He was found guilty of three counts of manslaughter on June 21, 2005, the forty-first anniversary of the crime. He appealed the verdict, but his punishment of 3 times 20 years in prison was upheld on January 12, 2007 by the Mississippi Supreme Court.

Biography

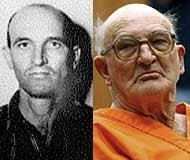

Killen was a sawmill operator and part-time Baptist minister and also a kleagle, or klavern recruiter and organizer, for the Neshoba and Lauderdale County chapters of the Ku Klux Klan.

Murders

During the "Freedom Summer" of 1964, two Jewish New Yorkers, Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, and one black Mississippian, James Chaney, 21, were murdered in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The Ku Klux Klan organizer Edgar Ray Killen, along with Cecil Price (then deputy sheriff of Neshoba County), had gathered a group of men who hunted down and killed the three civil rights workers. The Mississippi Civil Rights Workers Murders galvanized the nation and helped bring about the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The killings are the basis of the 1988 movie Mississippi Burning.

At the time of the killings, the state of Mississippi made little effort to prosecute the perpetrators. The FBI, under the pro-civil-rights President Lyndon Johnson and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, directed a vigorous investigation.

Federal prosecutor John Doar, circumventing dismissals by federal judges, opened a grand jury in December 1964. Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall appeared before the Supreme Court to defend the federal government's authority in bringing charges in November 1965. Eighteen men, including Killen, were arrested and charged with conspiracy to violate the victims' civil rights in U.S. v. Cecil Price et. al..

The 1967 trial in federal court before an all-white jury convicted seven conspirators and acquitted eight others. For three men, including Killen, the trial ended in a hung jury, after the jurors deadlocked 11-1 in favor of conviction. The lone holdout saying she could never convict a preacher. The prosecution decided not to retry Killen and he was set free. None of the men found guilty served more than six years.

Journalist Jerry Mitchell, an award-winning investigative reporter for the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, had written extensively about the case for many years. Mitchell had already earned fame for helping secure convictions in several other high profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the assassination of Medgar Evers, the Birmingham Church Bombing, and the murder of Vernon Dahmer.

For the murders of the civil rights workers, Mitchell developed new evidence, found new witnesses, and pressured the State to take action. Working with Mitchell were high school teacher Barry Bradford and a team of three students from Illinois.

They got Killen to do his only taped interview (to that point) talking about the crime. That tape showed Killen clinging to his segregationist views and clearly competent and aware. The students uncovered potential new witnesses, created a web site, lobbied Congress, and focused national media attention on the reopening of the case. Ben Chaney called them "Superhero Girls".

Re-emergence of the case

In 2004, Killen declared that he would attend a petition-drive in his behalf, scheduled by the Nationalist Movement at the 2004 Mississippi Annual State Fair in Jackson, Mississippi. It opposed Communism, integration and non-speedy trials. The Hinds County sheriff, Malcolm MacMillan, conducted a counter-petition, calling for re-opening of the case against Killen.

Killen was arrested for three counts of murder on January 6, 2005. He was freed on bond shortly thereafter. His case drew comparisons to that of Byron De La Beckwith, who was charged with the killing of Medgar Evers in 1963 and arrested in 1994.

Killen's trial was scheduled for April 18, 2005. It was deferred, however, after the 80-year-old Killen broke both of his legs chopping down lumber in his rural home in Neshoba County. The trial began on June 13, 2005, with Killen attending in a wheelchair. He was found guilty on June 21, 2005 of manslaughter, 41 years to the day after his crime.

The jury of nine whites and three blacks rejected the charges of murder but found him guilty of recruiting the mob that carried out the killings. He was sentenced on June 23, 2005 by Circuit Judge Marcus Gordon to the maximum sentence of 60 years in prison, 20 years for each manslaughter, to be served consecutively. He will be eligible for parole after serving at least 20 years, although it is almost impossible he will live this long given his age and health.

At the sentencing, Judge Gordon stated that each life lost was valuable and strongly asserted that the law made no distinction of age for the crime and that the maximum sentence should be imposed regardless of Killen's age.

On August 12, Killen was released from prison on a $600,000 appeal bond. He claimed that he could no longer use his right hand (he had to use his left hand to place his right one on the Bible during his swearing-in) and was permanently confined to his wheelchair. Gordon said he was convinced by testimony that Killen was neither a flight risk nor danger to the community. However, on September 3, the Clarion-Ledger reported that a deputy sheriff saw Killen walking around "with no problem".

At a hearing on September 9, several other deputies testified to seeing Killen driving in various locations. One deputy said that Killen shook hands with him using his right hand. Gordon revoked the bond and ordered Killen back to prison, saying that he believed Killen committed a fraud upon the court.

On March 29, 2006, Killen was moved from his prison cell to a Jackson, Mississippi hospital to treat complications from the severe leg injury he sustained in a logging accident in 2005.

Former Klansman found guilty of manslaughter

Conviction coincides with 41st anniversary of civil rights killings

CNN.com - Wednesday, June 22, 2005

PHILADELPHIA, Mississippi (CNN) -- Forty-one years to the day after three civil rights workers were ambushed and killed by a Ku Klux Klan mob, a jury found former Klansman Edgar Ray Killen guilty on three counts of manslaughter Tuesday.

The 1964 "Freedom Summer" killings of James Chaney, 21, Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, helped galvanize the civil rights movement that led to major reforms in access to voting, education and public accommodations.

Circuit Court Judge Marcus Gordon set Killen's sentencing for Thursday at 10 a.m. (11 a.m. ET). He faces a prison sentence ranging from one to 20 years per count, said Mississippi Attorney General James Hood.

"There's justice for all in Mississippi," Hood said.

The jury of nine whites and three blacks reached the decision after several hours of deliberations. The conviction was on a lesser charge; prosecutors had charged Killen with murder.

Killen, 80, displayed no emotion as the verdicts were read.

But as the wheelchair-bound man was being escorted from the courthouse under heavy guard, he took swipes at reporters' microphones and cameras. One of the reporters was black, as was a cameraman.

'This is not over with'

Chaney's brother, Ben, said that despite the verdicts, "This is not over with. ... But we'll take what we got."

From her home in New York's Manhattan, Goodman's mother, Carolyn Goodman, 89, said she had waited a long time for a guilty verdict, but it was "nothing to be happy about."

"I'm just overcome. ... But you know I had a feeling it was going to happen," she said.

"I just hope he's off the streets," she said of Killen. "I don't want anything more terrible than that. I don't want anything violent. I'm against capital punishment."

Schwerner's widow, Rita Bender, said, "I would hope that this case is just the beginning and not the end."

She acknowledged the fact that the case likely became a high-profile one because Schwerner and Goodman were white New Yorkers who came to the South the summer of 1964 with hundreds of other volunteers to register black voters. Chaney was a black man from Mississippi.

Neshoba County District Attorney Mark Duncan said the verdict means his county will no longer "be known by a Hollywood movie anymore," referring to the 1988 film "Mississippi Burning" based on the killings.

"Today we've shown the rest of the world the true character of the people of Neshoba County," Duncan told reporters.

Prosecutor: 'Venom' still exists

In his closing argument Monday, Duncan implored the 12 jurors to "hold the defendant responsible for what he did."

"What you do today when you go into that jury room is going to echo throughout the history of Neshoba County from now on," Duncan said. "You can either change the history that Edgar Ray Killen and the Klan wrote for us, or you can confirm it."

"Find him guilty of murder," Duncan said. "That's the verdict that the state of Mississippi asks you to return."

"Those three boys and their families were robbed of all the things that Edgar Ray Killen has been able to enjoy for the last 41 years. And the cause of it, the main instigator of it was Edgar Ray Killen and no one else," the district attorney said.

"He was the man who led these murders. He is the man who set the plan in motion. He is the man who recruited the people to carry out the plan. He is the man who directed those men into what to do."

The balding, bespectacled Killen -- a former part-time Baptist preacher -- appeared to be sleeping during much of the closing remarks.

Hood, who led the case, said he wished "some of my predecessors would have done their duty" by bringing charges against Killen. Noting that it was "not good politics to bring this case up," he said, politics and time should not get in the way of justice.

Hood said testimony showed Killen possessed "venom" at the time of the killings and still does.

"That venom is sitting right there. It is seething behind those glasses," he said. "That coward wants to hide behind this thing and put pressure on you."

Burden of proof

Defense attorney Mitch Moran said "nothing in the record shows Edgar was there" during the ambush and killings.

"The '60s was a terrible era in a lot of ways. We do not need to relive them, and we do need to go forward," Moran said. "What I'm asking you to do is to look at this evidence and hold the state to the burden of proving this case beyond a reasonable doubt."

On June 21, 1964, Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were on their way to investigate the burning of a black church when they were briefly taken into custody for speeding.

According to testimony, the Klan had burned the church to lure the three men back to Neshoba County.

After they were released from the county jail in Philadelphia, a KKK mob tailed their car, forced if off the road, and shot them to death. Their bodies were found 44 days later buried in an earthen dam -- in a trench dug in anticipation of the killings, according to testimony.

In a 1967 federal trial, an all-white jury deadlocked 11-1 in favor of convicting Killen. The lone holdout said she could not vote to convict a preacher.

Seven other men were convicted of conspiring to violate the civil rights of the victims, namely their right to live. None served more than six years in prison. At the time, no federal murder statutes existed, and the state never brought charges.