|

Syllabus

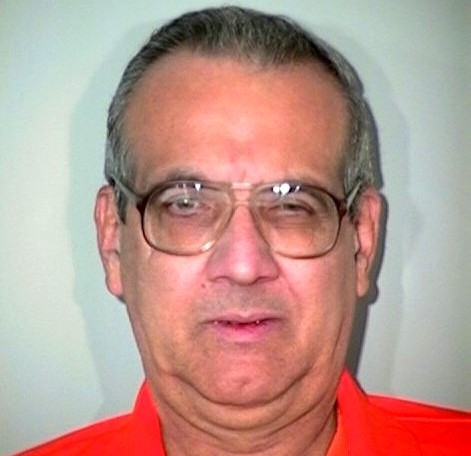

SCHAD

v.

ARIZONA

certiorari to the supreme court of arizona

No.

90-5551.

Argued

February 27, 1991

— Decided June 21, 1991

After he was found

with a murder victim's vehicle and other belongings, petitioner Schad

was indicted for first-degree murder. At trial, the prosecutor advanced

both premeditated and felony murder theories, against which Schad

claimed that the circumstantial evidence proved at most that he was a

thief, not a murderer. The court refused Schad's request for an

instruction on theft as a lesser included offense, but charged the jury

on second-degree murder. The jury convicted him of first-degree murder,

and he was sentenced to death. The State Supreme Court affirmed,

rejecting Schad's contention that the trial court erred in not requiring

the jury to agree on a single theory of firstdegree murder. The court

also rejected Schad's argument that Beck v. Alabama, 447

U.S. 625, required an instruction on the lesser included offense of

robbery.

Held: The judgment is

affirmed.

163 Ariz. 411, 788 P. 2d 1162,

affirmed.

Justice Souter delivered the

opinion of the Court with respect to Part III, concluding that Beck

v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 — which held unconstitutional a state

statute prohibiting lesser included offense instructions in capital

cases — did not entitle Schad to a jury instruction on robbery. Beck

was based on the concern that a jury convinced that the defendant

had committed some violent crime but not convinced that he was guilty of

a capital offense might nonetheless vote for a capital conviction if the

only alternative was to set him free with no punishment at all. See

id., at 629, 630, 632, 634, 637, 642-643, and n. 19. This concern

simply is not implicated here, since the jury was given the "third

option" of finding Schad guilty of a lesser included noncapital offense,

second-degree murder. It would be irrational to assume that the

jury chose capital murder rather than second-degree murder as its means

of keeping a robber off the streets, and, thus, the trial court's choice

of instructions sufficed to ensure the verdict's reliability. Pp. 19-22.

Justice Souter, joined by

The Chief Justice, Justice O'Connor, and Justice Kennedy,

concluded in Part II that Arizona's characterization of first-degree

murder as a single crime as to which a jury need not agree on one of the

alternative statutory theories of premeditated or felony murder is not

unconstitutional. Pp. 4-19.

(a) The relevant enquiry is not, as

Schad argues, whether the Constitution requires a unanimous jury in

state capital cases. Rather, the real question here is whether it was

constitutionally acceptable to permit the jury to reach one verdict

based on any combination of the alternative findings. Pp. 4-5.

(b) The long-established rule that a

jury need not agree on which overt act, among several, was the means by

which a crime was committed, provides a useful analogy.

Nevertheless, the Due Process Clause does place limits on a State's

capacity to define different states of mind as merely alternative means

of committing a single offense; there is a point at which differences

between those means become so important that they may not reasonably be

viewed as alternatives to a common end, but must be treated as

differentiating between what the Constitution requires to be treated as

separate offenses subject to separate jury findings. Pp. 5-11.

(c) It is impossible to lay down any

single test for determining when two means are so disparate as to

exemplify two inherently separate offenses. Instead, the concept of due

process, with its demands for fundamental fairness and for the

rationality that is an essential component of that fairness, must serve

as the measurement of the level of definitional and verdict specificity

permitted by the Constitution. P. 11.

(d) The relevant enquiry must be

undertaken with a threshold presumption of legislative competence.

Decisions about what facts are material and what are immaterial, or, in

terms of In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, 364, what "fact[s] [are]

necessary to constitute the crime," and therefore must be proved

individually, and what facts are mere means, represent value choices

more appropriately made in the first instance by a legislature than by a

court. There is support for such restraint in this Court's "burden-shifting"

cases, which have made clear, in a slightly different context, that the

States must be permitted a degree of flexibility in determining what

facts are necessary to constitute a particular offense within the

meaning of Winship. See, e. g., Patterson v. New York,

432 U.S. 197, 201-202, 210. Pp. 11-13.

(e) In translating the due process

demands for fairness and rationality into concrete judgments about the

adequacy of legislative determinations, courts should look both to

history and widely shared state practice as guides to fundamental values.

See, e. g., id., at 202. Thus it is significant here that

Arizona's equation of the mental states of premeditated and felony

murder as a species of the blameworthy state of mind required to prove a

single offense of first-degree murder finds substantial historical and

contemporary echoes. See, e. g., People v. Sullivan, 173

N. Y. 122, 127, 65 N. E. 989, 989-990; State v. Buckman,

237 Neb. 936, — N. W. 2d —. Pp. 13-17.

(f) Whether or not everyone would

agree that the mental state that precipitates death in the course of

robbery is the moral equivalent of premeditation, it is clear that such

equivalence could reasonably be found. See Tison v. Arizona,

481 U.S. 137, 157-158. This is enough to rule out the argument that a

moral disparity bars treating the two mental states as alternative means

to satisfy the mental element of a single offense. Pp. 17-18.

(g) Although the foregoing

considerations may not exhaust the universe of those potentially

relevant, they are sufficiently persuasive that the jury's options in

this case did not fall beyond the constitutional bounds of fundamental

fairness and rationality. P. 19.

Justice Scalia would reach

the same result as the plurality with respect to Schad's verdict-specificity

claim, but for a different reason. It has long been the general rule

that when a single crime can be committed in various ways, jurors need

not agree upon the mode of commission. As the plurality observes, one

can conceive of novel "umbrella" crimes that could not, consistent with

due process, be submitted to a jury on disparate theories. But first-degree

murder, which has in its basic form existed in our legal system for

centuries, does not fall into that category. Such a traditional crime,

and a traditional mode of submitting it to the jury, do not need to pass

this Court's "fundamental fairness" analysis; and the plurality provides

no persuasive justification other than history in any event. Pp. 1-5.

Souter, J., announced the

judgment of the Court and delivered the opinion of the Court with

respect to Part III, in which Rehnquist, C. J., and O'Connor,

Scalia, and Kennedy, JJ., joined, and an opinion with respect

to Parts I and II, in which Rehnquist, C. J., and O'Connor

and Kennedy, JJ., joined. Scalia, J., filed an opinion

concurring in part and concurring in the judgment. White, J.,

filed a dissenting opinion, in which Marshall, Blackmun, and

Stevens, JJ., joined. |