Series)

-

Beyond Reasonable Doubt - The Case of

Ronald Ryan, documentary series, 1977 Australian Film

Commission

-

Odd Man Out - The Story of Ronald Ryan

Three-part television mini-series

-

Who Hung Ronald Ryan? Australian

Broadcasting Corporation Film (A Documentary Film on The

Execution of Ronald Ryan - released 1987)