|

In the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas

AP-74,524

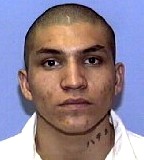

Jorge

Alfredo Salinas, Appellant

v.

The State of Texas

ON DIRECT APPEAL

CAUSE NO. CR-3043-01-G IN THE 370th

DISTRICT COURT

HIDALGO COUNTY

Meyers, J.,

delivered the opinion of the Court in which Keller,

P.J., and Price, Johnson, Hervey,

Holcomb, and Cochran, JJ., joined.

Womack and Keasler, JJ.,

concurred.

Appellant was convicted in August 2002 of capital murder. Tex.

Penal Code Ann. � 19.03(a). Pursuant to the jury's answers to

the special issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure

Article 37.071, sections 2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge

sentenced appellant to death. Art. 37.071 � 2(g).

(1) Direct

appeal to this Court is automatic. Art. 37.071 � 2(h). Appellant

raises six points of error. We reform appellant's death sentence

to a sentence of life imprisonment, and otherwise affirm.

In point

of error two, appellant claims the evidence is legally

insufficient to establish a specific intent to kill. In

determining the sufficiency of the evidence, the evidence is

viewed in the light most favorable to the verdict to decide

whether any rational trier of fact could have found the

essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.

Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979).

Appellant,

his brother Lorenzo, and Oscar Villa Sevilla were at appellant's

house in Mission on the night of Saturday, July 28, 2001,

smoking marijuana. Sevilla stated that he wanted to get a gun

and steal a car.

Appellant

said, "Let's see if you have the balls; let's go." Appellant

retrieved a shotgun that he had previously stolen and gave it to

Sevilla. Appellant and Sevilla walked to a nearby intersection.

Sevilla jumped out and pointed the shotgun at the first car to

stop at the four-way stop. Geronimo Morales was driving the car,

and his 21-month-old child, Leslie Ann Morales, was in her car

seat in the back.

Sevilla

pounded on the window, and Morales opened the door. Sevilla got

into the driver's seat and forced Morales over to the

passenger's seat. Sevilla handed appellant the gun, and

appellant pointed it at Morales. Morales cried and pleaded with

them not to hurt the baby. Appellant got into the back seat of

the car while still pointing the gun at Morales.

Sevilla

grabbed Morales by the hair and began hitting him. Sevilla asked

Morales for his money, but Morales stated that he did not have

any. This made Sevilla angry, and he beat Morales some more.

Sevilla stopped the car, retrieved the gun from appellant, and

dragged Morales into some orchards and shot him. He stole

Morales' wallet, a gold ring, and a silver necklace with a skull

on it.

Sevilla returned to the car, and appellant suggested that they

return to his house and pick up his brother Lorenzo. When

Lorenzo got into the car, he asked them what they were going to

do with the baby. Lorenzo suggested that they leave her at a

store or someplace where someone would find her, but Sevilla

said they were going to dump her where no one would find her.

They drove to an area south of town about a half a mile from the

Rio Grande River, and close to La Lomita Mission. Appellant and

Lorenzo

(2) took the

baby out of the car, still in her car seat, and placed her in

some tall grass.

The three

then drove Morales' car to Maria Alma Rosa Acevedo Pineda's

house in Reynosa, Mexico, arriving between 10:30 and 11:00 p.m.

on July 28, 2001. Pineda's husband was a first cousin to

appellant and Lorenzo. Appellant initially told Pineda that the

car belonged to Sevilla. Lorenzo gave Pineda's son a silver

necklace with a skull on it, which was later identified as

Morales' necklace.

Later that

night, appellant told Pineda that he had something he wanted to

tell her, but he was afraid she would tell someone else. He then

told her that they had "broken some guy," but Pineda did not

believe him. Pineda stated that the phrase "broken some guy"

means "to kill, to break, to shoot some person."

The three

cohorts tried to sell Morales' car in Reynosa, but were

unsuccessful. On Sunday, July 29, Reynosa police attempted to

stop them while they were driving Morales' car. A chase ensued,

and they abandoned the vehicle. Reynosa police seized the car

and turned it over to authorities in the United States. The

three cohorts returned to the United States on Monday after

selling the shotgun. Appellant told his girlfriend about what

they had done and took her to see Morales' body where they had

left it.

Leslie

Ann's body was found by border patrol officers around 7 p.m. on

July 29, 2001. The officers were patrolling south of La Lomita

Mission near the river, looking for illegal aliens who might be

hiding in the grass. The patrol officer who testified stated

that the child was in an area where she was not likely to be

found. Other testimony placed her approximately fifteen feet

from the road in grass that was two to three feet high. The

medical examiner testified that Leslie Ann died from dehydration,

exposure to the elements, and heatstroke.

Morales'

body was found on August 1, 2001. He died from a gunshot wound

at close range to the right side of the head.

Appellant

argues that the evidence does not support a finding that he had

a specific intent to kill anyone or to assist, promote, or

encourage Sevilla in committing the murders. He contends, "The

only thing he intended to do, and agreed with, was to steal a

car at gun point." He claims Sevilla alone formulated, during

the course of the robbery, the specific intent to kill the

victims.

Appellant

says the murders, at least on appellant's part, were unintended,

unplanned and random, spurred only by his co-hort's independent

impulse. He claims he could not have reasonably foreseen or

anticipated Sevilla's actions when they stole the car.

The

indictment charged appellant with capital murder in three

separate counts. The first count charged him with the murder of

Morales while in the course of committing or attempting to

commit robbery of him. The charge required the jury to find that

(1) appellant intentionally caused Morales' death while in the

course of robbing him; or (2) either Lorenzo or Sevilla had done

so, under circumstances rendering appellant responsible under

the law of parties.

The second

count charged appellant with committing the murders of Morales

and Leslie Ann in the same criminal transaction. The charge

required the jury to find that (1) appellant intentionally or

knowingly caused their deaths; or (2) either Lorenzo or Sevilla

had intentionally or knowingly caused their deaths, under

circumstances rendering appellant responsible under the law of

parties, or because the murders were the anticipated result of a

conspiracy to commit another offense (robbery). Appellant was

charged in the third count with the murder of Leslie Ann, an

individual younger than six years of age. The jury charge

required the jury to find that (1) appellant intentionally or

knowingly caused the death of Leslie Ann; or (2) either Lorenzo

or Sevilla had intentionally or knowingly caused her death,

under circumstances rendering appellant responsible under the

law of parties, or because the murder was the anticipated result

of a conspiracy to commit another offense (robbery).

The court

submitted a separate jury charge for each count, along with a

separate verdict sheet for each count. The jury found appellant

guilty of each count. Appellant does not argue his insufficiency

claim specifically as to any one or more of the counts.

Appellant's claim that the evidence does not support a finding

that he had specific intent to kill is applicable only to count

one because that is the only theory under which intentionally

causing death is an element. His conviction could be supported

under counts two and three upon a finding that he acted

intentionally or knowingly. Because the jury found

appellant guilty under each of the three theories separately,

two of which do not require a finding that applicant acted

intentionally, appellant's argument regarding legal

insufficiency to prove specific intent is moot.

In a

conclusory statement, appellant also claims that the evidence is

insufficient to support a finding that appellant assisted,

promoted, or encouraged Sevilla in committing the murders. He

further asserts that he could not have reasonably foreseen or

anticipated Sevilla's actions in killing the victims. We address

these contentions in the interest of justice.

"Evidence

is sufficient to convict under the law of parties where the

defendant is physically present at the commission of the offense

and encourages its commission by words or other agreement."

Ransom v. State, 920 S.W.2d 288, 302 (Tex. Crim. App.

1994). Party participation may be shown by events occurring

before, during, and after the commission of the offense, and may

be demonstrated by actions showing an understanding and common

design to do the prohibited act. Id.

According

to appellant's own confession, when Sevilla stated that he

wanted to commit a carjacking, appellant dared him to do it and

provided him with a shotgun. Sevilla's intent to do more than

steal the car was apparent. If Sevilla had intended only to

steal the car, he could have ordered Morales and Leslie Ann out

as soon as he stopped the car, and left them at the side of the

road.

Instead,

Sevilla handed the shotgun to appellant, who pointed it at

Morales as Sevilla got in and drove to a remote area. Appellant

did nothing as he watched Sevilla drag Morales from the car and

shoot him. Later, Sevilla stated his plan to leave Leslie Ann

where she could not be found, rejecting Lorenzo's suggestion to

leave her in a public place where she could be found.

The

evidence supports the inference that appellant and Lorenzo

removed Leslie Ann from the car, still strapped in her car seat,

and placed her in tall grass fifteen feet from a road and

outside of town. The evidence is sufficient to support a finding

that appellant encouraged and participated in, as a party, the

murders of Morales and Leslie Ann. Point of error two is

overruled.

In his

first point of error, appellant claims that he was denied the

effective assistance of counsel at trial for several reasons. To

establish ineffective assistance of counsel, appellant must show

by a preponderance of the evidence that his counsel's

representation fell below the standard of prevailing

professional norms, and that there is a reasonable probability

that, but for counsel's deficiency, the result of the trial

would have been different. Strickland v. Washington,

466 U.S. 668 (1984); Mallett v. State, 65 S.W.3d 59,

62-63 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001).

Review of

counsel's representation is highly deferential, and the

reviewing court indulges a strong presumption that counsel's

conduct fell within a wide range of reasonable representation.

Mallett, 65 S.W.3d at 63. A reviewing court will rarely

be in a position on direct appeal to fairly evaluate the merits

of an ineffective assistance claim. Thompson v. State,

9 S.W.3d 808, 813-14 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999). "In the majority of

cases, the record on direct appeal is undeveloped and cannot

adequately reflect the motives behind trial counsel's actions."

Mallett, 65 S.W.3d at 63. To overcome the presumption

of reasonable professional assistance, "any allegation of

ineffectiveness must be firmly founded in the record, and the

record must affirmatively demonstrate the alleged

ineffectiveness." Thompson, 9 S.W.2d at 813 (citing

McFarland v. State, 928 S.W.2d 482, 500 (Tex. Crim. App.

1996)).

Appellant

alleges that his trial counsel was ineffective because he did

not file a motion to transfer venue. Appellant claims he told

his counsel that he wanted a change of venue, and that he was

prepared to file his own affidavit and the affidavits of two

other compurgators stating that the media coverage was incessant

and the community sentiment was overwhelmingly negative and

antagonistic toward appellant. Appellant points to nothing in

the record in support of his allegations.

In the

absence of anything in the record affirmatively demonstrating

otherwise, we presume that his counsel made a reasonable and

strategic decision not to ask for a change of venue. See

Mallet, 65 S.W.3d at 63.

Appellant

also contends that his trial counsel was ineffective for failing

to allow appellant to testify on his own behalf at the guilt

phase of the trial. Appellant claims his counsel advised against

testifying due to appellant's prior convictions, but appellant

remained adamant about wanting to testify. "Every criminal

defendant is privileged to testify in his own defense, or to

refuse to do so." Harris v. New York, 401 U.S. 222, 225

(1971); see also Maddox v. State, 613 S.W.2d

275, 280 (Tex. Crim. App. 1980)(recognizing that attorney has

duty to protect client's right to testify). However, appellant's

assertions in his brief on appeal, in the absence of anything in

the trial record, are insufficient to show that he asserted his

right to testify and his attorney failed to protect it.

Mallett, 65 S.W.3d at 63.

Appellant next contends that his trial counsel was ineffective

for failing to file a motion to quash the indictment or request

a severance. Appellant claims that his indictment charged him

with three separate and distinct capital murders,

(3) and

contends that trial counsel should have recognized the

indictment as "defective, misjoined, or subject to a severance."

He complains that trial counsel should have filed a motion to

quash, a motion for election, or a motion for severance.

Trial counsel did file a Motion to Quash and/or Sever in which

he complained of the three-count indictment and requested a

severance of the charges. In the alternative, counsel asked that

the indictment be quashed. Finally, he asked that the State be

required to elect the charge on which it would proceed. The

motion was addressed in a pretrial hearing. Appellant's counsel

did everything appellant contends he should have.

(4)

Finally,

appellant claims that his trial counsel was ineffective for

failing to request an instruction on the lesser-included offense

of felony murder in the court's charge at the guilt phase of the

trial. Although appellant's attorney requested and received a

charge on the lesser-included offense of murder, appellant

argues that a charge on felony murder would have been more

appropriate.

A charge

on a lesser-included offense should be given when (1) the lesser-included

offense is included within the proof necessary to establish the

offense charged; and (2) there is some evidence that would

permit a rational jury to find that the defendant is guilty of

the lesser offense but not guilty of the greater. See,

Rousseau v. State, 855 S.W.2d 666, 672-73 (Tex. Crim. App.

1993); Feldman v. State, 71 S.W.3d 738, 750-51

(Tex. Crim. App. 2002).

In meeting

the second prong, there must be some evidence from which a

rational jury could acquit the defendant of the greater offense

while convicting him of the lesser-included offense. Feldman,

71 S.W.3d at 750. Felony murder is a lesser-included offense of

capital murder. Rousseau, 855 S.W.2d at 673. Culpable

mental state is the only difference between the two offenses.

"Capital murder requires the existence of an 'intentional cause

of death,' . . . while in felony murder, 'the culpable mental

state for the act of murder is supplied by the mental state

accompanying the underlying ... felony....'" Id. (quoting

Rodriguez v. State, 548 S.W.2d 26, 29 (Tex. Crim. App.1977)).

The second prong of the test is not satisfied here, however,

because the evidence did not raise any issue of felony murder.

Appellant contends his counsel could have reasonably argued that

the evidence showed felony murder - that in the course of

committing a felony (robbery or kidnapping), and in furtherance

of that particular felony, appellant committed an act clearly

dangerous to human life that resulted in the death of an

individual.

The critical question is whether the evidence showed that

appellant (as a principal or a party) had the intent only to rob

or to kidnap, and he did not have the intent to kill. See

Santana v. State, 714 S.W.2d 1, 9 (Tex. Crim. App. 1986).

Dragging Morales from the car and shooting him in the head with

a shotgun at close range were not merely acts clearly dangerous

to human life that resulted in a death. Likewise, placing Leslie

Ann, a 21-month-old child, strapped into her car seat, in tall

grass fifteen feet from a road and outside of town, was not

merely an act clearly dangerous to human life.

Whether appellant was the actual actor or criminally responsible

for the acts of his cohorts by virtue of the law of parties, the

evidence shows not only an intent to commit robbery or

a lesser included offense, but also the intent to kill.

Thus the evidence did not raise the issue of felony murder.

Appellant was not entitled to a charge on the lesser-included

offense of felony murder and therefore his counsel was not

ineffective when he did not request one. Point of error one is

overruled.

(5)

In his

fifth point of error, appellant claims that the trial court

erred in denying his motion to impose reasonable restrictions on

the media's coverage of pretrial hearings. He contends that such

coverage might have tainted the jury pool.

In a written motion entitled Motion to Restrict Publicity,

appellant requested that all pretrial hearings be held in

chambers, outside the presence and hearing of the public and

press. At a pretrial hearing addressing the motion, appellant

stated that he wanted to restrict the media's coverage of

pretrial hearings so that witnesses who would later be placed

under "the Rule"

(6) during

trial would not have access to certain information or testimony

via news reports on pretrial hearings. As an "alternative

solution," appellant suggested admonishing the witnesses, like

the jury, that they were not to read the paper or watch

television.

The court stated that it was not inclined to limit the media as

broadly as stated in appellant's written motion, but agreed that

a witness admonishment like that suggested by appellant at the

hearing "may be a good practice." The court stated that it would

consider the option, but was not ready to rule on it at that

time. The court asked that appellant bring it to his attention

later, before the Rule was invoked. Appellant does not point to

any place in the record where he ultimately obtained a ruling on

the issue. In stating that he was willing to accept an

alternative solution to his complaint about media reports on

pretrial hearings, appellant therefore waived the complaint as

raised in his written motion. Further, in failing to obtain a

ruling on his proposed alternative solution, he failed to

preserve that issue for review.

(7) Tex. R.

App. P. 33.1. Point of error five is overruled.

In his

sixth point of error, appellant contends that because he was

seventeen years old when the crime was committed, assessment of

the death penalty against him violates the Eighth Amendment to

the United States Constitution. In support of this claim,

appellant cites State ex rel. Simmons v. Roper, 112 S.W.3d

397 (Mo. 2003), in which the United States Supreme Court granted

certiorari to reconsider whether the Eighth Amendment is

violated by the imposition of the death penalty against a

criminal defendant who was seventeen years old when he committed

the capital crime.

The United

States Supreme Court has since decided Roper v. Simmons,

544 U.S.___, 125 S.Ct. 1183, 161 L.Ed.2d 1. The Court has now

held that the "Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbid

imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were under the

age of 18 when their crimes were committed." 125 S.Ct. at 1200,

161 L.Ed.2d at 28.

There is

evidence in the record that appellant was seventeen years old

when he committed the instant offense, and the State does not

contend otherwise. The offense was committed on or about July

28, 2001. Appellant's statement indicates that his birthdate is

April 1, 1984. The booking sheet, the arrest report, the arrest

warrant, and the trial court's docket sheet, all contained in

the record, reflect that appellant's date of birth is April 1,

1984. In addition, defense counsel referred to appellant

repeatedly in closing argument as a "17-year-old," and the State

did not object.

In view of

the State's implied concessions and the documents consistently

reflecting appellant's birthdate, the record adequately reflects

that appellant was younger than eighteen years of age at the

time of the offense. Pursuant to the Supreme Court's mandate in

Simmons, appellant's death sentence is hereby reformed

to a sentence of life imprisonment. Tex. R. App. P. 78.1;

Herrin v. State, 125 S.W.3d 436, 444 (Tex. Crim. App.

2002); Collier v. State, 999 S.W.2d 779, 782 (Tex. Crim.

App. 1999). Point of error six is sustained.

We modify the judgment of the trial court to reflect a sentence

of life imprisonment.

(8) In all

other respects, the judgment of the trial court is affirmed.

(9)

Delivered

May 18, 2005

Publish

1.

Unless otherwise indicated, all references to Articles refer to

the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure.

2. This can be inferred

because appellant's fingerprint was found on the bottom of the

car seat, and two of Lorenzo's prints were found elsewhere on

the car seat. Sevilla's prints were not found on the car seat.

3. In a three-count

indictment, appellant was charged with capital murder in the

course of a robbery, committing multiple murders in the same

criminal transaction, and murder of a child under the age of six.

4. Defense counsel

ultimately withdrew his motion to sever after the trial court

made clear that it would not exclude evidence concerning the

other counts, even if they were severed. Appellant does not

complain that his counsel was ineffective in withdrawing the

severance motion.

5. Appellant also claims

that his counsel was ineffective for failing to request an anti-parties

instruction in the court's charge at punishment. Because we

sustain appellant's sixth point of error and reform appellant's

death sentence to a life sentence, any other complaints about

alleged errors in the punishment phase of the trial are moot.

6. Tex. R. Evid. 614.

7. Appellant's written

motion also requested that five other restrictions be placed on

the media coverage of the case. At the hearing, the court

granted some of those requests and denied some of them.

Appellant does not now appear to complain of any of those

rulings.

8. We note that there are

three separate judgments and death sentences in this case, one

for each count. Each judgment and sentence is hereby modified to

reflect a sentence of life imprisonment.

9. In points of error

three and four, appellant complains about alleged errors in the

punishment phase. Because we reform appellant's death sentence

to a sentence of life imprisonment, points three and four are

moot. |