|

No.

90-5551

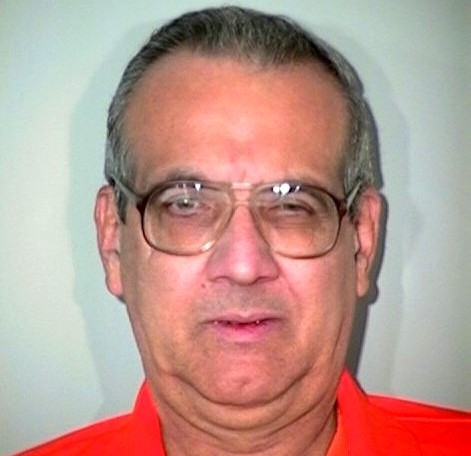

HAROLD SCHAD, Jr.,

PETITIONER v. ARIZONA

[June 21, 1991]

Justice

White, with whom Justice Marshall, Justice Blackmun,

and Justice Stevens join, dissenting.

Because I disagree with the result

reached on each of the two separate issues before the Court, and because

what I deem to be the proper result on either issue alone warrants

reversal of petitioner's conviction, I respectfully dissent.

I

As In re Winship, 397 U.S.

358 (1970), makes clear, due process mandates "proof beyond a reasonable

doubt of every fact necessary to constitute the crime with which [the

defendant] is charged." Id., at 364. In finding that the general

jury verdict returned against petitioner meets the requirements of due

process, the plurality ignores the import of Winship's holding.

In addition, the plurality mischaracter izes the nature of the

constitutional problem in this case.

It is true that we generally give

great deference to the States in defining the elements of crimes. I fail

to see, however, how that truism advances the plurality's case. There is

no failure to defer in recognizing the obvious: that pre-meditated

murder and felony murder are alternative courses of conduct by which the

crime of first-degree murder may be established. The statute provides:

"A murder which is perpetrated by

means of poison or lying in wait, torture or by any other kind of wilful,

deliberate or premeditated killing, or which is committed in avoiding or

preventing lawful arrest or effecting an escape from legal custody, or

in the perpetration of, or attempt to perpetrate, arson, rape in the

first degree, robbery, burglary, kidnapping, or mayhem, or sexual

molestation of a child under the age of thirteen years, is murder of the

first degree. All other kinds of murder are of the second degree." Ariz.

Rev. Stat. Ann. 13-452 (Supp. 1973).

The statute thus sets forth three

general categories of conduct which constitute first-degree murder: a "wilful,

deliberate or premeditated killing"; a killing committed to avoid arrest

or effect escape; and a killing which occurs during the attempt or

commission of various specified felonies. Here, the prosecution set out

to convict petitioner of firstdegree murder by either of two different

paths, premeditated murder and felony murder/robbery. Yet while these

two paths both lead to a conviction for first-degree murder, they do so

by divergent routes possessing no elements in common except the fact of

a murder. In his closing argument to the jury, the prosecutor himself

emphasized the difference between premeditated murder and felony murder:

"There are two types of first degree

murder, two ways for first degree murder to be committed. [One] is

premeditated murder. There are three elements to that. One, that a

killing take place, that the defendant caused someone's death. Secondly,

that he do so with malice. And malice simply means that he intended to

kill or that he was very reckless in disregarding the life of the person

he killed. . . .

"And along with the killing and the

malice, attached to that killing is a third element, that of

premeditation, which simply means that the defendant contemplated that

he would cause death, he reflected upon that.

"The other type of first degree

murder, members of the jury, is what we call felony murder. It only has

two components [sic] parts. One, that a death be caused, and, two, that

that death be caused in the course of a felony, in this case a robbery.

And so if you find that the defendant committed a robbery and killed in

the process of that robbery, that also is first degree murder." App.

6-7.

Unlike premeditated murder, felony

murder does not require that the defendant commit the killing or even

intend to kill, so long as the defendant is involved in the underlying

felony. On the other hand, felony murder — but not premeditated murder —

requires proof that the defendant had the requisite intent to commit and

did commit the underlying felony. State v. McLoughlin, 139

Ariz. 481, 485, 679 P. 2d 504, 508 (1984). Premeditated murder, however,

demands an intent to kill as well as premeditation, neither of which is

required to prove felony murder. Thus, contrary to the plurality's

assertion, see ante, at 13, the difference between the two paths

is not merely one of a substitution of one mens rea for another.

Rather, each contains separate elements of conduct and state of mind

which cannot be mixed and matched at will.

[n.1]

It is particularly fanciful to equate an intent to do no more than rob

with a premeditated intent to murder.

Consequently, a verdict that simply

pronounces a defendant "guilty of first-degree murder" provides no clues

as to whether the jury agrees that the three elements of premed itated

murder or the two elements of felony murder have been proven beyond a

reasonable doubt. Instead, it is entirely possible that half of the jury

believed the defendant was guilty of premeditated murder and not guilty

of felony murder/robbery, while half believed exactly the reverse. To

put the matter another way, the plurality affirms this con viction

without knowing that even a single element of either of the ways for

proving first-degree murder, except the fact of a killing, has been

found by a majority of the jury, let alone found unanimously by the jury

as required by Arizona law. A defendant charged with first-degree murder

is at least entitled to a verdict — something petitioner did not get in

this case as long as the possibility exists that no more than six jurors

voted for any one element of first-degree murder, except the fact of a

killing. [n.2]

The means by which the plurality

attempts to justify the result it reaches do not withstand scrutiny. In

focusing on our vagueness cases, see ante, at 6-7, the plurality

misses the point. The issue is not whether the statute here is so vague

that an individual cannot reasonably know what conduct is criminalized.

Indeed, the statute's specificity renders our vagueness cases

inapplicable. The problem is that the Arizona statute, under a single

heading, criminalizes several alternative patterns of conduct. While a

State is free to construct a statute in this way, it violates due

process for a State to invoke more than one statutory alternative, each

with different specified elements, without requiring that the jury

indicate on which of the alternatives it has based the defendant's guilt.

The plurality concedes that "nothing

in our history suggests that the Due Process Clause would permit a State

to convict anyone under a charge of `Crime' so generic that any

combination of jury findings of embezzlement, reckless driving, murder,

burglary, tax evasion, or littering, for example, would suffice for

conviction." Ante, at 7. But this is very close to the effect of

the jury verdict in this case. Allowing the jury to return a generic

verdict following a prosecution on two separate theories with specified

elements has the same effect as a jury verdict of "guilty of crime"

based on alternative theories of embezzlement or reckless driving. Thus

the statement that "[i]n Arizona, first degree murder is only one crime

regardless whether it occurs as a premeditated murder or a felony murder,"

State v. Encinas, 132 Ariz. 493, 496, 647 P. 2d 624, 627

(1982), neither recognizes nor resolves the issue in this case.

The plurality likewise misses the

mark in attempting to compare this case to those in which the issue

concerned proof of facts regarding the particular means by which a crime

was committed. See ante, at 5-6. In the case of burglary, for

example, the manner of entering is not an element of the crime; thus,

Winship would not require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of such

factual details as whether a defendant pried open a window with a

screwdriver or a crowbar. It would, however, require the jury to find

beyond a rea sonable doubt that the defendant in fact broke and entered,

because those are the "fact[s] necessary to constitute the crime." 397

U. S., at 364. [n.3]

Nor do our cases concerning the

shifting of burdens and the creation of presumptions help the

plurality's cause. See ante, at 12. Although this Court

consistently has given deference to the State's definition of a crime,

the Court also has made clear that having set forth the elements of a

crime, a State is not free to remove the burden of proving one of those

elements from the prosecution. For example, in Sand strom

v. Montana, 442 U.S. 510 (1979), the Court recognized that "under

Montana law, whether the crime was committed purposely or knowingly is a

fact necessary to consti tute the crime of deliberate homicide," and

stressed that the State therefore could not shift the burden of proving

lack of intent to the defendant. Id., at 520-521. Conversely, in

Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197, 205-206 (1977), the

Court found that it did not violate due process to require a defendant

to establish the affirmative defense of extreme emotional disturbance,

because "[t]he death, the intent to kill, and causation are the facts

that the State is required to prove beyond a reasonable doubt if a

person is to be convicted of murder. No further facts are either

presumed or inferred in order to constitute the crime." Here, the

question is not whether the State "must be permitted a degree of

flexibility" in defining the elements of the offense. See ante,

at 12. Surely it is entitled to that deference. But having determined

that premeditated murder and felony murder are separate paths to

establishing first-degree murder, each containing a separate set of

elements from the other, the State must be held to its choice.

[n.4]

Cf. Evitts v. Lucey, 469 U.S. 387, 401 (1985). To allow

the State to avoid the consequences of its legislative choices through

judicial interpretation would permit the State to escape federal

constitutional scrutiny even when its actions violate rudimentary due

process.

The suggestion that the state of

mind required for felony murder/robbery and that for premeditated murder

may reasonably be considered equivalent, see ante, at 18, is not

only unbelievable, but it also ignores the distinct consequences that

may flow from a conviction for each offense at sentencing. Assuming that

the requisite statutory aggravating circumstance exists, the death

penalty may be imposed for premeditated murder, because a conviction

necessarily carries with it a finding that the defendant intended to

kill. See Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. 13-703 (1989). This is not the case with

felony murder, for a conviction only requires that the death occur

during the felony; the defendant need not be proven to be the killer.

Thus, this Court has required that in order for the death penalty to be

imposed for felony murder, there must be a finding that the defendant in

fact killed, attempted to kill, or intended that a killing take place or

that lethal force be used, Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S.

782, 797 (1982), or that the defendant was a major participant in the

felony and exhibited reckless indifference to human life, Tison

v. Arizona, 481 U.S. 137, 158 (1987).

In the instant case, the general

verdict rendered by the jury contained no finding of intent or of actual

killing by petitioner. The sentencing judge declared, however:

"[T]he court does consider the fact

that a felony murder instruction was given in mitigation, however there

is not evidence to indicate that this murder was merely incidental to a

robbery. The nature of the killing itself belies that. . . .

"The court finds beyond a reasonable

doubt that the defendant attempted to kill Larry Grove, intended to kill

Larry Grove and that defendant did kill Larry Grove.

"The victim was strangled to death

by a ligature drawn very tightly about the neck and tied in a double

knot. No other reasonable conclusion can be drawn from the proof in this

case, notwithstanding the felony murder instruction." Tr. 8-9 (Aug. 29,

1985).

Regardless of what the jury actually

had found in the guilt phase of the trial, the sentencing judge believed

the murder was premeditated. Contrary to the plurality's suggestion, see

ante, at 18, n. 9, the problem is not that a general verdict

fails to provide the sentencing judge with sufficient information

concerning whether to impose the death sentence. The issue is much more

serious than that. If in fact the jury found that premeditation was

lacking, but that petitioner had committed felony murder/robbery, then

the sentencing judge's finding was in direct contravention of the jury

verdict. It is clear, therefore, that the general jury verdict creates

an intolerable risk that a sentencing judge may subsequently impose a

death sentence based on findings that contradict those made by the jury

during the guilt phase, but not revealed by their general verdict. Cf.

State v. Smith, 160 Ariz. 507, 513, 774 P. 2d 811, 817

(1989).

II

I also cannot agree that the

requirements of Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980), were

satisfied by the instructions and verdict forms in this case. Beck

held that "when the evidence unquestionably establishes that the

defendant is guilty of a serious, violent offense — but leaves some

doubt with respect to an element that would justify conviction of a

capital offense — the failure to give the jury the `third option' of

convicting on a lesser included offense would seem inevitably to enhance

the risk of an unwarranted conviction." Id., at 637. The majority

finds Beck satisfied because the jury here had the opportunity to

convict petitioner of second-degree murder. See ante, at 20-21.

But that alternative provided no "third option" to a choice between

convicting petitioner of felony murder/robbery and acquitting him

completely, because, as the State concedes, see Tr. of Oral Arg. 51-52,

second-degree murder is a lesser included offense only of premeditated

murder. Thus, the Arizona Supreme Court has declared that " `[t]he jury

may not be instructed on a lesser degree of murder than first

degree where, under the evidence, it was committed in the course of a

robbery.' " State v. Clayton, 109 Ariz. 587, 595, 514 P.

2d 720, 728 (1973), quoting State v. Kruchten, 101 Ariz.

186, 196, 417 P. 2d 510, 520 (1966), cert. denied, 385 U.S. 1043 (1967)

(emphasis added). Consequently, if the jury believed that the course of

events led down the path of felony murder/robbery, rather than

premeditated murder, it could not have convicted petitioner of second-degree

murder as a legitimate "third option" to capital murder or acquittal.

The State asserts that felony murder

has no lesser included offenses.

[n.5]

In order for a defendant to be convicted of felony murder, however,

there must be evidence to support a conviction on the underlying felony,

and the jury must be instructed as to the elements of the underlying

felony. Although the jury need not find that the underlying felony was

completed, the felony murder statute requires there to be at least an

attempt to commit the crime. As a result, the jury could not have

convicted petitioner of felony murder/robbery without first finding him

guilty of robbery or attempted robbery.

[n.6]

Indeed, petitioner's first conviction was reversed because the

trial judge had failed to instruct the jury on the elements of robbery.

142 Ariz. 619, 691 P. 2d 710 (1984). As the Arizona Supreme Court

declared, "Fundamental error is present when a trial judge fails to

instruct on matters vital to a proper consideration of the evidence.

Knowledge of the elements of the underlying felonies was vital for the

jurors to properly consider a felony murder theory." Id., at

620-621, 691 P. 2d, at 711-712 (citation omitted).

It is true that the rule in Beck

only applies if there is in fact a lesser included offense to that with

which the defendant is charged, for "[w]here no lesser included offense

exists, a lesser included offense instruction detracts from, rather than

enhances, the rationality of the process." Spaziano v.

Florida, 468 U.S. 447, 455 (1984). But while deference is due state

legislatures and courts in defining crimes, this deference has

constitutional limits. In the case of a compound crime such as felony

murder, in which one crime must be proven in order to prove the other,

the underlying crime must, as a matter of law, be a lesser included

offense of the greater.

Thus, in the instant case, robbery

was a lesser included offense of the felony murder/robbery for which

petitioner was tried. The Arizona Supreme Court acknowledged that "the

evidence supported an instruction and conviction for robbery," had

robbery been a lesser included offense of felony murder/robbery. 163

Ariz. 411, 417, 788 P. 2d 1162, 1168 (1989). Consequently, the evidence

here met "the independent prerequisite for a lesser included offense

instruction that the evidence at trial must be such that a jury could

rationally find the defendant guilty of the lesser offense, yet acquit

him of the greater." Schmuck v. United States, 489 U.S.

705, 716, n. 8 (1989); see Keeble v. United States, 412

U.S. 205, 208 (1973). Due process required that the jury be given the

opportunity to convict petitioner of robbery, a necessarily lesser

included offense of felony murder/robbery. See Stevenson v.

United States, 162 U.S. 313, 319-320 (1896).

Nor is it sufficient that a "third

option" was given here for one of the prosecution's theories but not the

other. When the State chooses to proceed on various theories, each of

which has lesser included offenses, the relevant lesser included

instructions and verdict forms on each theory must be given in

order to satisfy Beck. Anything less renders Beck, and the

due process it guarantees, meaningless.

With all due respect, I dissent.

*****

Notes

|