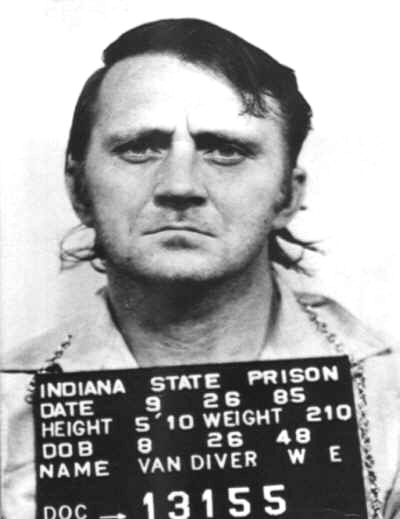

DOB: 08-26-1948

DOC#: 13155 White Male

Lake County Superior Court

Judge James E. Letsinger

Prosecutor: Thomas W. Vanes

Defense: Herb Shaps

Date of Murder: March 20, 1983

Victim(s): Paul Komyatti, Sr.

W/M/62 (Father-In-Law of Vandiver)

Method of Murder: stabbed with

fish filet knife over 100 times

Summary: Paul Komyatti, Sr. on

occasion drank to excess and became loud and violent. He was

disliked by members of his immediate family, which included his wife,

Rosemary, his son Paul Jr., and his daughter , Mariann.

Paul Sr. had demanded that Mariann divorce

Vandiver because of his criminal past., and threatened to inform the

police on him.

Vandiver joined with the family in a conspiracy

to kill Paul Sr. Pursuant to their agreement, several attempts to

poison him were made without success.

Finally, they decided to put him under with ether

and inject air into his veins.

One evening, Vandiver and Mariann waited outside

the home for a signal from Paul Jr. that Paul Sr. was asleep. Upon

seeing the signal, they entered the house and changed the plan at

the last moment for lack of ether. Instead they entered the bedroom

intending to smother Paul Sr., and sprang on him in his bed. Paul

Sr. fought hard for his life and yet another attempt at murder was

bungled.

Vandiver, however, terminated the resistance by

stabbing him in the back with a fish filet knife "at least 100

times." 34 deep knife wounds were later discovered on the body. He

hit him in the head 5 or 6 times with his gun, but he was still

breathing. By Vandiver's own admission, decapitation was the

immediate cause of death.

Vandiver and the other family members then

sectioned up the body while making jokes. Evidence was also

presented that Vandiver had gotten a "loan" of $5000 from Paul Jr.,

as well as $1700 and Paul Sr.'s truck from Rosemary.

At trial, Vandiver recanted his prior confessions

and placed the entire blame on Paul Jr. for the murder and

dissection.

Conviction: Murder

Sentencing: January 20, 1984 (Death

Sentence)

Aggravating Circumstances: b(3)

Lying in wait; b(4) Hired to kill

Mitigating Circumstances: None

VANDIVER WAIVED APPEALS AND WAS EXECUTED BY

ELECTRIC CHAIR ON 10-16-85 AT 12:20 AM EST. HE WAS THE 72ND

CONVICTED MURDERER EXECUTED IN INDIANA SINCE 1900, AND THE SECOND

SINCE THE DEATH PENALTY WAS REINSTATED IN 1977.

Vandiver v. State, 480 N.E.2d 910 (Ind.

July 29, 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Lake County

Superior Court, Criminal Division, James E. Letsinger, J., of murder

and sentenced to death, and defendant expressed a desire not to

appeal sentence or conviction.

The Supreme Court, Pivarnik, J., held

that: (1) examination of defendant indicated he intelligently waived

appeal of conviction, although appeal of sentence could not be

waived; (2) record was sufficient to find that trial court did not

err in the way it imposed death sentence; and (3) record was

sufficient to support sentence of death. Affirmed.

PIVARNIK, Justice.

This case comes directly to this Court since it involves the

imposition of a death sentence pursuant to Ind.Code § 35-50-2-9 (Burns

1985). Defendant-Appellant William Carl Vandiver was charged and

convicted of murder, Ind.Code § 35-42-1-1 (Burns 1985), by a jury in

the Lake Superior Court on December 19, 1983. The same jury

subsequently heard additional evidence presented by the State to

prove certain aggravating circumstances and, after additional

deliberation, recommended to the trial court that the death sentence

be imposed.

The trial court agreed and accordingly sentenced

Vandiver to death. Vandiver then was informed by the trial court of

his right to appeal and Attorney Martin Kinney was appointed to

represent him through the appellate process.

On November 5, 1984, Vandiver notified this Court

by letter that he desired to waive his appeal. This desire and

corresponding request was further substantiated by a verified "Motion

to Waive Appeal" apparently filed pro se by Vandiver on November 8,

1984. In said Motion, Vandiver stated: "4. attached hereto and

incorporated into this motion is a copy of the letter sent to his

attorney, Martin H. Kinney, terminating all defense for the

defendant. 5. that he (William Vandiver) does not want any other

attorneys or legal groups to interfere with this waiver motion."

Vandiver also sent a copy of his "Motion to Waive

Appeal" and a letter dated November 8, 1984, to Attorney Kinney

directing Kinney to cease representing him. We note that Kinney has

filed with this Court at least two sworn affidavits attesting to the

fact that he talked with Vandiver at length on several occasions

about his right to appeal and that each time Vandiver thoughtfully

stated his desire to waive his appeal and to have no one do anything

on his behalf in regard to the mandatory review of his death

sentence.

This Court, of course, faced a similar situation

in 1981 in the case of Stephen Judy. See Judy v. State, (1981) 275

Ind. 145, 416 N.E.2d 95. In Judy, we held that Ind.Code §

35-50-2-9(h) precludes any waiver of a review of the sentencing in a

death penalty case but does not preclude waiver of a review of the

underlying murder conviction. Accordingly, this Court set a hearing

for Vandiver to appear in person before us and accompanied by

Attorney Kinney so that we might determine whether he did, in fact,

wish to waive appeal of his murder conviction and, if so, whether

his waiver was voluntarily and knowingly made.

On January 17, 1985, Vandiver, accompanied by

Attorney Kinney, appeared in person before this Court and was

thoroughly examined by us about his waiver request. At that hearing,

Vandiver very freely and openly discussed his situation. In

particular, he stated that he understood that he had a right to an

appeal with the assistance of counsel, that a review of his

conviction might result in an order for a new trial, and that if he

received a new trial, he would be entitled to a jury, a change of

judge and a change of venue from the county. He further expressed

his understanding that if he were granted a new trial, he would be

entitled to the assistance of counsel and to subpoena witnesses in

his behalf.

In addition, Vandiver stated that he was aware

that a new trial might result in his acquittal while our automatic

review of his death sentence might result in setting it aside and

the imposition of a term of years in prison. Moreover, Vandiver

acknowledged that he understood that a waiver at that time of any

review of his murder conviction would be considered a final decision

and would stand even if this Court were to decide to set aside his

death sentence. Finally, Vandiver freely admitted that he received a

"fair" trial and was guilty of the murder for which he was convicted.

To explain why he desired to waive his appeal, Vandiver stated:

"Well, I turned myself in. I admitted to the

crime. I see no sense in wasting everybody's time. At the best that

could happen, I would end up doing forty-five years, and I'm going

to die there anyway, so why--why prolong it. You know--you know,

there is no need. I'm going to die there regardless, so I don't see

no sense in setting there when it's going to happen anyway.... Well,

to me it [being executed] would be less than getting a tooth pulled.

It would be over with. My family wouldn't have to suffer no more, my

friends or the people that are concerned. It would be over with. I

see no sense in dragging them around for another ten or fifteen

years and have to depend on them. I see no sense in that either ...

I am a gambler; I was *912 taking a gamble. The gamble didn't pay

off. I see no sense to proceed any further with anything."

After observing Vandiver's demeanor in court and

noting his responsiveness to our very thorough questioning, this

Court decided to accept Vandiver's waiver of appeal. This is to say

that we found Vandiver competent to make a waiver and also found

that he knowingly, voluntarily and intelligently waived his right to

appeal his murder conviction. Although Vandiver's appeal was deemed

waived, a question arose regarding whether briefing was necessary to

facilitate our automatic review of Vandiver's death sentence

pursuant to Ind.Code § 35- 50-2-9(h).

This question originally was taken under

advisement but on January 22, 1985, this Court issued an "Order

Setting Briefing." By said Order, we directed the Public Defender of

Indiana to assist us in our consideration of Vandiver's sentencing

in this case. Specifically, the Public Defender was ordered to: "brief

the question of imposition of the death sentence in light of the

statutory requirements of IC 35-50-2-9. Argument shall be confined

to the issue of the death sentence in light of IC 35-50-2-9

Potential errors in connection with the conviction which have been

waived shall not be argued."

We note that Vandiver never requested to be

represented by the Public Defender and, in fact, desired that no one

promote any kind of defense on his behalf. Accordingly, the Public

Defender was engaged by us to insure our best possible review of

Vandiver's death sentence by briefing the narrow question of whether

Vandiver's death sentence comports with the statutory requirements

of Ind.Code § 35-50-2-9.

The Public Defender was to do no more and we

accordingly will disregard those issues and arguments raised by the

Public Defender which are beyond the scope of our specific

assignment to the Public Defender. In this regard, the State's "Motion

To Strike In Part Appellant's 'Death Sentence Review Brief' " is

granted. We note that the Public Defender is now discharged from any

further involvement in this case having completed the briefing

assignment we gave by our Order of January 22, 1985. The Public

Defender is thanked for its service to this Court.

We also note that Martin Kinney was effectively

terminated as Vandiver's attorney by Vandiver's letter to Kinney of

November 8, 1984. Having already decided that Vandiver could and did

waive appeal of his murder conviction, we now find that only two

issues need be considered which are as follows: 1. whether the

procedure by which the death penalty was imposed on Vandiver fully

comports with the dictates of Ind.Code § 35-50-2-9; and 2. whether

death is an appropriate penalty in Vandiver's case according to our

Indiana Rules for the Appellate Review of Sentences.

* * * *

The trial judge presiding over Vandiver's

bifurcated proceeding made very detailed findings to demonstrate his

reasons for making the judgment he did after receiving the jury's

recommendation of death. In particular, the trial court made the

following findings:

"The Court now enters its findings pursuant to

I.C. 35-50-2-9 as follows: For several months prior to the death of

Paul Komyatti, Sr., members of his immediate family: his wife,

Rosemary Komyatti; his son, Paul Komyatti, Jr.; his daughter,

Mariann Vandiver and his son-in-law, [Defendant-Appellant] William

Vandiver, entered into an agreement each with the other with the

criminal objective of killing Paul Komyatti, Sr., an elderly man,

retired because of physical disability with heart trouble.

Motives of each family member were varied.

Rosemary, the wife, was constantly belittled, verbally abused and

made to beg for what money she needed. Paul, Jr., viewed his father

as too strict, not enabling him to spend his money as he wanted and

not enabling him to date socially. He, likewise, was subjected to

periodic loud verbal abuse. Paul, Sr., on occasion drank to excess

and was loud and violent as a result making all present

uncomfortable.

Mariann, the daughter, whose testimony is the

source of much of this family background information, also disliked

her father for the same reasons. Additionally, he demanded she

divorce the defendant because of his prior criminal activity. The

defendant was supposedly wanted by Chicago police for questioning

about another killing. Paul, Sr. had threatened to inform the police

as to their whereabouts.

Their mutual decision to kill Paul, Sr. was

implemented by several attempts to poison his medicine, his coffee,

his food, all of which failed to kill and were aborted because they

were afraid he would consult a doctor to cure his frequent illnesses.

The final decision on the method of his death came on the 19th of

March, 1983, to put him under with ether and inject air into his

veins.

During the late night hours of the 19th and the

early morning darkness of the 20th, the defendant in the company of

Mariann and, unknown to Paul, Sr., waited in concealment outside the

house for the signal from Paul, Jr. that Paul, Sr. was asleep.

Defendant and Mariann, upon seeing the signal flashed,

surrepticiously (sic) entered the house, altered the plan at the

last moment because of the lack of ether and decided to smother him.

The defendant and Paul, Jr. entered the bedroom,

sprang upon Paul, Sr. as he lay sleeping and bungled yet another

execution. The victim fought hard for life, making it impossible to

follow through with asphixiation (sic). The defendant had difficulty

holding Paul, Sr. down even with the help of Paul, Jr. holding his

legs. Paul, Sr. pleaded for his life, saying: 'Son, Son, can't we

work something out?' Calls also went out to his wife to summon the

police and to his grandson for aid, so loud that Mariann closed the

bedroom door lest the grandchild be awakened.

The defendant terminated the resistance by

stabbing Paul, Sr. in the back, in the words of the defendant, 'at

least one hundred times' with a fish filet knife he always carried

in his pocket. Hitting Paul, Sr. over the head five or six times

with his gun, which he also always carried, had little effect. At

this point Paul, Sr. was not yet dead. Certainly a fatal blow had

been struck from which Paul, Sr. would have died but for immediate

surgical intervention.

The actual count of knife wounds was 34 of the

deep penetrating variety. However, he was still breathing as the

defendant began his grisly preparations to dispose of the body. By

the defendant's admission, the decapitation was the immediate cause

of death, but there was no evidence that the victim was conscious at

the time.

In terms of the sentence to be imposed the

sectioning of the body is not so critical as torture of the victim

as it is to show the state of mind of the defendant and his cohorts.

Things like offering Paul, Sr.'s penis to Rosemary as a joke; taking

a smoke break because of the smell and length of the task;

commenting on the toughness of his skin; lecturing Paul, Jr. on the

use of the knife instead of the saw (because saw teeth plug up with

fat and flesh); and commenting casually on the amount of fat around

his heart as like 'a chicken heart' show a callousness of mind of

singular dimension.

Lack of conscience, or a showing of no remorse,

or inhuman feelings are inadequate expressions of the deep disgust

and revulsion experienced by the Court. It is as though all

concerned are humanoids only capable of speech and other indicia of

bodily functions. The Defendant's code of conduct, if any, does not

include familial loyalty that other primate species enjoy at the

lowest level.

It now appears the conspirators were correct as

to the money that would have been available had their plan been

successful. In fact, defendant and his wife had gotten a 'loan' of

five thousand dollars ($5,000) from Paul, Jr. and one thousand seven

hundred dollars ($1,700) from Rosemary plus the victim's truck. It

shows in the most convincing manner that the defendant's prime

motive has been money.

In this respect, the defendant's moral character

is slightly rehabilitated by this most venal of motives. Defendant's

expectation of further monetary gain was the same as any husband of

an heiress to an estate. At trial, defendant recanted his prior

confessions. He placed on seventeen year old Paul, Jr. the entire

blame for the killing and dissection. This does little to

rehabilitate his basic lack of character. It directly contradicts

the other available testimony and physical evidence.

He paints himself as the victim, a pawn of a

demented family ploy, sacrificed in a gambit to save his wife. His

portrait is a caricature, with just enough admissions against his

penal interests to give it the appearance of truth. His admissions

at trial of six separate attempts to murder, three times with

concentrated nitroglycerin tablets, one time with rat poison and one

time with a combination of poison, cocaine and codeine belie his

denial of the only act that succeeded. He had nothing to lose in the

attempt and he has, in fact, lost nothing. This visualization of the

scenario is unworthy of belief and wholly rejected by the Court.

* * * *

In this case, the trial court's findings as set

out above in part I clearly demonstrate that the trial court made an

individualized consideration of Vandiver's crime and of Vandiver's

character. We have reviewed the trial judge's written findings along

with the evidence in the case and find that the record clearly

supports the trial judge's conclusion that the imposition of a death

penalty for Vandiver's murder conviction was justified by the nature

of the offense and by the character of the offender. Moreover, the

evidence supports our conclusion that Vandiver's death sentence was

not arbitrarily or capriciously arrived at and is not manifestly

unreasonable.

The sentence of the trial court is affirmed. This

cause is remanded to the trial court for the sole purpose of setting

a date for Vandiver's death sentence to be carried out.