|

No.

90-5551

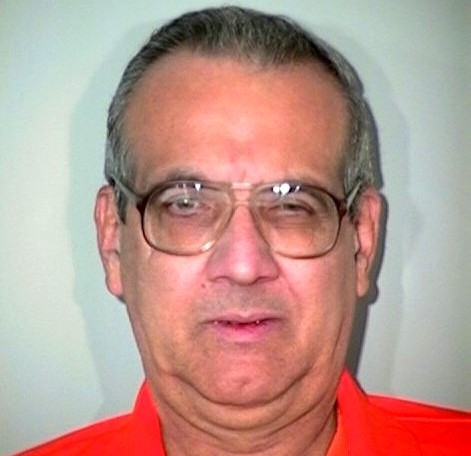

HAROLD SCHAD, Jr.,

PETITIONER v. ARIZONA

[June 21, 1991]

Justice Scalia, concurring in part and

concurring in the judgment.

The crime for which a

jury in Yavapai County, Arizona, convicted Edward Harold Schad in 1985

has existed in the Anglo-American legal system, largely unchanged, since

at least the early 16th century, see 3 J. Stephen, A History of the

Criminal Law of England 45 (1883); R. Moreland, Law of Homicide 9-10

(1952). The common-law crime of murder was the unlawful killing of a

human being by a person with "malice aforethought" or "malice prepense,"

which consisted of an intention to kill or grievously injure, knowledge

that an act or omission would probably cause death or grievous injury,

an intention to commit a felony, or an intention to resist lawful arrest.

Stephen, supra, at 22; see also 4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries

198-201 (1769); 1 M. Hale, Pleas of the Crown 451-466 (1st Am. ed.

1847).

The common law recognized no degrees

of murder; all unlawful killing with malice aforethought received the

same punishment — death. See F. Wharton, Law of Homicide 147 (3d ed.

1907); Moreland, supra, at 199. The rigor of this rule led to

widespread dissatisfaction in this country. See McGautha v.

California, 402 U.S. 183, 198 (1971). In 1794, Pennsylvania divided

common-law murder into two offenses, defining the crimes thus:

"[A]ll murder which shall be

perpetrated by means of poison, or lying in wait, or by any other kind

of willful, deliberate, or premeditated killing; or which shall be

committed in the perpetration, or attempt to perpetrate any arson, rape,

robbery, or burglary, shall be deemed murder of the first degree; and

all other kinds of murder shall be deemed murder in the second degree."

1794 Pa. Laws, ch. 1766, 2.

That statute was widely copied, and

down to the present time the United States and most States have a single

crime of first-degree murder that can be committed by killing in the

course of a robbery as well as premeditated killing. See, e. g.,

18 U.S.C. 1111; Cal. Penal Code Ann. 189 (West 1988 and Supp. 1991); Kan.

Stat. Ann. 21.3401 (Supp. 1990); Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. 750.316 (1991);

Neb. Rev. Stat. 28-303 (1989).

[n.1]

It is Arizona's variant of the 1794 Pennsylvania statute under which

Schad was convicted in 1985 and which he challenges today.

Schad and the dissenting Justices

would in effect have us abolish the crime of first-degree murder and

declare that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires

the subdivision of that crime into (at least) premeditated murder and

felony murder. The plurality rejects that course — correctly, but not in

my view for the correct reason.

As the plurality observes, it has

long been the general rule that when a single crime can be committed in

various ways, jurors need not agree upon the mode of commission. See,

e. g., People v. Sullivan, 173 N. Y. 122, 65 N. E. 989

(1903); cf. H. Joyce, Indictments 561-562, pp. 654-657 (2d ed. 1924); W.

Clark, Criminal Procedure 99-103, pp. 322-330 (2d. ed. 1918); 1 J.

Bishop, Criminal Procedure 434-438, pp. 261-265 (2d. ed. 1872). That

rule is not only constitutional, it is probably indispensable in a

system that requires a unanimous jury verdict to convict. When a woman's

charred body has been found in a burned house, and there is ample

evidence that the defendant set out to kill her, it would be absurd to

set him free because six jurors believe he strangled her to death (and

caused the fire accidentally in his hasty escape), while six others

believe he left her unconscious and set the fire to kill her. While that

seems perfectly obvious, it is also true, as the plurality points out,

see ante, at 7, that one can conceive of novel "umbrella" crimes

(a felony consisting of either robbery or failure to file a tax return)

where permitting a 6-6 verdict would seem contrary to due process.

The issue before us is whether the

present crime falls into the former or the latter category. The

plurality makes heavy weather of this issue, because it starts from the

proposition that "neither the antiquity of a practice nor the fact of

steadfast legislative and judicial adherence to it through the centuries

insulates it from constitutional attack," ante, at 15 (internal

quotations omitted). That is true enough with respect to some

constitutional attacks, but not, in my view, with respect to attacks

under either the procedural component, see Pacific Mutual Life

Insurance Co. v. Haslip, 499 U. S. —, — (1991) (slip op., at

15) (Scalia, J., concurring in judgment), or the so-called

"substantive" component, see Michael H. v. Gerald D., 491

U.S. 110, 121-130 (1989) (plurality opinion), of the Due Process Clause.

It is precisely the historical practices that define what is "due."

"Fundamental fairness" analysis may appropriately be applied to

departures from traditional American conceptions of due process; but

when judges test their individual notions of "fairness" against an

American tradition that is deep and broad and continuing, it is not the

tradition that is on trial, but the judges.

And that is the case here.

Submitting killing in the course of a robbery and premeditated killing

to the jury under a single charge is not some novel composite that can

be subjected to the indignity of "fundamental fairness" review. It was

the norm when this country was founded, was the norm when the Fourteenth

Amendment was adopted in 1868, and remains the norm today. Unless we are

here to invent a Constitution rather than enforce one, it is impossible

that a practice as old as the common law and still in existence in the

vast majority of States does not provide that process which is "due."

If I did not believe that, I might

well be with the dissenters in this case. Certainly the plurality

provides no satisfactory explanation of why (apart from the endorsement

of history) it is permissible to combine in one count killing in the

course of robbery and killing by premeditation. The only point it makes

is that the depravity of mind required for the two may be considered

morally equivalent. Ante, at 17-19. But the petitioner here does

not complain about lack of moral equivalence: he complains that, as far

as we know, only six jurors believed he was participating in a

robbery, and only six believed he intended to kill. Perhaps moral

equivalence is a necessary condition for allowing such a verdict

to stand, but surely the plurality does not pretend that it is

sufficient. (We would not permit, for example, an indictment

charging that the defendant assaulted either X on Tuesday or Y on

Wednesday, despite the "moral equivalence" of those two acts.) Thus, the

plurality approves the Arizona practice in the present case because it

meets one of the conditions for constitutional validity. It does

not say what the other conditions are, or why the Arizona

practice meets them. With respect, I do not think this delivers the "critical

examination," ante, at 17, which the plurality promises as a

substitute for reliance upon historical practice. In fact, I think its

analysis ultimately relies upon nothing but historical practice (whence

does it derive even the "moral equivalence" requirement?) — but to

acknowledge that reality would be to acknowledge a rational limitation

upon our power, which bob-tailed "critical examination" obviously is not.

"Th[e] requirement of [due process] is met if the trial is had according

to the settled course of judicial proceedings. Due process of law is

process due according to the law of the land." Walker v.

Sauvinet, 92 U.S. 90, 93 (1876) (citation omitted).

With respect to the second claim

asserted by petitioner, I agree with Justice Souter's analysis,

and join Part III of his opinion. For these reasons, I would affirm the

judgment of the Supreme Court of Arizona.

*****

Notes

|