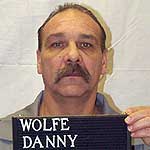

It took 2 ½ years but Danny Wolfe-- who was likely

wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death for the murders of Lena and

Leonard Walters in rural Camden County-- finally has a date for his new

trial. Platte County Judge Gary Witt at the May 27 hearing ordered the

retrial to begin June 5, 2006, with jury selection set for May 15.

The Missouri Supreme Court in February 2003

overturned the murder convictions and death sentences, ruling he had

inadequate representation which failed to independently investigate his

strong claim of innocence.

Judge Witt also ruled favorably for Mr. Wolfe on four

motions and continued to consider his request to change confinement

conditions. Currently, he is locked in his cell 23 hours daily with one

hour available for the shower, exercise yard, telephone for collect

calls and/or to access the law library and his legal papers. Such

confinement, his attorneys assert, could be used by prosecutors during

the trial's sentencing phase as proof to jurors of his dangerousness to

society (even though he has an excellent institutional record)-- one of

many possible “aggravating factors” necessary to justify a death

sentence.

Late last summer, Judge Witt honored Mr. Wolfe's

request and appointed Cyndy Short, an eminently qualified lawyer outside

of the public-defender system to represent him-- but the judge declined

to order state funding for her work on behalf of her indigent client.

Shook, Hardy and Bacon, based out of Kansas City, has thankfully agreed

to assist Ms. Short in preparation for the trial, but won't be paying

for her work as the lead attorney in Mr. Wolfe's defense. Please send

any funds you can to help pay for her essential services.

*****

Reflections from Danny Wolfe's 27 May Platte

County Court Hearing

On Friday morning, May 27, 2005, Platte County Judge

Gary Witt heard several motions presented by Cyndi Short and lawyers

from Shook, Hardy and Bacon on behalf of Danny Wolfe and a few motions

presented as well by Kevin Zoellner an assistant Attorney General in the

case, State of Missouri v. Danny Ray Wolfe.(Mr. Wolfe had lived

under a death sentence for five years after having been convicted of

murdering Lena and Leonard Walters in rural Camden County. The Missouri

Supreme Court in February 2003 overturned his murder convictions and

death sentences, ruling he had incompetent representation which failed

to independently investigate his strong claim of innocence. The court

ordered the county prosecutor to set Mr. Wolfe free or re-try him.)

Perhaps one of the most poignant moments in the

proceeding came very near the end. Attorneys for Mr. Wolfe, the

assistant attorney general and Judge Witt, all concurred his new trial

will begin June 5, 2006 with jury questioning to start two weeks earlier.

On Wednesday afternoon, Mr. Wolfe told the FOR he had

initially hoped a court date would be set early next year, yet he

understands the challenges of trying to mesh the schedules of several

attorneys, the state and court. Indeed he said, it is a relief to have a

concrete trial date finally, after waiting for more than 2 ½ years after

the MO high court's ruling. At last there is light for Danny at end of a

very long tunnel.

The first motion presented at Friday's hearing dealt

with the unconstitutionality of prosecutors having the use of all of Mr.

Wolfe’s papers-- notes from his previous attorneys, personal writings

dealing with the case, notes of trial strategy, and notes from

privileged conversations between Mr. Wolfe and his attorneys. Adam

Moore, an attorney with Shook, Hardy and Bacon (a nationally renowned

law firm which has committed to assist Ms. Short in her defense of Mr.

Wolfe) argued that to allow prosecutors full use of the file would deny

Mr. Wolfe both of his 5th and 6th Amendment rights.

The 5th Amendment guarantees in a criminal case you

cannot be compelled to be a witness against yourself; the 6th Amendment,

among other things, deals with a person’s right to counsel. Mr. Moore

also aptly pointed out, Wolfe’s previous counsel had been deemed by the

Missouri Supreme Court to be so ineffective, as to merit Mr. Wolfe a new

trial. Allowing the prosecution to use the file would seem to yet again

subject Danny Wolfe to previous counsel’s incompetence.

The next issue dealt with by the Court was the

diminished ability of Mr. Wolfe's legal team to speak with witnesses.

Craig Proctor, also with the Shook law firm and representing Mr. Wolfe,

reported that in April their investigator approached Jessica Cox (the

state's star witness in the initial trial, who cooperated with the state

to avoid prison for her part in the murders) to question her.

Before identifying himself, Ms. Cox mistakenly

assumed he was with the FBI, saying she knew he was coming. The

investigator then introduced himself but remained concerned an FBI

investigation may be going on without the awareness of the Defense. Mr.

Zoellner stated that he was unaware of such a federal investigation but

that he had not specifically looked into the matter. Judge Witt ordered

the state to find out if the FBI is indeed investigating this witness

and to make the Defense aware of his findings. The assistant AG agreed

to do so.

Ms. Cox reportedly told the investigator, prosecutors

ordered her not to speak with members of Wolfe's defense team, so she

declined to respond to his questions once she found out his business

affiliation. Both Mr. Zoellner and Mr. Proctor acknowledged that neither

of them were present during the conversation with Ms. Cox.

The attorney for Mr. Wolfe additionally questioned a

contention made by Camden County Prosecutor W.J. Icenogle that defense

attorneys and investigators needed to make an appointment through his

office prior to their meeting with prospective witnesses and that an

attorney for the state needed to be present for any such meeting.

Mr. Proctor asked that the judge write a letter

instructing witnesses that they have the right to talk to defense

attorneys and their investigators with or without the State’s presence.

This letter would also let them know that they do not have to talk to

the Defense. The State argued against such a letter but suggested that

one were written, it should be shown to ALL witnesses (not just the

primary witness discussed above).

Mr. Zoellner filed a motion to quash the requests of

Mr. Wolfe for changes in his confinement. He contended these were issues

which should be determined in federal not state court. The defendant, he

argued, relinquished his right to question his living conditions when he

successfully requested the court move him from the Camden County jail to

the Platte City institution.

Mr. Zoellner further insisted the jail's warden not

he nor the court ought to determine how Mr. Wolfe would be detained. The

only issue for the court to determine was whether Mr. Wolfe was guilty

of murder, according to the assistant Attorney General.

Also representing Mr. Wolfe was Tim Rieman another

Shook attorney. He argued for changes in their client's confinement

conditions, pleading with the court to move him out of what's

essentially solidarity confinement. Currently, he is locked in his cell

for 23 hours each day and allowed one hour out of the cell (which is

about four strides long, the attorney notes).

During that hour, he may have access to a shower, an

exercise yard (which he can't typically use because prisoners from

another housing are scheduled to use it at the same time), to the

telephone for collect calls, and/or to access the law library and his

legal papers.

Mr. Rieman insisted that Mr. Wolfe's current

conditions of imprisonment could have a significantly harmful impact

during the trial's penalty phase, should he again be found guilty of the

murder. Prosecutors could use the fact he was in solitary confinement as

proof to jurors of his dangerousness to society, one of many possible

“aggravating factors” necessary to justify a death sentence.

Previously, while he was in Camden County Jail-- and

even while confined at the maximum-security Potosi Correctional Center,

after being sentenced to death-- Mr. Wolfe had never been housed in such

extremely confining conditions for disciplinary reasons. In his eight

years since his conviction, he has had an excellent institutional record

and has never been the perpetrator nor recipient of violence. There is

no security rationale, the attorney argued, for Mr. Wolfe to be in

solidarity confinement.

Mr. Rieman asserted that Mr. Wolfe has always been an

active participant in his legal defense and knows more about the case at

this point than even do his attorneys-- thus his help and unfettered

access to legal materials, is essential to his ability to assist in his

own defense. The defense attorney argued Mr. Wolfe was moved to Platte

County so that he would be closer to the attorneys working on his case.

He sited the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on May 23,

2005 involving a Missouri prisoner Carmen Deck in which the justices

ruled 7-2 that it is unconstitutional to visibly shackle and handcuff a

defendant in a sentencing proceeding that could lead to the death

penalty unless the shackling is justified by an “essential state

interest”—such as courtroom security—specific to the defendant on trial.

The Court, Mr. Rieman argued, indicated that justice is best served if

defendants are detained by the least restrictive measures possible.

Bruce Tepekian, also an attorney with the Shook law

firm, stated he had tried without success to mediate with Platte County

Sheriff about easing his client's confinement, and approached the Court

only as a last resort. His legal team accepted that such severe

confinement would be acceptable for their client's first month or so in

the jail, as officials reviewed Mr. Wolfe's conduct, but eight months of

solidarity confinement amounted to cruel and unusual punishment.

Mr. Tepekian said the Platte County sheriff told him

his Camden County counterpart claimed Mr. Wolfe was an escape risk and

thus solidarity confinement was prudent. Mr. Tepekian reported however,

when he contacted the Camden County Sheriff, he was told they had only

applied the most extreme security because Mr. Wolfe was charged with

murder, and that after a period of evaluating his behavior, Camden

County officials granted Mr. Wolfe privileges similar to others who were

jailed there.

Another defense attorney said there were five other

individuals in solitary confinement within the Platte County Jail, four

of them for disciplinary reasons. He added that a couple individuals

charged with murder, awaiting trial at the Platte County facility were

not automatically assigned to be locked down for 23 hours each day, as

had their client.

Mr. Tepekian filed a motion as well to obtain a full

list of the state's evidence in its case against Mr. Wolfe. In a trip he

and Ms. Short recently took to Camdenton, he said, they reviewed

documents and found several not previously identified by the state. Full

disclosure was essential, he noted.

Finally, the Court set a date for Danny Wolfe’s new

trial, which Ms. Short predicted could last for three weeks and would

involve calling at least 300 witnesses. Judge Witt agreed to a time line

that all pre-trial motions would need to be filed by March 30 with a

hearing on the motions to take place April 6-7. Potential jurors in

Platte County would be questioned beginning on May 15. The trial would

begin in Camdenton, with attorneys presenting their case to the Platte

County jurors on June 5.

Judge Gary Witt said he would rule on the other

motions within the next few weeks.

-- By Barbara Poe and Jeff Stack

Additional Notes:

Send donations to help support Ms. Short's work on

behalf of Danny Wolfe. Late last summer, Judge Witt honored Mr. Wolfe's

request and appointed as his attorney Cyndy Short, an eminently

qualified lawyer outside of the public-defender system. The judge

however, declined to order state funding for her work on behalf of her

indigent client. Shook, Hardy and Bacon, based out of Kansas City, has

thankfully agreed to assist Ms. Short in preparation for the trial, but

they will not be paying for her work as the lead attorney in Mr. Wolfe's

defense. At this point Ms. Short is basically working pro bono,

practically without compensation (beyond a couple hundred dollars raised

thus far) and will need funds to help support her family, while she

prepares a vigorous, proficient defense of Danny Wolfe.

High court overturns double-murder ruling

Wednesday, February 12, 2003

JEFFERSON CITY(AP) - The Missouri Supreme Court

yesterday overturned the convictions of a man sentenced to death for a

double murder near the Lake of the Ozarks, ruling his attorneys failed

to pursue evidence casting doubt on his guilt.

Danny Wolfe, 52, was found guilty of two counts of

first-degree murder in the killings of Leonard and Lena Walters of

Greenview, who were found dead on Feb. 23, 1997.

Wolfe’s convictions and death sentences had been

upheld by the state’s high court during a standard appeal three years

ago. But in a unanimous decision, the court ruled that Wolfe had

received ineffective assistance from his attorneys.

"This court’s confidence in the fairness of the trial

and the reliability of Wolfe’s conviction is seriously undermined,"

Judge Richard Teitelman wrote for the state’s highest court, which

reversed the convictions and ordered a new trial.

The court said no physical evidence linked the

killing to Wolfe, yet his attorneys had failed to adequately pursue

evidence placing the prosecution’s chief witness, Jessica Cox, at the

murder scene.

Cox - who was given immunity from prosecution -

testified during the 1998 trial that Walters was shot during a

test-drive of a red Cadillac he was offering for sale. Cox said she was

driving the car and Walters was in the passenger seat when Wolfe shot

him from the back seat. She said she then waited outside while Wolfe

went into the couple’s home and killed Lena Walters.

Wolfe’s trial attorneys asserted that Cox was framing

Wolfe. In court, however, they argued only that hair found in the car’s

back seat and in a trash bin was not Wolfe’s, the Supreme Court said.

A post-trial comparison showed the hair fibers

matched Cox. A defense attorney could have easily arranged a scientific

comparison of the hair fibers before the trial, the court said.

"The results of the hair analysis would have likely

cast doubt on Cox’s credibility," Teitelman wrote. "The evidence would

have directly contradicted Cox’s testimony and supported Wolfe’s defense

that Cox was framing him."

Wolfe’s two trial attorneys - public defenders

Kimberly Shaw and Nancy McKerrow - did not immediately return calls to

their Columbia offices yesterday. Shaw is now in private practice, and

McKerrow no longer handles death penalty cases for the public defender’s

office.

Attorney Melinda Pendergraph, who represented Wolfe

before the Supreme Court, said the trial attorneys were led by

prosecutors "to believe that the hair hadn’t really been seized, so they

just dropped the ball on that and didn’t follow up."

The Supreme Court ruling "just scratches the surface

in terms of the unfairness" to Wolfe, she said. "I am really happy he

got a new trial," she said. "There are just a few cases in your career

that you just hope and pray that they’ll get relief, and this is one of

them."

Camden County prosecutor W.J. Icenogle, who handled

Wolfe’s 1998 trial, declined to comment about the Supreme Court ruling.

Intervention Warranted in Danny Wolfe's Case

Coffee with a Dead Man

St. LouisPost-Dispatch Editorial (April 2000)

Robert Morgan had coffee with his friend Leonard

Walters on Thursday morning, Feb., 20, 1997. Later that day Mr. Morgan

saw Mr. Walters standing next to his car. The routine of that winter day

wouldn't matter except that Leonard Walters and his wife, Lena, were

supposed to be dead. Missouri plans to execute Dannie Wolfe for

murdering the Camden county couple shortly before Mr. Walters and Mr.

Morgan were having coffee.

Despite the discrepancy, the Missouri Supreme Court

recently affirmed Wolfe's death sentence. Judges Michael A. Wolff and

Ronnie White dissented, saying there was “substantial doubt” about

Wolfe's guilt.

The case has many of the telltale signs of the 13

wrongful convictions discovered in Illinois: no physical evidence,

police and prosecutorial irregularities, a self-interested witness and a

jail house snitch.The story began on Feb. 19 when Jessica Cox met Dannie

Wolfe during an evening of drinking and shooting pool at Lake Ozark.

Wolfe, a house painter, had a 20-year criminal record. Ms. Cox ended up

at Wolfe's motel. Ms. Cox's fiance testified she called him at 7 a.m. He

checked the time on his caller ID. She said she had been kidnapped, was

at the hospital for tests and that the kidnapper had been arrested. By

Saturday night the fiance and most of the town had figured out the story

was false.

Ms. Cox admitted involvement in the Walters murder.

Through a lawyer, she made a deal to testify against Wolfe in return for

immunity. Suspiciously, police did not record her first statement and

erased another. At trial, Ms. Cox testified she and Wolfe had left the

motel around 4:30 a.m. and gone to the Walters' house to buy their

Cadillac.

On a test drive, Wolfe shot Walters in the head from

behind. Then Wolfe went into the house and murdered Mrs. Walters,

emerging from the house carrying a large safe.Ms. Cox's testimony has

holes. One is that Mr. Morgan saw Mr. Walters after he was supposed to

be dead. This suggests the murder actually occurred a day later, which

is more consistent with autopsy results.

Another inconsistency is Ms. Cox testified she called

her finance from the hospital around 9:30 a.m., two and on-half hours

after he got the call. Also, she had said in a pretrial statement that

“they” rather than he had carried the safe out of the house. That

pronoun takes on added significance because a roommate filed an

affidavit saying that Ms. Cox had told her that two men, Brian and Eric

had committed the murder. The roommate did not show up at trial and

Judge Mary A. Dickerson denied a recess to find her.

The judge also kept from jury important evidence

impeaching Ms. Cox. As a girl, she had filed two false police complaints,

claiming to have been kidnapped and raped. The other witness against

Wolfe was a jail house informant who cut a deal. The prosecution

violated court rules by failing for six months to disclose the informant

as a witness. When the defense found out, it was discovered another

prisoner who said a man named “Terry” had robbed the Walters. Terry and

Ms. Cox were seen together around the time of the murders. But the judge

excluded mention of Terry.