Short v. State, 980 P.2d 1081 (Okla.Crim.

1999) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted, in the District Court,

Oklahoma County, Charles L. Owens, J., of first degree murder and

five counts of attempting to kill after former conviction of two or

more felonies, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The

Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, V.P.J., held that: (1) as a

matter of apparent first impression, doctrine of transferred intent

applied to crime of attempt to kill another; (2) state's peremptory

challenges against two jurors were race neutral; (3) exclusion of

cellmate's testimony was appropriate sanction for discovery

violation; (4) probative value was not substantially outweighed by

unfair prejudice as to admission of photographs of drawings on

defendant's jail cell wall depicting attempted-murder victim; (5)

there was no plain error as to corroboration of defendant's

confession to firebombing apartment; (6) victim impact evidence did

not violate defendant's constitutional rights; (7) trial counsel was

not ineffective; and (8) evidence supported aggravating

circumstances at sentencing. Judgment and sentences affirmed;

application for hearing on Sixth Amendment claims denied. Johnson,

J., specially concurred and filed an opinion. Chapel, J., concurred

in results.

LUMPKIN, Vice Presiding Judge:

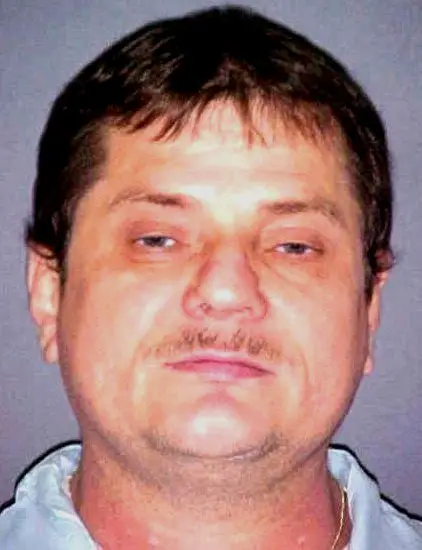

¶ 1 Appellant Terry Lyn Short was tried by jury

and convicted of First Degree Murder (Count I) (21 O.S.1991, §

701.7) and five counts of Attempting to Kill, After Former

Conviction of Two or More Felonies (Counts II-VI) (21 O.S.1991, §

652), Case No. CF-95-216, in the District Court of Oklahoma County.

In Count I, the jury found the existence of three (3) aggravating

circumstances and recommended the punishment of death. In Counts II-IV,

the jury recommended as punishment one hundred (100) years

imprisonment. In Counts V and VI, the jury recommended two (200)

hundred years imprisonment. The trial court sentenced accordingly.

From this judgment and sentence Appellant has perfected this

appeal.FN1

FN1. Appellant's Petition in Error was filed in

this Court on October 17, 1997. Appellant's brief was filed April

29, 1998. The State's brief was filed July 28, 1998. Appellant's

reply brief was filed August 17, 1998 The case was submitted to the

Court August 21, 1998. Oral argument was held January 26, 1999.

¶ 2 Appellant was convicted of the murder of Ken

Yamamoto. Mr. Yamamoto lived in apartment number 227 at the Royal

Chateau Apartments in Oklahoma City. Directly beneath that apartment,

in apartment number 127 lived Tammy Gardner, her two minor children,

and Brenda Gardner, Tammy's sister.

¶ 3 Brenda Gardner and Appellant had been dating

for some time. Appellant was abusive to Brenda and on several

occasions threatened to kill Brenda and her family. At approximately

3:00 a.m. on January 8, 1995, Tammy and Brenda were awakened by a

banging on the front door. When Brenda called out, the noise at the

door stopped. Approximately thirty (30) minutes later, Robert Hines,

the father of one of Tammy's children, knocked on the front door. He

was unable to enter through the door as it was jammed. Hines entered

the apartment through the patio door. He repaired the front door and

remained to visit with Tammy and Brenda. At approximately 5:00 a.m.,

Brenda looked out the patio door to see Appellant standing beside

Hines' truck. Upon hearing Brenda's announcement of Appellant's

presence, Hines moved towards the patio door to look out. Appellant

then threw a homemade explosive through the patio door, burning

Hines and the apartment. Despite the burning of his left arm, Hines

was able to run out of the apartment. Tammy, Brenda and the children

escaped unharmed.

¶ 4 The fire spread quickly and caused Mr.

Yamamoto's apartment to collapse into the inferno beneath it. Mr.

Yamamoto was asleep at the time of the fire, and awoke to find

himself burned and surrounded by paramedics. Mr. Yamamoto was

severely burned, suffering thermal burns to 95 percent of his body.

Mr. Yamamoto was transported to the hospital where he died several

hours later as a result of the burns.

¶ 5 That same evening, Appellant phoned his

cousin, David Davis, and asked him to pick him up and accompany him

to the police station so he could surrender. At Appellant's request,

Davis took Appellant a complete change of clothing. After changing

his clothes, and accompanied by Davis, Appellant surrendered to the

authorities.

¶ 6 Appellant raises fifteen propositions of

error in his appeal. These propositions will be addressed in the

order in which they arose at trial.

PRE-TRIAL ISSUES

¶ 7 Appellant challenges the trial court's

determination of his competency to stand trial in his fourth

assignment of error. At the time of Appellant's trial, the standard

of proof to be used in competency determinations required a

defendant to prove his/her incompetency by “clear and convincing”

evidence. That standard has since been held unconstitutional, and

“preponderance of the evidence” has been held the proper standard of

proof. Cooper v. Oklahoma, 517 U.S. 348, 116 S.Ct. 1373, 134 L.Ed.2d

498 (1996). Appellant argues that since he was found competent under

an unconstitutional standard of proof, his case should be reversed

and remanded in order that his competence can be evaluated under the

proper “preponderance of the evidence” standard.

¶ 8 Pursuant to an order of the trial court, Dr.

Edith King examined Appellant in the Oklahoma County Jail. Dr. King

reported: 1) Appellant was able to appreciate the nature of the

charges against him; 2) he was able to consult with his lawyer and

rationally assist in the preparation of his defense; 3) he was not

mentally ill; and 4) if Appellant were released without treatment,

therapy or training he would pose a significant threat to the life

or safety of himself and others.FN2 At the post-examination

competency hearing, defense counsel stipulated to Dr. King's

findings that Appellant understood the charges against him and could

assist in his defense and that if she were called to testify her

testimony would be consistent with her report. No other evidence was

offered or presented. Based upon the evidence before it, the trial

court found Appellant competent to stand trial.

FN2. This finding is not inconsistent with the

other findings. It is based on Appellant's anti-social personality

characteristics which could cause him to become dangerous to others

and not on his competency. (O.R.175).

¶ 9 Whether a defendant is competent to stand

trial is a matter left to the sound discretion of the trial court.

Siah v. State, 837 P.2d 485, 487 (Okl.Cr.1992). This Court can

review that decision, applying the proper standard of proof, i.e.

“preponderance of the evidence.” See Smith v. State, 932 P.2d 521,

528 (Okl.Cr.1996), cert. denied, 521 U.S. 1124, 117 S.Ct. 2522, 138

L.Ed.2d 1023 (1997). The standard of review on appeal is whether

there is any competent evidence reasonably supporting the trier of

fact. Gilbert v. State 951 P.2d 98, 105 (Okl.Cr.1997). When the

issue of competency is tried before a judge, his finding will not be

disturbed on appeal if it is supported by sufficient evidence. Id.

¶ 10 Here, the uncontradicted evidence showed

that Appellant knew the nature of the proceedings and possessed a

rational understanding of them. The defense failed to prove, even by

a preponderance of the evidence, that Appellant was incompetent to

stand trial. Because the evidence in this case so strongly supports

the finding that Appellant was competent, we find the trial court

did not abuse its discretion in finding Appellant competent to stand

trial, and this case need not be remanded for a new determination on

the issue. Accordingly, this assignment of error is denied.

JURY SELECTION

¶ 11 In his eleventh assignment of error,

Appellant contends the State's race-neutral reasons for excusing

venirepersons Smith and Frazier were pretextual and their excusal

from the jury violated the Equal Protection Clause under Batson v.

Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 98, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 1724, 90 L.Ed.2d 69

(1986).

¶ 12 Batson establishes a three (3) part analysis:

1) the defendant must make a prima facie showing that the prosecutor

has exercised peremptory challenges on the basis of race; 2) after

the requisite showing has been made, the burden shifts to the

prosecutor to articulate a race neutral explanation related to the

case for striking the juror in question; and 3) the trial court must

determine whether the defendant has carried his burden of proving

purposeful discrimination. Id. As for the second requirement, the

Supreme Court noted the race-neutral explanation by the prosecutor

need not rise to the level justifying excusal for cause, but it must

be a “clear and reasonably specific” explanation of his “legitimate

reasons” for exercising the challenges. Neill v. State, 896 P.2d

537, 546 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1080, 116 S.Ct. 791,

133 L.Ed.2d 740, (1996), quoting Batson, 476 U.S. at 98, n. 20, 106

S.Ct. at 1723, n. 20. The trial court's findings as to

discriminatory intent are entitled to great deference. Id. Our

review is only for clear error by the trial court, Pennington v.

State, 913 P.2d 1356, 1365 (Okl.Cr.1995), cert. denied, 519 U.S.

841, 117 S.Ct. 121, 136 L.Ed.2d 72 (1996) and we review the record

in the light most favorable to the trial court's ruling. Neill, 896

P.2d at 546.

¶ 13 A review of the record in this case shows

the prosecutor offered raceneutral explanations for striking Ms.

Smith and Ms. Frazier from the panel. A neutral explanation in the

context of our analysis here means an explanation based on something

other than the race of the juror. At this step of the inquiry, the

issue is the facial validity of the prosecutor's explanation. Unless

a discriminatory intent is inherent in the prosecutor's explanation,

the reason offered will be deemed race neutral. Id., quoting

Hernandez v. New York, 500 U.S. 352, 360, 111 S.Ct. 1859, 1866, 114

L.Ed.2d 395, 406 (1991). See also Purkett v. Elem, 514 U.S. 765, 115

S.Ct. 1769, 1770-71, 131 L.Ed.2d 834 (1995); Turrentine v. State,

965 P.2d 955, 964 (Okl.Cr.1998).

¶ 14 Here, the prosecutor used his second

peremptory challenge to excuse venireperson Smith. He explained that

she had a brother with two convictions and that because of the way

she answered questions posed to her, the prosecutor was not sure she

was being truthful. After noting that Ms. Smith was a black female,

the trial court, over defense counsel's objection, accepted the

prosecutor's explanation and struck the juror. The prosecutor used

his last peremptory challenge to excuse venireperson Frazier stating

that she had been convicted of an offense and placed on probation.

He added “I don't want to gamble a verdict in this case on someone

who I personally prosecuted.” (Tr. II, pg.218). Again noting that

the venireperson was a black female, the trial court, acknowledging

its own reservations about the explanation and over defense

counsel's objection, agreed to strike Ms. Frazier from the jury. (Tr.

II, pg.218-220).FN3 FN3. The record reflects that with the excusal

of Ms. Smith and Ms. Frazier, no black individuals were left to sit

on the jury. We also note for the record that Appellant is a white

male. However, we recognize the Batson rule applies to race based

exclusions even where the defendant and the potential juror do not

share the same race. Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400, 111 S.Ct. 1364,

113 L.Ed.2d 411 (1991).

¶ 15 The prosecutor's explanations were facially

valid and do not reveal an intent to discriminate against the

potential jurors on account of race. Excusal of a potential juror

because of a prior criminal record or because of the criminal

records of family members are legitimate reasons for removal.

Further, these same reasons were used to excuse non-minority members

of the venire, i.e., a white female was excused because her husband

had a prior criminal record, albeit approximately twenty-six years

had passed since his two year incarceration. The fact that this

reason, criminal records by family members, was not used in every

instance in which it arose to excuse potential jurors, does not

lessen its legitimacy as a race-neutral explanation.

¶ 16 Once the prosecutor offers a race-neutral

basis for the exercise of the peremptory challenge, it is the duty

of the trial court to determine if the defendant has established

purposeful discrimination. [I]n the typical peremptory challenge

inquiry, the decisive question will be whether counsel's race

neutral explanation for a peremptory challenge should be believed.

There will seldom be much evidence bearing on that issue, and the

best evidence often will be the demeanor of the attorney who

exercises the challenge.... [E]valuation of the prosecutor's state

of mind based on demeanor and credibility lies ‘peculiarly within a

trial judge's province.’ Turrentine, 965 P.2d at 965, quoting

Hernandez, 500 U.S. at 365, 111 S.Ct. at 1859, 114 L.Ed.2d at 409.

¶ 17 Here, the trial court chose to believe the

prosecutor's race-neutral explanations for striking the jurors in

question, rejecting Appellant's assertion that the reasons were

pretextual. The trial court's decision on the issue of

discriminatory intent will not be overturned unless we are convinced

that the determination is clearly erroneous. Hernandez, 500 U.S. at

369, 111 S.Ct. at 1871-72, 114 L.Ed.2d at 412. See also Simpson v.

State, 827 P.2d 171, 175 (Okl.Cr.1992). Apart from the prosecutor's

demeanor, which we are not able to adequately review from the

written transcripts, the court could have relied on the facts that

the prosecutor defended his use of the peremptory challenges without

being asked to do so by the judge, that no history of the prosecutor

seeking to purposefully discriminate against jurors on the basis of

race was established, and that the record in this case reveals that

race was simply not an issue. No allegations were made that the

commission of the offense or the prosecution of Appellant were in

any way racially motivated. Therefore, we find no error in the trial

court's determination that the prosecutor did not discriminate on

the basis of race and that Appellant failed to carry his burden of

showing purposeful discrimination. This assignment of error is

denied.

FIRST STAGE ISSUES

¶ 18 In his first assignment of error, Appellant

contends reversible error occurred when the trial court prohibited

the defense from calling Mark Bayless as a witness. Appellant

asserts Bayless was a critical witness to rebut the State's case-in-chief

and that despite the failure of the defense to endorse Mr. Bayless

prior to trial, exclusion of his testimony violated the

constitutional compulsory process clause. Okla. Const. art. II, §

20; U.S. Const. amend. VI.

¶ 19 Prior to trial, Appellant was detained in a

“holding cell” in the Oklahoma City Jail. This “holding cell”

contained several people who were awaiting transportation to the

county jail. In the “holding cell” at the same time as Appellant

were inmates Jay Brown and Mark Bayless. Testifying in the State's

case-in-chief, Brown testified that Appellant said he thought he

knew Brown, a fact which Brown denied, and proceeded to tell Brown

that he was in jail for firebombing an apartment complex. Brown also

testified that he observed Appellant draw sexually explicit pictures

of a woman on the walls of the cell. Next to the pictures, Brown saw

Appellant write the words “die Brenda G”, “Brenda G is a slut”, and

“burn Brenda G”. Brown further testified that sometime later he and

Appellant were talking and Appellant told him that he had dated

Brenda G.; they had both been heroin addicts who stole to support

their addiction; he eventually got a job at “Two Guys Auto” and he

and Brenda moved into an apartment. Appellant also said that

Brenda's sister, Tammy, and her boyfriend Robert Hines, moved in

with them. Appellant stated that one day he came home from lunch and

found Brenda having sexual intercourse with Hines; that he looked

for a gun but could not find one, so he came up with the idea of

putting gasoline in a Coke bottle and a sock in the top. He then

went to the apartment where Brenda was living, threw the coke bottle

inside, saw it hit Hines in the back of the head, shut the door and

ran away.

¶ 20 Brown was the last witness presented in the

State's case-in-chief. The first witness called by the defense was

Mark Bayless. The State objected as Bayless was not endorsed as a

witness. Acknowledging this fact, defense counsel noted that he had

given the prosecutor a handwritten note three (3) days earlier

stating that the defense would call Bayless as a witness. Defense

counsel argued that Bayless would refute Brown's testimony

concerning Appellant's confession and would testify that he observed

someone other than Appellant draw the sexually explicit pictures on

the jail cell wall. The trial court upheld the State's motion to

prohibit the testimony finding the defense had violated the rules of

discovery by failing to list Bayless as a witness. The court also

found that even if called Bayless was not a crucial witness as he

was not present during the conversations between Appellant and Brown

and could not testify as to the content of those conversations.

Defense counsel then offered Bayless as a rebuttal witness to the

fact that Appellant did not draw the obscene pictures. The trial

court denied the request.

¶ 21 Prior to trial, discovery motions were filed

by both the prosecution and the defense. Eleven days prior to trial,

the defense filed its witness list and summary of testimony. Mark

Bayless was not listed as a witness. The failure of the defense to

list Bayless as a witness was a violation of the Discovery Code. 22

O.S.Supp.1996, § 2001 et. seq. The trial courts are empowered to

order the appropriate relief for the failure to comply with a

discovery order. 22 O.S.Supp.1996, § 2002(E)(2). This relief may

include prohibition of a witnesses testimony. Wilkerson v. District

Court of McIntosh County, 839 P.2d 659, 661 (Okl.Cr.1992).

¶ 22 In Wilkerson, this Court recognized that

“few rights are more fundamental than that of an accused to present

witnesses in his own defense.” Id. We also acknowledged the

preclusion of material defense witnesses from testifying is the

severest sanction for discovery violations, citing Taylor v.

Illinois, 484 U.S. 400, 108 S.Ct. 646, 98 L.Ed.2d 798 (1988). Id.

See also Allen v. State, 944 P.2d 934, 937 (Okl.Cr.1997); Wisdom v.

State, 918 P.2d 384, 396 (Okl.Cr.1996). However, preclusion of

testimony is appropriate in certain circumstances. In Wilkerson we

stated: When the discovery violations are flagrant, such as being

designed to conceal a plan to present fabricated testimony or being

willful and motivated by a desire to obtain a tactical advantage,

then the preclusion sanction could be entirely appropriate and

consistent with the purposes of the compulsory process clause.

Petitioners have not established that, by

imposing the sanction, Respondent has exercised power unauthorized

by law or that Petitioners' remedies on appeal are not adequate and

appropriate. Rule 10.6(A), supra. They have not established that

their witnesses, precluded from testifying, are material or that

their case has been substantially prejudiced by the discovery

sanction. (citation omitted) Moreover, from the facts developed at

this point in the case, this Court is unable to determine that the

preclusion sanction is not appropriate. (citation omitted).

Wilkerson, 839 P.2d at 661. Based upon the record before us, we are

unable to determine that the preclusion of Bayless's testimony was

not an appropriate sanction. The preliminary hearing in this case

was held approximately one year and a half prior to trial. Brown

testified at the preliminary hearing and gave essentially the same

testimony as he did at trial. Appellant has failed to explain why he

did not notify the State about Bayless's testimony until the start

of trial.

¶ 23 Further, Bayless was not a material witness.

He was not a party to the conversations between Brown and Appellant.

Therefore, he could not testify as to the truthfulness of Brown's

testimony regarding Appellant's confession. At most, Bayless could

impeach Brown only as to the testimony regarding who drew the

pictures on the jail cell wall. Bayless was not a witness to the

actual crime and therefore could not have refuted the testimony of

the eyewitnesses. Because Bayless was not a material witness, and as

Appellant has failed to establish that he was substantially

prejudiced by the exclusion of the testimony, we find no error in

the trial court's ruling.

¶ 24 Relying on Spencer v. State, 795 P.2d 1075,

1078 (Okl.Cr.1990), Wooldridge v. State, 659 P.2d 943, 947 (Okl.Cr.1983)

and Luna v. State, 815 P.2d 1197, 1199 (Okl.Cr.1991) Appellant

argues that Bayless was a rebuttal witness for which no notice to

the State was required. The cases cited by Appellant are wholly

unavailing to his position. These cases concern the admission of

testimony of witnesses for the State who had not been endorsed. In

these cases, this Court found that since the evidence being rebutted

had not been presented until the defendant's case-in-chief, the

State could not have known that the rebuttal witness would be

required and therefore was excused from the obligation of endorsing

the witness, even though the witness could have been called in its

case-in-chief.

¶ 25 In the present case, the defense knew from

the preliminary hearing that it would need to impeach Brown's

testimony. Bayless's testimony was not offered to explain any

unexpected evidence from the State. It was only after Bayless was

prohibited from testifying in the case-in-chief that he was offered

as a rebuttal witness. Bayless was not a true rebuttal witness. He

was a rebuttal witness only in as much as every defense witness is a

“rebuttal” witness to the State's case. Further, under usual trial

proceedings, rebuttal is an opportunity for the State to present

witnesses, for whom no notice is required, to rebut the defense

case-in-chief. The defense does not present rebuttal witnesses until

surrebuttaI. Bayless's testimony does not qualify as surrebuttal

evidence. Accordingly, we find Bayless was subject to the provisions

of the discovery code and the defense was not excused from providing

timely notice of his testimony. This assignment of error is denied.

¶ 26 In his fifth assignment of error, Appellant

complains the admission of several pieces of evidence denied him a

fair trial. Initially, he contends the exhibition of Robert Hines'

wounds was irrelevant, inflammatory and unnecessarily prejudicial.

At the conclusion of Hines' direct examination, the prosecutor asked

Hines to show the jury the burns he suffered as a result of the

firebombing. Defense counsel objected arguing such a demonstration

was highly prejudicial and the prejudicial impact outweighed any

probative value. The objection was overruled and Hines' removed his

shirt revealing the burns to his arm.

¶ 27 Initially, Appellant has waived any claim

the evidence was not relevant. When a specific objection is raised

at trial, this Court will not entertain a different objection on

appeal. Mitchell v. State, 884 P.2d 1186, 1197 (Okl.Cr.1994), cert.

denied, 516 U.S. 827, 116 S.Ct. 95, 133 L.Ed.2d 50 (1995).

Therefore, we review only the objection as to prejudice. On appeal,

the burden of establishing prejudice is upon the defendant. Woodruff

v. State, 846 P.2d 1124, 1135 (Okl.Cr.), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 934,

114 S.Ct. 349, 126 L.Ed.2d 313 (1993). In reviewing the prejudicial

impact of photographs this Court has said that “[w]here the

probative value of photographs or slides is outweighed by their

prejudicial impact on the jury that, is the evidence tends to elicit

an emotional rather than rational judgment by the jury then they

should not be admitted into evidence.” President v. State, 602 P.2d

222, 225 (Okl.Cr.1979). See also Oxendine v. State, 335 P.2d 940,

942 (Okl.Cr.1958). Applying that standard to this case, the

demonstration of Hines' wounds was not such as to elicit an

emotional rather than rational judgment from the jury. Hines was

burned on the left side of his body-ear, neck and arm. Most of the

scarring resulting from the burns was visible prior to Hines

removing his shirt. The scarring was a direct result of Appellant's

actions and probative of his intent to kill Hines and the others.

The brief display of the wounds was not a mere theatrical

demonstration, but helped the jury in understanding the commission

of the offense. Gilbert, 951 P.2d at 121. Further, there is no

requirement that the visual effects of a particular crime be down

played by the State. McCormick v. State, 845 P.2d 896, 898

(Okl.Cr.1993). Here, the exhibition of Hines' wounds was probative

and that probative value was not outweighed by their prejudicial

impact. Appellant has failed to meet his burden of prejudice, and

the display of the wounds was proper.FN4

FN4. Appellant makes an additional argument that

in showing his wounds to the jury, Hines in effect became an

“exhibit” for the prosecution. He further argues the State did not

memorialize for appellate review what was shown to the jury. He

claims the State thereby violated Rule 2.2(b), Rules of the Oklahoma

Court of Criminal Appeals, Title 22, Ch.18, App. (1998) and the

in-court demonstration was per se inadmissible. The record reflects

the display of Hines' wounds was not offered or marked as an exhibit

by the State. Further, the display of his wounds was no different

than when a witness makes an identification at trial and it is so

noted in the record. Therefore, we find the demonstration was not

per se inadmissible.

¶ 28 Appellant next complains about the admission

of items retrieved from a search of his motel room. On the day

Appellant surrendered to the police, a search warrant was executed

on his motel room. Recovered in the search was a yellow note pad

with several diary entries concerning the state of Appellant's

relationship with Brenda Gardner, an empty plastic cola bottle, two

plastic cola bottle caps, one plastic cola bottle cap liner, and a

full bottle of lighter fluid. The admission of the evidence drew no

objection from defense counsel. Now on appeal, Appellant argues none

of these items were relevant. Reviewing this claim for plain error

only as the claim was not raised at trial, we find the evidence

properly admitted. The diary notes were relevant in showing

Appellant's intent to kill Brenda, and the other evidence, shown by

other testimony to be components of a firebomb, showed Appellant's

ability and opportunity to make a firebomb.

¶ 29 Further, Appellant complains about the

admission into evidence of the actual search warrant and the

accompanying affidavits. Again, they were admitted at trial with no

objection from the defense, therefore we review only for plain

error. We find the information in the affidavit and search warrant

was merely cumulative to other evidence already before the jury.

Appellant has failed to show that he was prejudiced by the admission

of the affidavit and search warrant. We find their admission did not

deny Appellant a fair trial.

¶ 30 Appellant further asserts the State failed

to prove any nexus between himself and the drawings on the jail cell

wall. Appellant objected to the admission of State's Exhibits 33 and

34, photographs of the drawings, on the grounds of authenticity and

relevance. This objection has preserved the issue for appellate

review.

¶ 31 The photographs were introduced during the

testimony of Detective Easley. He identified State's Exhibits 33 and

34 as photographs he took of the drawings on the cell wall. This

testimony was sufficient to authenticate the photographs. 12

O.S.1991, § 2901. As for the relevance of the photographs, Jay Brown

testified that he observed Appellant write derogatory comments and

threats about Brenda G. on the cell walls next to the pictures.

Neither Brown nor any other witness testified to seeing the actual

drawing of the pictures on the wall. Despite this fact, the drawings

corroborated Brown's testimony that Appellant wrote the obscene

comments and threats. Further, the fact that Appellant wrote the

derogatory comments next to the pictures makes it more probable that

Appellant drew the pictures. See 12 O.S.1991, § 2401. This probative

value of the pictures was not substantially outweighed by any

prejudice inherent in the crude nature of the pictures. Accordingly,

we find no error in the admission of the photographs of the

drawings.

¶ 32 Appellant raises an additional challenge to

the evidence in his sixth assignment of error. He asserts the

admission of the statement by David Davis to Detective Burke that

Appellant was not wearing socks when Davis picked him up and

accompanied him to the police station to surrender violated his

rights of confrontation as well as his right to a fair trial and a

reliable sentencing. This testimony was not met with an objection.

Reviewing only for plain error, we find none. When alleged hearsay

is admitted without objection, the statements may be considered as

though they are admissible. Plantz v. State, 876 P.2d 268, 279 (Okl.Cr.1994),

cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1163, 115 S.Ct. 1130, 130 L.Ed.2d 1091

(1995); Davis v. State, 451 P.2d 974, 977 (Okl.Cr.1969). Viewing the

statement as properly admitted, Appellant was not denied his

confrontation rights by the admission of the statement as Davis

testified at trial and was subject to cross-examination. The fact

that Davis could not recall whether or not he told Detective Burke

about the socks does not violate the confrontation clause. See

Omalza v. State, 911 P.2d 286, 301 (Okl.Cr.1995). See also United

States v. Owens, 484 U.S. 554, 558, 108 S.Ct. 838, 842, 98 L.Ed.2d

951 (1988). Further, admission of the statement did not deny

Appellant a fair trial or reliable sentencing as the statement was

consistent with other evidence presented by the State: namely

Brown's testimony that Appellant said he used his sock to make the

wick for the firebomb, and that a complete change of clothing,

except for the socks, was found in Davis's car upon Appellant's

surrender. Accordingly, this assignment of error is denied.

¶ 33 In his tenth assignment of error, Appellant

contends the trial court erred in admitting into evidence his

confession. Appellant asserts the State failed to establish through

substantial independent evidence the trustworthiness of the

confession. We review only for plain error as no objection was

raised to the admission of the confession.

¶ 34 A confession is not admissible under

Oklahoma law unless it is supported by “substantial independent

evidence which would tend to establish [its] trustworthiness.”

Fontenot v. State, 881 P.2d 69, 77-78 (Okl.Cr.1994), quoting Opper

v. United States, 348 U.S. 84, 93, 75 S.Ct. 158, 164, 99 L.Ed. 101

(1954). See also Rogers v. State, 890 P.2d 959, 975 (Okl.Cr.1995),

cert. denied, 516 U.S. 919, 116 S.Ct. 312, 133 L.Ed.2d 215 (1995).

This standard does not require that each material element of the

charged offenses be corroborated by facts independent of the

confession, or that there be no inconsistencies whatsoever between

the facts proven and the facts related in the confession. Id. The

State in the present case did provide sufficient, corroborative

evidence independent of Appellant's confession to show its

trustworthiness and thus its competence.

¶ 35 Tammy Gardner and Robert Hines testified to

seeing Appellant light the firebomb and throw it through the patio

door. Hines was struck and burned by the firebomb. As rescue

personnel arrived at the burning apartments, Appellant was no where

to be found. When Appellant finally surrendered, no socks were found

among an otherwise complete change of clothes. Material necessary to

make a firebomb was found in Appellant's motel room. This evidence

sufficiently corroborates Appellant's confession to Brown as to

render the confession trustworthy and therefore admissible.

¶ 36 Appellant directs our attention to certain

inconsistencies between the confession and the evidence, i.e. no

evidence of an accelerant or a firebomb was found anywhere in the

Gardner apartment, the firebomb was thrown through the closed plate

glass of the patio door, and Hines denied any intimate involvement

with Brenda Gardner. While these inconsistencies were by no means

inconsequential, we do not believe they rendered Appellant's

confession untrustworthy and incompetent. Unless inconsistencies

between the confession and the other evidence so overwhelm the

similarities that the confession is rendered untrustworthy, it

remains within the province of the jury to determine whether the

confession is credible. Fontenot, 881 P.2d at 79. After reviewing

Appellant's confession, the independent corroborative evidence and

the alleged inconsistencies, we find that his confession was

trustworthy. Accordingly, it was competent evidence for the jury to

consider and we find no error in its admission. This assignment of

error is denied.

¶ 37 In his twelfth assignment of error,

Appellant contends the trial court erred in admitting evidence that

several months before the apartment fire, he had threatened to throw

gasoline on and burn Marjorie Long, Brenda Gardner's mother.

Appellant calls this evidence other crimes evidence for which no

notice was given and for which no exception exists. He further

argues that any relevance the evidence may have had was

substantially outweighed by its prejudicial nature.

¶ 38 To support its theory that Appellant

attempted to kill Hines, Brenda Gardner and her family, the State

presented evidence of the tumultuous relationship between Appellant

and Gardner. This evidence included Appellant's threats to harm

Brenda and her family; the threat that “heads would roll” as a

result of Brenda refusing to take full responsibility for their

joint shoplifting charge; his threat to Janet Gardner, Brenda's

sister, that Brenda had better meet him at a certain time and place

or “something bad was going to happen”; Brenda's fear that Appellant

would beat her up; and the threat made to Keith Partain by Appellant

that although he only had twenty cents, he was going to buy a bottle

full of gasoline to make a firebomb so he could burn up Brenda and

her family.

¶ 39 In addition to this evidence, the State also

offered the testimony of Marjorie Long that Appellant forced her car

from the road in an attempt to get Brenda out of Long's car and into

his car. Long testified that Appellant threw rocks at her car and

tried to run her off the road. He eventually forced them to pull

into a restaurant parking lot and told Brenda to get out of the car.

When she refused, Appellant threatened to “get some gas and pour it

on your mother and set her on fire.” Defense counsel objected to

this testimony on the basis that the trial court had previously

ruled that no evidence of threats to anyone other than Brenda

Gardner was admissible. After an in-camera discussion, the trial

court explained that in its previous ruling, the court had held

inadmissible evidence of threats made by Appellant to his ex-wife

and other women he had been involved with before Brenda Gardner. The

trial court further explained that the threats to throw gasoline on

and burn Mrs. Long were not included in the above ruling as that

threat was directed at Brenda Gardner, not Mrs. Long or any other

third party.

¶ 40 The evidence of Appellant's threat to burn

Mrs. Long was included in the State's Notice of Intent to Use

Evidence of Other Crimes or Bad Acts. (O.R.340). The evidence of

Appellant's prior threats toward Brenda Gardner and her family was

relevant to prove Appellant's motive and intent to firebomb the

apartment where Brenda lived. Evidence of previous altercations

between spouses is relevant to the issue of intent. Hooker v. State,

887 P.2d 1351, 1359 (Okl.Cr.1994). Although Appellant and Brenda

were not husband and wife, in light of their close relationship the

evidence was properly admitted pursuant 12 O.S.1991, § 2404(B) and

its probative value outweighed any prejudicial effect. This

assignment of error is denied.

FIRST STAGE JURY INSTRUCTIONS

¶ 41 Appellant contends in his third assignment

of error that his due process rights were violated when the trial

court failed to properly instruct the jury on the intent element of

attempting to kill. Specifically, he argues: 1) the doctrine of

transferred intent does not apply to attempt crimes; 2) Instruction

No. 11 contained inconsistent and confusing language, and

contradicted Instruction No. 10; and 3) the combined effect of

Instructions No. 10 and 11 removed the State's burden of proof on an

essential element of the offense.

¶ 42 Jury Instruction No. 10 provided: In Counts

2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 the defendant is charged with the crime of Attempt

to Kill Another, on or about the 8th day of January 1995, in

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma. No person may be convicted of an attempt

to kill another unless the State has proved beyond a reasonable

doubt each element of the crime. These elements are: First, an

attempt to kill; Second, another person; Third, by performing an act;

Fourth, with the intent to cause or belief that it would cause death.

(O.R.991). This instruction tracks the language of Instruction No.

4-8, OUJI-CR (2d). Instruction No. 11 provided: If you find that the

defendant intended to kill any of the named victims, those being:

Brenda Gardner, Robert Hines, Tammy Gardner, Chase Hacket or Robert

Gardner, and by mistake or accident injured or assaulted any one of

the named victims, the element of intent is satisfied even though

the defendant did not intend to kill any one of the victims. In such

a case, the law regards the intent as transferred from the original

intended victim to the actual victim. (O.R.992). This instruction

tracks the language of Instruction No. 4-11, OUJI-CR (2d).

¶ 43 Appellant objected to Instruction No. 11 at

trial arguing that it was a misstatement of the law. Appellant

further argued “[b]ut when you have the charge of assault and

battery with intent to kill, then there must be a specific intent to

kill an individual. And I don't believe, Your Honor, that they can

clothe that in general terms that intent to kill any is intent to

kill all.” (Tr. V, 81). The trial court overruled this argument

finding the instruction a proper statement of the law.

¶ 44 Under the doctrine of transferred intent

when one person acts with intent to harm another person, but because

of a bad aim he instead harms a third person who he did not intend

to harm, the law considers him just as guilty as if he had actually

harmed the intended victim. W.LaFave and A. Scott, Criminal Law, §

3.12(d) (2nd ed.1986). This Court has not specifically ruled on

whether this doctrine applies in attempt crimes, i.e., situations

where there is no injury to any unintended victim. However, we have

applied the law of transferred intent in a case of assault with a

dangerous weapon, despite the lack of any injury to an unintended

victim. Jones v. State, 508 P.2d 280, 282 (Okl.Cr.1973). In the

present case, when Appellant intended to cause, or believed that the

firebombing would cause the death of one or more of the inhabitants

of Apartment 127, then through his act of attempting to kill any of

those inhabitants by throwing the firebomb at the apartment, he

committed the offense of attempt to kill as to any other persons

assaulted by mistake or accident. Therefore, we find the doctrine of

transferred intent applies in the present case.

¶ 45 In this case, there were multiple victims of

the attempt to kill charges. In Instruction No. 11, the trial court

attempted to comply with the uniform jury instruction by listing the

names all of those individuals in the apartment at the time of the

firebombing as intended victims and using the reference “any one of

the named victims” for the reference to the actual victims. At first

glance, this instruction is confusing as it seems to list the same

individuals as intended victims and actual victims. However, when

the instruction is read in its entirety it is clear that the list of

intended victims is set forth in the disjunctive. Further, the last

sentence of the instruction distinguishes between “the original

intended victim” and “the actual victim.” Therefore, the instruction

reads that if the jury found Appellant intended to kill any of those

persons inside the apartment, those persons being Brenda Gardner,

Robert Hines, Tammy Gardner, Chase Hacket or Robert Gardner, and by

mistake or accident injured or assaulted Brenda Gardner, Robert

Hines, Tammy Gardner, Chase Hacket or Robert Gardner, the element of

intent is satisfied even though Appellant did not intend to kill any

one of the actual victims. Contrary to Appellant's argument, a

rational juror would not have read the instruction as transferring

intent from, for example Robert Hines to Robert Hines. The

instruction, while it could have been more clear based on the facts

of this case, adequately distinguished the intended victim from the

actual victim.

¶ 46 Further, Instruction No. 11 did not negate

the intent element set forth in Instruction No. 10. The burden of

proof set forth in Instruction No. 10 was that the act was performed

with the intent or belief that the act would cause death to another

person. Instruction No. 11 merely provided the intent to kill as to

one person is sufficient to convict as to another person actually

harmed. The burden of proof was not diminished by Instruction 11.

Nor was an element of the offense negated by applying the burden of

proof set out in Instruction No. 10 to the harm caused to a third

person who was the actual victim of Appellant's proven intent.

¶ 47 Having thoroughly reviewed Appellant's

challenges to Instructions No. 10 and 11, we find no errors

warranting reversal. This assignment of error is denied.

¶ 48 In his thirteenth assignment of error,

Appellant contends the trial court erred in failing to give a jury

instruction, sua sponte, requiring corroboration of his confession.

We review only for plain error as no such instruction was requested

nor was an objection raised to the absence of the instruction. We

agree the trial court erred in failing to give an instruction

requiring corroboration of the confession by independent evidence.

Shelton v. State, 793 P.2d 866, 876 (Okl.Cr.1990). However, the

failure to give such an instruction is not grounds for reversal when

the record contains corroborating evidence. Id. As discussed above,

the record in this case contained ample evidence corroborating the

confession. Therefore, we find reversal is not warranted by the

absence of the instruction.

¶ 49 Appellant also contends the trial court

failed to give an instruction, sua sponte, on the need for

corroboration of Brown's informant testimony. Once again we review

only for plain error as no such instruction was requested nor was an

objection raised to the absence of the instruction.

¶ 50 The decision to give a cautionary

instruction is more often discretionary than it is fundamental.

Wilson v. State, 756 P.2d 1240, 1243-44 (Okl.Cr.1988). Here, we find

the trial court did not abuse its discretion in failing to give such

an instruction. Substantial evidence, other than Brown's testimony,

placed Appellant at the scene of the crime. Cf. Smith v. State, 485

P.2d 771, 773 (Okl.Cr.1971) (failure to give cautionary instruction

on informant's testimony reversible error as informant's testimony

was only evidence which placed defendant at the scene of the crime).

Further, the jury was generally instructed on the weight and

credibility to be accorded the witnesses' testimony. (O.R.1001).

Accordingly, we find the absence of a cautionary instruction on

informant testimony did not deny Appellant a fair trial, and this

assignment of error is denied.

SECOND STAGE ISSUES

¶ 51 In his second assignment of error, Appellant

argues the victim impact evidence introduced in this case violated

the rules of evidence and his rights under the Sixth, Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and Article

II, §§ 7 and 9 of the Oklahoma Constitution. Specifically, he

asserts: 1) the testimony of Kiyoka Yamamoto far exceeded the scope

of permissible victim impact evidence; 2) the admission of a live

picture of the victim was error; 3) the admission of a newspaper

article about the victim was hearsay and outside the scope of

permissible victim impact evidence; 4) the victim impact evidence in

this case violated Appellant's right to due process, a reliable

sentencing proceeding and confrontation; and 5) victim impact

evidence has no place in Oklahoma's sentencing scheme.

¶ 52 Victim impact evidence is constitutionally

acceptable unless “it is so unduly prejudicial that it renders the

trial fundamentally unfair.” Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 825,

111 S.Ct. 2597, 2608, 115 L.Ed.2d 720, 735 (1991). In Cargle v.

State, 909 P.2d 806, 827-28 (Okl.Cr.1995) we set out the basis the

United States Supreme Court utilized to find the Eighth Amendment is

not violated by victim impact evidence and that the Fourteenth

Amendment has the potential to be implicated if appropriate

restrictions are not placed on victim impact evidence.

¶ 53 This Court has held victim impact evidence

admissible as long as it is “restricted to the ‘financial, emotional,

psychological, and physical effects,’ or impact, of the crime itself

on the victim's survivors; as well as some personal characteristics

of the victim.” Ledbetter v. State, 933 P.2d 880, 889-90 (Okl.Cr.1997).

The statutory language [22 O.S.Supp.1993, § 984]

is clear the evidence should be restricted to the “financial,

emotional, psychological, and physical effects,” or impact, of the

crime itself on the victim's survivors; as well as some personal

characteristics of the victim. (cite omitted). So long as these

personal characteristics show how the loss of the victim will

financially, emotionally, psychologically, or physically impact on

those affected, it is relevant, as it gives the jury “a glimpse of

the life” which a defendant “chose to extinguish,” (cite omitted).

However, these personal characteristics should constitute a “quick”

glimpse, (cite omitted), and its use should be limited to showing

how the victim's death is affecting or might affect the victim's

survivors, and why the victim should not have been killed. Cargle,

909 P.2d at 828.

¶ 54 In the present case, the State filed a

Notice of Victim Impact Statement. The author of the statement was

Kiyoka Yamamoto, the victim's mother. Mrs. Yamamoto was the last

witness called for the State in the penalty phase of trial. Prior to

her testimony, the trial court noted it had read Mrs. Yamamoto's

statement and found it to be in conformity with Cargle. The court

was informed that Mrs. Yamamoto, a Japanese citizen, would read her

statement in Japanese then it would be translated into English by an

interpreter. Defense counsel agreed to the procedure and noted that

the defense had had a copy of Mrs. Yamamoto's statement for awhile

and agreed that it substantially complied with the law. Mrs.

Yamamoto's statement, which comprised approximately six pages in the

trial transcript, told how she had received a telephone call at her

home in Kyoto, Japan, telling her of her son's injuries and that she

immediately flew to Oklahoma City to be with him. Mrs. Yamamoto said

the victim was her only child that she had raised by herself. She

described her ill health over the last fifteen years and that she

had battled her illness for her son's sake. She described how when

her health was stabilized, her son told her he wanted to go to

America and study. Putting aside her own fears, she agreed to let

her son go to America. Mrs. Yamamoto said her son was an excellent

student and received many awards. She said he wanted to stay in

America and study but worried about his ailing mother. Mrs. Yamamoto

said she and her son talked on the telephone every two or three days

and he came to Kyoto every summer to check on her health.

¶ 55 Mrs. Yamamoto also stated that approximately

one week before her son was killed he told her that if anything

happened to him, to bury him in Oklahoma. She described her last

conversation with her son wherein he told her his downstairs

neighbors were very noisy and made it difficult for him to study.

Fourteen hours after that conversation, she received word that her

son had been injured and had only approximately fifteen hours to

live. Stating that she “could not understand why this was going on

... my heart was screaming, why, why, why ... [m]y head was hit by

big hammer.” She said that all she could think to do was to get an

airplane ticket. She said that reservations were made for her and

she left immediately. “The airplane was so slow. I couldn't eat or

sleep. I could only pray to God not to take my healthy young man's

life.” When she arrived in Oklahoma City, Mrs. Yamamoto rushed to

the hospital and found her son burned over 98 percent of his body.

She said she believed her son heard her voice, that he tried to move

his head and shortly thereafter passed away.

¶ 56 Mrs. Yamamoto said that her son had been

told by Mrs. Tohgi, the person who had made the phone call to Mrs.

Yamamoto and made her flight arrangements, that his mother was on

the way. She said her son squeezed Mrs. Tohgi's hand as tears ran

down his cheeks. Mrs. Yamamoto said that after she talked with her

son his condition changed quickly, and she believed that after he

heard her voice he quit fighting and seemed to be telling her “I

waited for you, ... I'm glad to hear your voice, ... please let me

rest.” Mrs. Yamamoto closed with noting it had been two years and

three months since her son was killed and that his death had greatly

affected her health. She said she had been hospitalized many times

for heart problems since his death. She added that anytime she sees

fires, bombs or emergencies on television, memories of her son's

death return causing her tremendous stress.

¶ 57 It was not until the close of Mrs.

Yamamoto's testimony that defense counsel objected to the victim

impact evidence and requested a mistrial. Defense counsel argued

that Mrs. Yamamoto was very emotional and that he did not realize

how emotional the evidence would be prior to it being presented at

trial. The trial court admitted the evidence was emotional, noting

that the witness cried and that she was permitted a few minutes to

regain her composure. The court noted however that the witness got

through her testimony, and that it was still of the opinion the

evidence was proper under Cargle. The request for a mistrial was

overruled.

¶ 58 The victim impact evidence in this case

comes very close to weighting the scales too far on the side of the

prosecution by so intensely focusing on the emotional impact of the

victim's loss. Id at 826. However, as we stated in Cargle, In

discussing this, we in no way hold the emotional impact of a

victim's loss is irrelevant or inadmissible; we simply state that,

in admitting evidence of emotional impact, especially to the

exclusion of the other factors, a trial court runs a much greater

risk of having its decision questioned on appeal.... The more a jury

is exposed to the emotional aspects of a victim's death, the less

likely their verdict will be a “reasoned moral response” to the

question whether a defendant deserves to die; and the greater the

risk a defendant will be deprived of Due Process.(citation omitted).

909 P.2d at 830.

¶ 59 Mrs. Yamamoto's statements concerning her

feelings and actions upon learning of her son's injury and

subsequent death were emotional, but fell within the guidelines set

forth in Cargle and § 984. These statements were probative of the

emotional, psychological, and physical effects she experienced as a

result of the death of her only child. Mrs. Yamamoto's statements

concerning her son's desire to study in America, his eventual

achievement of that goal and his concern for his mother provided a

brief glimpse of the unique characteristics of the individual known

as Ken Yamamoto. While her statements concerning her fifteen year

illness, her son's wish to be buried in Oklahoma City, and her son's

death bed thoughts upon seeing his mother were not relevant victim

impact evidence,FN5 their admission did not prevent the jury from

fulfilling its function in the second stage of trial. While a

portion of the victim impact testimony was very emotional, taken as

a whole, the testimony is within the bounds of admissible evidence,

and its focus on emotion did not have such a prejudicial effect or

so skew the presentation as to divert the jury from its duty to

reach a reasoned moral decision on whether to impose the death

penalty. Hooper v. State, 947 P.2d 1090, 1105 (Okl.Cr.1997).

FN5. Appellant challenges the admissibility of

Mrs. Yamamoto's statements concerning her son's death bed thoughts

and wishes for burial on the grounds of hearsay. We do not reach

this issue as we find such statements were not probative of the

financial, emotional, psychological, and physical effects, or

impact, of the crime itself on the victim's survivors or personal

characteristics of the victim. Cargle, 909 P.2d at 828.

¶ 60 At the close of Mrs. Yamamoto's testimony,

the State introduced a pre-mortem photograph of the victim. Defense

counsel's objection to the photograph was overruled. This Court has

held such photographs are generally inadmissible, again based on

their relevancy to the issues presented at trial. Cargle, 909 P.2d

at 830. We see no reason to retreat from that ruling. The photograph

was clearly irrelevant as it in no way showed the financial,

psychological or physical impact on the survivors or any particular

information about the victim. The photograph did not demonstrate any

“information about the victim” and it does not show how his death

affected or might affect the survivors. However, this error is

subject to the harmless error analysis. Id. at 835. See also Darks

v. State, 954 P.2d 152, 164 (Okl.Cr.1998). In light of our following

discussion that sufficient evidence to support the aggravating

circumstances was presented and the evidence in support of said

circumstances outweighed the mitigating evidence, the error in

admitting the pre-mortem photograph is harmless beyond a reasonable

doubt.

¶ 61 The State also admitted an article from the

Oklahoma City University campus newspaper concerning the victim and

his achievements at the university as an art student. This exhibit,

State's Exhibit No. 81, was admitted by stipulation. As counsel did

not raise any objection to the exhibit at trial, he has waived all

but plain error review. Simpson v. State, 876 P.2d 690, 698-99

(Okl.Cr.1994). We find no plain error in the admission of the

newspaper article as it did not impact the foundation of the case or

take from Appellant a right essential to his defense. Id.FN6

FN6. Contained in the newspaper article were

comments by friends and professors of the victim describing the

victim's accomplishments and personal characteristics. Title 22

O.S.Supp.1993, § 984.1 restricts those who may give victim impact

evidence to members of the victim's family or someone designated by

the family. Section 984.1 states in pertinent part:A. Each victim,

or members of the immediate family of each victim or person

designated by the victim or by family members of the victim, may

present a written victim impact statement or appear personally at

the sentence proceeding and present the statements orally.... Title

22 O.S.Supp.1993, § 984 defines members of the immediate family as

“spouse, a child by birth or adoption, a stepchild, a parent, or a

sibling of each victim.” None of the individuals interviewed in the

newspaper article met the above criteria. However, it is not

necessary for us to address the merits of the content of the

newspaper article as defense counsel's stipulation to its admission

makes any error in its admission harmless.

¶ 62 Finally, Appellant argues that victim impact

evidence has no place in Oklahoma's death penalty scheme as our

statutes require a balancing test of aggravating circumstances and

mitigation and victim impact evidence is relevant to neither. He

argues that victim impact evidence operates as irrelevant, improper,

highly charged, emotional evidence which is present in every capital

case and has the same effect as an unconstitutionally broad

aggravating circumstance or “superaggravator.” This argument has

been repeatedly rejected by this Court. Cargle, 909 P.2d at 824-30.

See also Conover v. State, 933 P.2d 904, 922 (Okl.Cr.1997); Smith,

932 P.2d at 537. Appellant has not persuaded us to reconsider the

issue.

¶ 63 Having reviewed Appellant's allegations

concerning victim impact evidence, we find he was not denied a

reliable sentencing proceeding by the admission of the victim impact

evidence. Accordingly, this assignment of error is denied. ¶ 64 In

his ninth assignment of error, Appellant contends he was denied a

fair sentencing proceeding by the admission of evidence supporting

the “continuing threat” aggravator. During the second stage of trial,

the State introduced victim protection orders from three different

women issued against Appellant. Appellant filed a motion in limine

to prohibit their admission arguing that the documents were filled

with hearsay and were only used to bolster the witnesses' testimony.

The trial court overruled the objection, finding that as long as the

sponsoring witness testified the orders were properly admissible.

Appellant did not renew his objection when the exhibits were offered

into evidence.

¶ 65 A ruling on a motion in limine is merely

advisory and not conclusive. To properly preserve the issue

contained in such a motion, the proposition must be introduced at

trial, and if overruled, objections should occur at that time.

Conover, 933 P.2d at 912. Appellant's failure to object to the

admission of the exhibits when they were offered waives all but

plain error. We find no plain error.

¶ 66 Appellant further argues the testimony of

witness Troi Billy far exceeded the scope of the More Definite and

Certain Statement of Allegations Set Forth in the Bill of

Particulars. In that pleading the State notified the defense of Troi

Lyn Billy's testimony in support of the “continuing threat”

aggravating circumstance. In the notice the prosecution stated: Troi

Lyn Billy will testify that in July 1991, the defendant threatened

to kill her and her children. She filed police reports in Case

Numbers 9102458, 9102407, 9102474, 9102466 and 9102694. In August of

1991, she filed for a Victim Protective Order. On July 29, 1991, the

defendant pointed a gun at her, her children and Susan Short and

threatened to kill them. On August 9, 1991, defendant telephoned Ms.

Billy and told her “it's time to die for real now, bitch.” On July

13, 1991, Short telephoned Ms. Billy and told her “your fucking ass

is dead.” (O.R.472).

¶ 67 Appellant now complains that Billy's

testimony exceeded the notice when she testified: 1) her house had

been burglarized and when she confronted Appellant he said “I told

you I'm going to get you”; and 2) Appellant once told her he would

cut her head off and “rape her in the ass.”

¶ 68 As to testimony concerning the burglary,

Appellant's only objection at trial was on the grounds of a leading

question. By objecting on that ground alone, he waived all other

grounds, including lack of notice. Mitchell, 884 P.2d at 1197. As

for the testimony concerning the rape threat, Appellant did object

on grounds of lack of notice but not until after Ms. Billy had

testified. This Court remains committed to the general rule that a

timely objection must be made on the record to preserve any alleged

error for appellate review. Wood v. State, 748 P.2d 523, 525 (Okl.Cr.1987).

A timely objection brings the alleged error to the attention of the

trial court and provides an opportunity to correct the error at

trial. Davis v. State, 753 P.2d 388, 392 (Okl.Cr.1988). Reviewing

only for plain error, we find none. The police reports concerning

each incident testified to by Ms. Billy and referenced in the More

Definite and Certain Statement had been provided to the defense.

This was sufficient notice of the State's intent to use evidence of

the burglary and rape threat to support the “continuing threat”

aggravator. As such, Ms. Billy's testimony did not exceed the scope

of the More Definite and Certain Statement. This assignment of error

is denied.

¶ 69 In his fourteenth assignment of error,

Appellant contends that all three aggravating circumstances found by

the jury failed to perform the narrowing function required by the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution

and by Art. II, §§ 7 and 9, of the Oklahoma Constitution. Appellant

recognizes this Court has previously rejected attacks on the

constitutionality of these aggravators, but asks us to reconsider

our decisions. We are not persuaded to alter our prior positions.

Therefore, Appellant's argument is denied as it pertains to the

constitutionality of the aggravating circumstances of “continuing

threat” ( See Hamilton v. State, 937 P.2d 1001, 1012 (Okl.Cr.1997));

“great risk of death” ( See Id.), and “especially heinous, atrocious

or cruel.” ( See Id.).

¶ 70 Appellant also challenges the use of

Instruction No. 4-74, OUJI-CR (2d).FN7 He contends that instead of

limiting the aggravating circumstance of “continuing threat”, the

instruction actually broadens its application by leaving out any

reference to violence. A review of the instruction does not support

Appellant's argument. The first paragraph of the instruction

explicitly refers to the allegation that there exists a probability

that the defendant will commit future acts of violence. That the

subsequently listed two criteria which must be proven do not mention

violence does not negate the burden on the State to prove a

probability that the defendant will commit future acts of violence

that constitute a continuing threat to society as listed in the

first paragraph. Reading the instruction in its entirety, it is

clear the State had the burden of proving the defendant had a

history of criminal conduct that would likely continue in the future

and that such conduct would constitute a continuing threat to

society. Accordingly, we reject Appellant's challenge to Instruction

No. 4-74, OUJI-CR (2d). This assignment of error is therefore denied.

FN7. OUJI-CR 4-74 provides:The State has alleged

that there exists a probability that the defendant will commit

future acts of violence that constitute a continuing threat to

society. This aggravating circumstance is not established unless the

State proved beyond a reasonable doubt: First, that the defendant's

behavior has demonstrated a threat to society; and Second, a

probability that this threat will continue to exist in the future.

ISSUES RELEVANT TO BOTH STAGES OF TRIAL

PROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT

¶ 71 In his seventh assignment of error,

Appellant contends that prosecutorial misconduct in both stages of

trial so infected the proceedings with unfairness as to deny his

constitutional right to a fair trial and reliable sentencing.

Appellant cites to numerous instances during both stages of trial in

which he contends the prosecutors exceeded the bounds of proper

prosecutorial advocacy. Initially, Appellant claims that in the

first stage closing arguments, the prosecutors: 1) indicated they

knew things that the jury did not; 2) misstated the evidence; and 3)

referred to facts not before the jury and to evidence which had been

excluded during trial. None of these comments were met with an

objection at trial. Therefore all but plain error has been waived.

Freeman v. State, 876 P.2d 283, 287 (Okl.Cr.), cert. denied, 513 U.S.

1022, 115 S.Ct. 590, 130 L.Ed.2d 503 (1994).

¶ 72 Reading the entire closing argument in

context, the complained of comments were within the wide latitude of

discussion permitted both the state and the defense in closing

argument. Any misstatements were not so egregious as to have risen

to the level of reversible error. Carol v. State, 756 P.2d 614, 617

(Okl.Cr.1988).

¶ 73 Appellant also asserts the prosecution

allowed Jay Brown to misrepresent his plea agreement with the State.

Appellant argues that what Brown got in return for his testimony

against Appellant was essential in determining his credibility and

that leaving the jury with a false impression of the terms of the

plea agreement violated due process. See Binsz v. State, 675 P.2d

448, 450-51 (Okl.Cr.1984). Brown testified on direct examination

that in exchange for his truthful testimony against Appellant, his

cooperation with the authorities in other drug cases, truthful

testimony against his co-defendant, successful completion of a drug

recovery program and a two week after-care program, and counseling

two to three times a week, he would receive a five year deferred

sentence. On cross-examination, Brown was asked about the meaning of

a deferred sentence. Brown insisted that even if he successfully

completed all of the above requirements he would still have a

conviction on his record, though “it won't be on my record as long

as I don't get in trouble again.”

¶ 74 The plea agreement with Brown indicated that

upon successful completion of the above mentioned requirements and

probationary period, he was to receive a five year deferred judgment.

(State's Exhibit 79). Under Oklahoma law, no conviction results

after the successful completion of the probationary period. 22 O.S.1991,

§ 991(c). Although Brown may not have used the correct terminology

in describing the plea agreement, he clearly testified that in

return for his cooperation and successful completion of the

probationary period, he would no longer have a conviction on his

record. No false impressions of the terms of the plea agreement were

left with the jury.

¶ 75 Turning to the second stage of trial,

Appellant reiterates his complaints about the victim impact evidence

raised in Proposition II and asserts that as the prosecutors in this

case participated in the trial of Cargle v. State, the manner in

which the prosecutors presented the victim impact evidence in this

case was indicative of bad faith and disrespect for this Court. As

discussed previously, the majority of the victim impact evidence was

properly admitted. We find nothing in the record to support

Appellant's claims of bad faith and disrespect for this Court on the

part of the prosecutors. This allegation is denied.

¶ 76 Appellant further argues the prosecutors

improperly: 1) stated that Appellant needed to go to death row for

what he did to the victim's mother; 2) stated that the State does

not seek the death penalty in every case; 3) transformed Appellant's

mitigation evidence into evidence supporting the death penalty; 4)

injected their personal sense of justice into the sentencing

proceeding; and 5) commented on Appellant's decision not to testify

at trial. None of these comments were met with an objection at trial.

Therefore all but plain error has been waived. Freeman, 876 P.2d at

287.

¶ 77 Reviewing the complained of comments in

context, we find the comments were properly based in the law and

were reasonable inferences on the evidence. Any misstatements did

not deny Appellant a fair trial. Addressing specifically the

prosecutor's comments on the mitigating evidence, we find the jury

was not encouraged to ignore the mitigating evidence. Therefore,

Appellant's reliance on Penry v. Lynaugh, 492 U.S. 302, 319, 109

S.Ct. 2934, 2947, 106 L.Ed.2d 256 (1989) and Lockett v. Ohio, 438

U.S. 586, 98 S.Ct. 2954, 57 L.Ed.2d 973 (1978) is misplaced. Here,

the prosecutor simply argued the evidence presented in mitigation

was not persuasive. We find no error in the prosecution's attempt to

minimize the effect of the evidence presented by the defense.

Hamilton, 937 P.2d at 1010-11. Further, the jury was thoroughly

instructed as to the mitigating evidence. The prosecutors' comments

did not prevent the jury from fully considering the evidence

presented in mitigation.

¶ 78 Two other challenged comments warrant our

specific attention. Appellant asserts that by arguing that no

remorse had been shown, the prosecutor improperly commented on

Appellant's failure to testify. We find no error in this comment as

we have repeatedly held that “[b]efore a purported comment at trial

on a defendant's failure to testify will constitute reversible

error, the comment must directly and unequivocally call attention to

that fact.” Gilbert, 951 P.2d at 120; Hampton v. State, 757 P.2d

1343, 1346 (Okl.Cr.1988). The comment here did not directly call

attention to the fact that Appellant did not testify, rather the

comment was properly based upon Appellant's demeanor in the

courtroom.

¶ 79 However, the prosecutor did comment that it

was not justice to allow the defendant three meals a day, a clean

place to sleep, and visits by his friends while the victim's mother

daily grieves for her only son. This type of argument has been

repeatedly condemned by this Court. Le v. State, 947 P.2d 535, 554 (Okl.Cr.1997);

Duckett v. State, 919 P.2d 7, 19, (Okl.Cr.1995). However, under the

evidence in this case, we cannot find the comments affected the

sentence.

¶ 80 “Allegations of prosecutorial misconduct do

not warrant reversal of a conviction unless the cumulative effect

was such [as] to deprive the defendant of a fair trial.” Duckett,

919 P.2d at 19. Because we do not find the cumulative effect of any

inappropriate comments deprived Appellant of a fair trial, this

assignment of error is denied.

INEFFECTIVE ASSISTANCE OF COUNSEL

¶ 81 Appellant contends in his eighth assignment

of error that he was denied a fair trial and reliable sentencing

proceeding by the ineffective assistance of counsel. Specifically,

he contends counsel was ineffective for: 1) failing to promptly

notify the State of a defense witness; 2) failing to object to

hearsay and other patently inadmissible evidence; 3) failing to

request instructions regarding uncorroborated confessions and the

reliability of informant testimony; 4) conceding guilt and

abandoning the entire defense theory in closing argument; and 5)

failing to object to improperly admitted victim impact evidence.

¶ 82 An analysis of an ineffective assistance of

counsel claim begins with the presumption that trial counsel was

competent to provide the guiding hand that the accused needed, and

therefore the burden is on the accused to demonstrate both a

deficient performance and resulting prejudice. Strickland v.

Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 2064, 80 L.Ed.2d 674

(1984). Strickland sets forth the two-part test which must be

applied to determine whether a defendant has been denied effective

assistance of counsel. First, the defendant must show that counsel's

performance was deficient, and second, he must show the deficient

performance prejudiced the defense. Unless the defendant makes both

showings, “it cannot be said that the conviction ... resulted from a

breakdown in the adversary process that renders the result

unreliable.” Id. at 687, 104 S.Ct. at 2064. Appellant must

demonstrate that counsel's representation was unreasonable under

prevailing professional norms and that the challenged action could

not be considered sound trial strategy. Id. at 688-89, 104 S.Ct. at

2065.

¶ 83 When a claim of ineffectiveness of counsel

can be disposed of on the ground of lack of prejudice, that course

should be followed. Id. at 697, 104 S.Ct. at 2069. Concerning the

prejudice prong, the Supreme Court, in interpreting Strickland, has

held: [An appellant] alleging prejudice must show “that counsel's

errors were so serious as to deprive the defendant of a fair trial,

a trial whose result is reliable.” Strickland, 466 U.S., at 687, 104

S.Ct., at 2064; see also Kimmelman v. Morrison, 477 U.S. 365, 374,

106 S.Ct. 2574, 2582, 91 L.Ed.2d 305 (1986) (“The essence of an

ineffective-assistance claim is that counsel's unprofessional errors

so upset the adversarial balance between defense and prosecution

that the trial was rendered unfair and the verdict rendered

suspect”); Nix v. Whiteside, supra, 475 U.S. [157], at 175, 106

S.Ct. [988], at 998[, 89 L.Ed.2d 123 (1986) ]. Thus, an analysis

focusing solely on mere outcome determination, without attention to

whether the result of the proceeding was fundamentally unfair or

unreliable, is defective. To set aside a conviction or sentence

solely because the outcome would have been different but for

counsel's error may grant the defendant a windfall to which the law

does not entitle him. See [ United States v.] Cronic, supra, 466